notes to the Ideal City: pt ii

...the marginal monstrosities...

I have elsewhere called us Cyclopes, or compressed sea creatures; but our monstrosity is perfectly real.

It is, I sometimes think, a tidal phenomenon: twice daily we are forced to confront the wreck of ourselves at some low tide of being, once in the morning and once in the evening, staring into mirrors, studying and prodding and testing the collapse of our body.

Twice daily then, when I brush my teeth, I spit blood. My teeth are falling out.

—wreck of ourselves—

I went to the dentist for the last time a few days before I quit my job; this itself was my first visit for ten years. The dentist, an agreeable quietly spoken man, talked me through the accumulated dints and degradations of a decade. The account could well have been worse. My teeth, he explained, were in passable condition, but there was such caked scaling that a series of clean-ups was scheduled. But here was the turning point of his argument: while bone damage in much of the body can be repaired, bone damage at the root of the tooth cannot. It is a ligament joint, and any degradation is irreversible. I had sustained a certain amount of such damage, which explained my bleeding gums, and all I could hope now would be to slow any further deterioration.

The hope was a false one; it was akin to saying, if you eat right and don’t smoke perhaps you will die of something other than cancer before cancer kills you. I had the opposite of cancer: a refusal of the material of my teeth to replicate. But it amounted to the same thing. Perhaps you will die of something before your teeth fall out, before you are a mumbling wreck. Perhaps, with work and injections and a coal chisel we can flatline your decline for you a little. You’ll be able to forget about your death for a while, it will, in the best cases, seem, locally, to recede; you will occupy grottos in the garden of life, you will smile, with your teeth, upon the sunlit garden of your soul. But you know in your heart, you will still be sitting here grinning like a toothless fool when winter is upon you.

I did not go back to the dentist, not because I didn’t want him to scrape my teeth, but because I needed to economise strictly once I had quit my job; I foresaw a few brief years of life, in which I would always have sufficient teeth. I would keep a fund against the emergencies of acute pain, but forgo immortal enamel.

![]()

By rhetorical in this case I simply mean that in the cinquecento you are not merely enticed by a garden or indulged by it, you are in some measure controlled by it, or seduced by it, by its inventiveness, its elaborate disposition of elements.

Epideictic is one of the three classes of rhetorical display identified by Cicero, of which the others are forensic (proper to a Court of Law) and deliberative (proper to the Senate). Epideictic is a catch-all category which includes addresses at funerals or celebrations, speeches giving praise or blame.

A garden is an exercise in epideictic rhetoric insofar as it displays the consciousness of one man—its patron or owner, not its designer. In the garden we see this man laid out, see his intellectual and sentimental resource articulated, given rein, the potentiality of his city or kingdom realised, the balance of copiousness and order made good.

Rhetoric also implies a degree of remove from the direct experience, a remove that allows us to perceive order in the sensuous experience, a structure that can be read.

Why gardeners no longer conceive of their work as an exercise in epideictic rhetoric, I cannot say.

![]()

This is a generalisation. The quattrocento knew perfectly well how to move individuals around in space. Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, for instance, binds the experience of a garden to the hermetic logic of a narrative arc, an unveiling of mysteries as the narrator moves towards the centre, a sort of bucolic and empty-headed Dante in search of his Beatrice.

Less fancifully, the High Renaissance or Mannerist Rhetorical garden can be said not only to find antecedents in the quattrocento, but to locate its origin at the court of Ferrara in the 1470s, where Borso d’Este and his successor Ercole used the remnant earth of a new rampart to construct an artificial mount, which was planted with a boschetto and studded with fountains and pavilions and statues; in the adjoining formal gardens there were grottoes. Ercole also, somewhat later, planted a small lozenge-shaped island in the Po in the same wild manner; this garden was approached through a complex of buildings where, in the forecourt, stood a fountain representing a tree; its trunk was of brass, and jets of water formed the branches.

It was Ercole d’Este’s grandson, Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, who was responsible for the Villa d’Este at Tivoli, and also for converting the vineyards of his cardinalatial residence (Palazzo Quirinale) into a boschetto, notable in its day for its number of statue groups and grottoes. The d’Este connection, in other words, seems to have been a conduit through which the extravagant Ferrarese (quattrocento) manner was imported into cinquecento Rome.

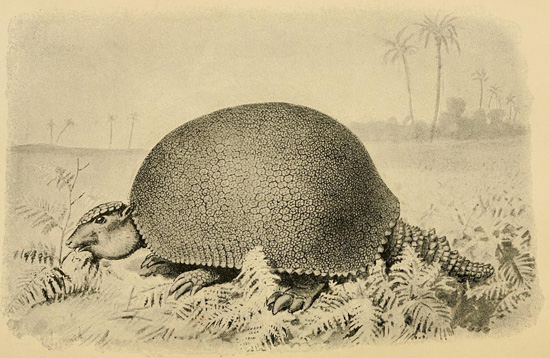

It amuses me to note that Ippolito’s uncle, also Ippolito d’Este, also a prelate (archbishop of Estergom, Milan, Ferrara) died in 1519 of an indigestion of lobster. I wonder if he thought to remove the exoskeleton.

![]()

In the allotments it is mostly pests of one sort or another that I fear; but in the Kelley garden I am coming to abhor dandelions, which Kelley—perhaps for want of something to say—has instructed me to purge from his various patches of grass and flower beds.

I find that in the iterative process of stooping, picking, uprooting, casting aside, you become simultaneously battle-hardened—your technique is grooved, your attention hyper-focussed—but also weary of the low down horror of life at a few inches from the soil, your face constantly in all this crawlspace; dandelions start by annoying you but end by making you queasy; they defeat you by their dumb persistence, the alien tentacular form they take, the rapidity of their growth and change, their spidery stealth; you almost want to let them go, let them take over, reclaim the pavements, the paths, sprout from your nose, your mouth, draw sustenance from your own dusty bones.

—sprout from your nose—

I know too that at some point soon I will have to pick slugs, snails, caterpillars off the back of cabbage leaves in my allotment. I am beginning to realise that a gardener does not lay down and police boundaries. I am not a pilgrim pushing back the virgin forest so that I can plant and sow my other, cleaner, functioning rows of vegetables, my pure and numerable monoculture; rather, I am forced to draw on all this welter of disorder, of writhing crawling growing matter; my little field of corn—or my hundred of beans and potatoes—is no more than a version of it.

I look at Monty Don turning over the soil in his vegetable patch, and I do not recognise it as soil; it is loamy, fluffy, mobile, rich; there is not a stone or a root in it; when I dig, the earth is recalcitrant, claggy, globulous, compacted; full of wormy crawling things; I do not want to touch it; Monty Don’s soil is otherworldly, it is the soil of the paradisus terrestris, the soil of a rich man.

I crave the clarity of my room, where the flies and mosquitoes and wasps bounce of the windows that I keep shut, where the green stuff is all outside. Where I sit in a sealed environment of inert and beneficent plastics (paradoxically characterised by nothing so disturbing as plasticity) and metals, perhaps some well seasoned wood from which all life has been healthfully expunged; if I died here in my chair and rotted to nothing the room would look much the same a thousand years hence, a little dustier perhaps, but not much different. The allotment, on the other hand, would by then have elaborated its own monstrous logic, would have become the wildwood, stalked by monsters, green men.

![]()

In summarising the various interpretive schemes, Lynette M. F. Bosch notes (in "Bomarzo: A study in personal imagery" (Garden History, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Autumn, 1982), pp. 97-107)) that ‘No interpretation has yet provided a single source for the garden's images.’ She is modest enough to make no such attempt herself.

Suggestions have focussed on literary allusion and memento mori, whereby the boschetto becomes either a humanist play of wit or a funerary park erected in memory of his wife.

It has also been suggested (by Lynette, in fact, but only on behalf of three of the garden objects) that the organising principle is autobiographical (referencing, for example, his incarceration after the battle of Hesdin and the fidelity of his wife in that period (case pendente) and his jealous rage following the elopement of his mistress, Laura, in July 1574, (giant dismembering shepherd boy).

According to this last hypothesis, the garden is a region of imprese or emblems. This is a murky but plausible thought; the old Duke decking his wood like a Bluebeard's hall of the memory and imagination. Two of Orsini’s literary circle in Bomarzo in these years were Giovanni Ruscelli and Ludovico Domenichi editors of two of the most influential emblems books of the sixteenth century (Le imprese illustri con ispositioni et discorsi, Venice, 1556 and L'imprese d'arme et d'amore, Venice 1562).

Regardless of the specifics, the garden seems to want to be read like a book of emblems: in or out of sequence, in a progress either logical or surprising. For the initiate (Orsini, perhaps his visitors) this approximates to a meditative excursion that must have at least felt like a gnosis; for the non-initiate (Orsini's peasants, us) it is like being left alone for an hour in the house of a stranger.

Orsini was a dilettante antiquarian and had family lands up near Sovano, where in the sixteenth century there were extant examples of Etruscan gabled aedicule tombs. One of the objects in the Sacro Bosco has been read as a mock ruin of just such an edifice. Northern Lazio was an Etruscan heartland, and suggestions have been made not just of an antiquarian’s Etruscomania, but of a cultural persistence, some monstrous Etruscan effluent permeating the land and erupting here at Bomarzo.

![]()

The gardens were reclaimed after World War II; not so much saved as neutralised, turned into a theme park. There are no monsters in the woods any more, we seem to say. We got all that out of our system at Nuremberg.

Our monsters bind us in time and place. In Star Trek: The Next Generation they are never called monsters, they are always entities, lifeforms. But when, for example, Picard is forced to fight an, ahem, ‘entity’ on El-Adrel and, on the eve of the final battle he tells Dathon, his gibbering compadre, the story of Gilgamesh and Enkidu fighting the Bull of Heaven, he locates himself securely in a mythic space, a space where monsters roam beyond the ring of firelight, where their menace binds us together within that ring.

—Gilgamesh was a King at Uruk...—

The ‘entity’ he encounters is a monstrous form, the beast of El’Adrel, a minotaur, a Cyclops.

—'entity'—

And in the same way, within our own memory, out beyond Norbiton, in the Marches, the wild lands, there was Gordon Brown. We had heard rumour of him from over the horizon: glimpsed the thunder-browed Cyclops, stomping joyless around his subjugated domain, brutal, gormless, misunderstood. Until, in early May, in good time both for the crops and the financial year, those fey Olympians Clegg, Cameron and Osborne dug the old Titan from his lair, bound and castrated him, and cast him into the outer dark.

Digging in my allotment, the news of these events was like the news of the Light Brigade at Balaclava to a serf out on the steppes, stooping over his patch of vegetables: garbled, delayed, lacking in detail, irrelevant, mythical, dreamlike; probably untrue.

![]()

Mrs Isobel Easter, I discover, has not a room but a small system of interconnected rooms on the first floor of the house, of which on this occasion I see one, the defining character of which is encrustation.

It is a reasonably large room, but the proliferation of small objects on shelves, surfaces, and in drawers (I noticed as she rummages for her curiosity) extend its surface area to infinity. This, I take it, is what happens if you stay still for long enough. The objects themselves are unremarkable, and are immediately available to a rough and ready taxonomy:

- Books, papers, and correspondence, bundled, stacked and loose

- bits of stick, shell, stone, feather (found objects? Natural history?) including five very large beetles (Javanese, Indian, South American) pinned and labelled in plastic display cases

- small statuettes and otherwise representational ornaments (a bull, what looks like a lama or alpaca, a Mercury)

- some loose jewellery, beads

- decorative boxes, various (inlaid, lacquered, fabric-lined, fabric-covered, including one ottoman-like bench)

- stationery, including tools (multitool, stapler, a lot of paper clips)

- postcards in frames and other two-dimensional representations (drawings, photographs)

A room, then, of barbaric untidiness, or at any rate of dishevelled copiousness of spirit. I think of it, henceforth, as the Grotto.

![]()

Behind me, Isobel has excavated her curiosity and is now unpacking it from boxes and tissue paper for my inspection.

It is an Etruscan lamp.

—curiosity—

I learn later, from Clarke, the rumour that Hunter Sidney once stole just such a lamp from an unlocked cabinet in the museum of the Villa Giulia in Rome, where he had chased Mrs Isobel Easter (to Rome, not the Villa Giulia: quite another story which I will not attempt to retell here).

I suppose this to be the lamp in question.

![]()

This is something I read somewhere. Perhaps in Terry Comito's book, The Idea of the Garden in the Renaissance, or perhaps somewhere else. Where it comes to proper citation, I increasingly feel like an ill-mannered barbarian horde on the move. Who cares who said it? I'm saying it now. It may in fact be that one of the points of proper citation is not to show the debts you owe, but to dissociate yourself from someone else's particular mode of insanity. Perhaps that's what I'm doing here.

![]()

...a gastronomy of scrag ends...

A speciality of mine. My economic circumstances do not allow me to eat particularly well.

I live for the most part now on pasta and tomatoes, toast, tea, and occasional cheap vegetables. But in spite of my parsimony in matters of gastronomy, or perhaps because of it, I am not feeling well. I sag, I bloat; I am a pasty, a slug.

—a pasty, a slug—

Clarke tells how once, when he was living in Rome with no money for rent let alone food, he broke out in acne for the first time since he was fifteen.

He went round to see his ex-girlfriend and she laughed. But the next day she appeared at his door with a cardboard box in which she had packaged an emergency food drop: fresh vegetables, bags of pasta, tins of tomatoes, sausages, potatoes, fresh fruit, tobacco, bottle of wine. A box of ingredients, he says, with some bitterness. The last meal of a condemned man reimagined as a celebrity chef's trip to Borough Market.

![]()

...Restaurants are the bourgeois ideal of a convivial space...

Restaurants emerged in the middle of the eighteenth century. Before that there were plenty of places you could get a meal, but not where the food was the centre of the experience, and not where you sat cheek by jowl with strangers who were ostensibly your equals (it is the same menu, the same prices for everyone) but where in fact there were many pleasingly subtle gradations of status – a good table, more obsequious service, and wines more prestigious by several orders of magnitude. And the menu posted outside the door is as much a barrier or a warning as an advertisement.

Priscilla P. Clark supplements this observation (in "Thoughts for Food I: French Cuisine and French Culture"—The French Review Vol. 49 No. 1 Oct. 1975 p. 37): 'While the restaurant grew out of the earlier forms [cabarets, cafes, inns, tables d’hôte and caterers (traiteurs)], it offered more choice, a more systematic presentation (menus) and, most important, undivided concentration on the meal as a harmonious entity... the restaurant was an urban, and more specifically a Parisian phenomenon.’

![]()

...inconsistent with conviviality, properly understood...

Eating together in comfortable silence might not be an obvious form of conviviality, but if we accept, as we must, that good talk is predicated upon good and contemplative silence then it follows that it is a valid one. The convivium extends beyond any given meal.

I think we could go further with this idea and consider the properties of a solitary conviviality.

—properties of a solitary convivium—

– St. Paul the Hermit Fed by a Raven

after Guercino

I shared a flat for a few months with a man in Venice who was divorced, and employed from time to time on the transport boats; otherwise he was a musician. He had his hair cut with quiff and sideburns like an Elvis-impersonator; but unlike Elvis, I suppose, every day at lunchtime he would prepare himself a bowl of pasta or rice or whatever, and he would lay the table in his living room as though he were in a trattoria—knife and fork, bread basket, carafe of water, cruet set, napkin in a ring. And then he would sit down by himself at the table in silence for twenty minutes and studiously munch his way through his repast.

He said that the meal should be a moment of pause and reflection in your day.

The logical extension of my argument would be that conviviality is a virtue fostered as well or better in solitude than in company. The hermit, or Venetian Elvis, is in that moment of quiet absorption, a fully convivial being.

Convivial with what, is another question entirely.

![]()

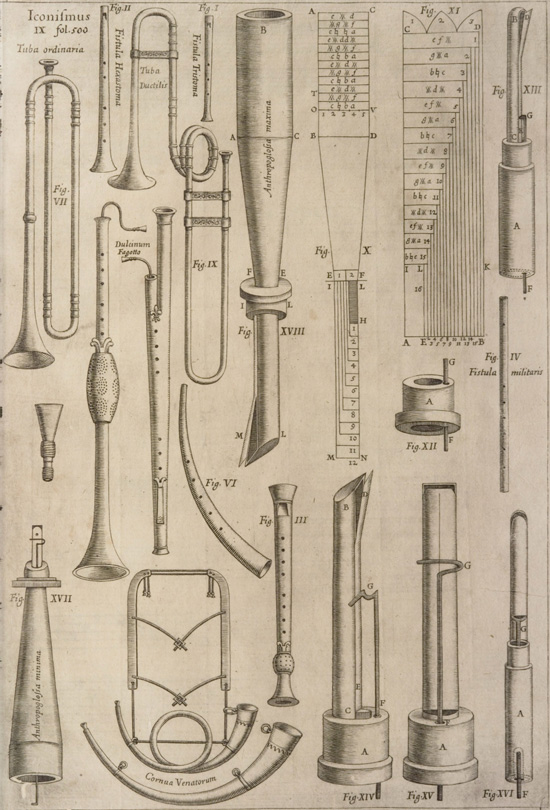

...hand on lyre...

The instrument is a Renaissance lira da braccio rather than a classical lyre. It is not easy to see here, as it appears to disappear up Priapus's skirts, but Bellini painted an angel playing one on the San Zaccaria alterpiece of 1505.

—now defunct—

– Pala di San Zaccaria

Giovanni Bellini

The lira da braccio, with its two drone strings (bourdons), belongs to a now-defunct evolutionary branch of stringed instruments, pushed from their niche, I suppose, by the more muscular, more Neanderthal viols, which in their turn were superseded by the hyper-intelligent violin family.

Attending a concert of Renaissance music is much like visiting the Natural History Museum.

—Natural History Museum—

Your eye wanders over the stage, spotting the extinct grotesques, the parping, flapping, cumbrous curiosities, and you try in vain to name them: Sackbut? Theorbo? Oboe da caccia? Basset Pommer? Tromba marina? Hurdy-Gurdy?—as you might, in a museum of bones, try to pick out the auroch or the glyptodon.

—Basset Pommer?—

![]()

...pricks of lusts and snorting asses...

I would be pleased to think it, but ultimately the picture is too strange to postulate an inner convivium. There is something disconcerting about those watchful or indifferent gods, after all, that excites, in the wrong mood, horror. What Priapus does, it seems, is his affair. The only being who will be woken by the braying is Lotis. Mercury and Proserpine in particular are dream-like watchers of the rape of their sister (perhaps a naiad is too inconsequential a being for them to care). And both Proserpine and Mercury, and indeed all of the gods, are acquainted with rape first hand, one way or another.

Or perhaps, in fact, it is that very dream-like state of indifference or inaction—they show not even amusement at what is passing, although we are assured by Ovid that the braying of the ass was accompanied by gales of laughter—which suggests the assembly of inner spirits in the first place.

![]()

...like the feasts T.E. Lawrence describes.

I am thinking of the great communal meals which Lawrence attended from time to time, in Feisal's tent and elsewhere: "... cubes of boiled mutton were sorted through the great tray of rice, Medfa el Suhur, the mainstay of appetite."—page 128 in my Jonathan Cape edition of 1973.

But glancing back through the book, it is by the frugality, necessarily of the campaign in the desert in general and particularly of Feisal himself, that I am struck.

'Feisal', writes Lawrence, 'was an inordinate smoker, but a very light eater, and he used to make-believe with his fingers or a spoon among the beans, lentils, spinach, rice, and sweet cakes till he judged that we had had enough, when at a wave of his hand the tray would disappear, as other slaves walked forward to pour water for our fingers at the tent door. Fat men, like Mohammed Ibn Shefia, made a comic grievance of the Emir's quick and delicate meals, and would have food of their own prepared for them when they came away.' (p. 127).

In part, fat men notwithstanding, Feisal was typical of the Beduin, as Lawrence understood them:

'The Beduin of the desert, born and grown up in it, had embraced with all his soul this nakedness too harsh for volunteers, for the reason, felt but inarticulate [except that Lawrence will articulate it for him], that there he found himself indubitably free. ... In his life he had airs and winds, sun and light, open spaces and a great emptiness. There was no human effort, no fecundity in Nature: just the heaven above and the unspotted earth beneath.' (p. 38)

It is perhaps apt that I should find myself writing about frugality in the context of our feast, for a feast is only so by dint of its asymmetrical relation to the rest of life. Every day is potentially a feast day in the Ideal City but few are actually so. When I left the New Devi I did not step into deserts of heaven and unspotted earth exactly, but I was aware of leaving a place of plenty for a more precarious and pitted existence.

![]()

In 1397, Palla Strozzi was given a copy of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia Uphegesis by Emmanuel Chrysoloras. The first latin translation by Giacomo de Scarperia followed in 1406, and it was first printed in 1477, being the first of the incunabula with engraved illustrations.

Ptolemy described the difference between geography and chorography as follows:

Geography is the representation, by a map, of the portion of the earth known to us, together with its general features. Geography differs from chorography in that chorography concerns itself exclusively with particular regions and describes each separately, representing practically everything of the lands in question, even the smallest details.... It is the task of geography on the other hand, to present the known world as one and continuous, to describe its nature and position, and to include only those things that would be contained in more comprehensive and general descriptions .... Again, chorography deals, for the most part, with the nature rather than with the size of the lands. It has regard everywhere for securing a likeness but not, to the same extent, for determining relative positions. Geography, on the other hand, is concerned with quantitative rather than with qualitative matters, since it has regard in every case for the correct proportion of distances, but only in the case of the more general features does it concern itself with securing a likeness, and then only with respect to configuration."1

There is here a clear intimation that the shift in scale necessitated also an alteration of method, approach, understanding: geography assumes a homogenous and infinite, in the sense of boundless, lump of matter called the Earth upon which various unvarying natural processes are inscribed; while chorography tilts at an exhaustion of detail within an arbitrarily bounded space, generalising no processes.

And I would go further and argue, or anyway state, that the natural province of (Renaissance) chorography is the city and its environs, whereas the natural province of geography is the totality of the earth, and while, in theory, there is no reason why the reverse could not be the case (so that cities were treated as geographical processes or the result of those processes, and the earth as an arbitrarily bounded and wholly particularised locale), nevertheless the processes and understandings which access the one are not usually appropriate to the other. The City and the Earth, geographically speaking, are radically discontinuous entities – not least, because to suppose otherwise would be to postulate a greater, overarching episteme within which geography, chorography and topography would all operate at their varying scales—a manifest nonsense.

Such at least is my cursory understanding of Ptolemy.

![]()

Sir John Mandeville’s account of his travels in the East were more popular even than those of Marco Polo in the late Middle Ages.

The travels tell of a journey to the midpoint of the world—Jerusalem—and beyond, to Trebizond, the Indies, the Malay archipelago and China. Unlike Marco Polo, whose travelling eye focuses for the most part on commercial possibility, Mandeville mostly relates fantastical wonders—the familiar line-up of monopods, men with eyes in their shoulders, dog-faced men, and so on.

—monopod—

– "Heures à l'usage des Antonins"

Maître du Prince de Piémont (attr.)

The fictional Sir John, like his empirically real contemporaries, inhabited a world which struggled in its own way to reconcile the geography of the known world with biblical, classical and Arabic sources.

Columbus was as familiar with Mandeville as he was with Marco Polo, and carried a copy with him on his voyage West. However, it should be admitted that Mandeville was never going to be much help had Columbus in fact arrived at the lands of the Great Khan, no more than the Anatomy would be if you, reader, pitched up in Empirically Real Norbiton.

![]()

Practically, if not etymologically, the voyages of the Starship Enterprise are geographical in nature. They are explorations, mappings, studies of astral ecosystems, alien social structures, anomalies, entities; the charting of class M planets like so many bays, harbours and ports.

Accordingly, episodes of Star Trek often start with a glimpse of a structured, grid-like mission with which the crew is occupied, as for instance these examples from The Next Generation:

-

• “Captain’s log, stardate 43957.2: We are charting an unexplored star system within the Zeta Gelis cluster.” Transformations or

• “Captain’s log, stardate 42779.1: We are en route to the epsilon 9 sector for an astronomical survey of a new pulsar cluster." Samaritan Snare

The context of each episode, we are given to understand, is one of routine scientific enquiry. The Federation, like the Borg (see Cartographical), seeks to throw a comprehensive grid over a homogenised space, and attend to the details subsequently, and methodically.

Needless to say, from this characterless routine an adventure is in each case quickly precipitated, a brisk encounter with an enemy, a danger, a wonder, a marvel. Were this a medieval chronicle we would be in the East with Sir John Mandeville, brushing up against cannibals, men with heads in their stomachs, tribes of idolaters; reporting on their improbable peculiarities (the Chandrans have a glacial mind and a three day ritual for saying hello), their social structure (Andorian weddings typically require the presence of four people), their potential for trade (the Tellarites have a long-standing trade dispute with the Andorians). Picard at the Klingon High Council might be Marco Polo at the Court of the Great Khan, a trusted emissary inserted somehow in the interstices of the affairs of Empire.

But then, there are also Columbus-like ruptures in geographical space, as when for example the entity known as Q transports the Enterprise to their first encounter with the Borg. Suddenly (and neither for the first nor last time) the explorers find themselves in turn explored, and threatened with exploitation by a dominant materialist culture:

The unstated missionary zeal of the Federation, their faith in the radiant and self-evident qualities of ‘humanity’, questioned only to confirm its power, is perhaps just another, albeit gentler, version of the insane malice of the conquistadors, or more precisely of the Jesuits and Dominicans and Cistercians who followed the conquistadors.

The crew and captain of the Enterprise makes up its moral order as it goes along; it has its Prime Directive, but the exigencies both of galactic exploration and swift narrative turnover make that moot. Picard has constantly to invent his moral world in the face of men with heads in the stomachs, just as Cortés invented his rituals of appropriation.

Exploration, in other words, not only gives the galaxy a chorographical and anecdotal shape, but demands from time to time wholesale readjustment, redistribution, a systematic openness.

![]()

Her full name, preposterously for an Irishwoman, is Veronica de Viggiani—she had been married to an Italian from whom she was now separated, but whose name she retained for the present. Her use of the name Monica stemmed from her own childish mispronunciation.

The name Veronica—later falsely etymologised as the vera icon, the true image—is associated with the sudarium, the cloth with which Saint Veronica wiped the brow of Christ on his road to Calvary and which subsequently retained the image of his face.

—retained the image—

– Veronica Holding the Sudarium

Hans Memling

Coincidentally, Veronica (de Viggiani, not the Saint) strongly reminded me of the woman I had been in love with in Italy, mostly, I surmised at the time, because of the colour and cut of her hair (black and shortish) and the size of her nose (small). I subsequently realised, however, that I had surmised incorrectly, since it was really a gestural characteristic which was common to both women: an oblique, alert, perhaps slightly furtive way of looking at you when she—they—thought you were not looking. Since this was of necessity a peripheral perception on my part, it took me some time to learn to filter for it.

It was for this reason—the resemblance—that I chose and choose to call her Veronica in spite of her mild opposition.

![]()

The story of her nativity, so far as I could establish it at this point, was that Kelley had abandoned her pregnant mother in Ireland when he ran to California. That would make Veronica about forty years old, or so, in the summer of Hunter Sidney’s death.

Hunter Sidney and Veronica had struck up a working acquaintance (his description) around the time of his involvement with and estrangement from Kelley’s wife. He says that, whatever the mechanics of their introduction, it had been a sense that the lives of both were peripheral to someone else’s more potent drama that had united them, in dudgeon as it were.

![]()

This admittedly dismal meditation was set in train by my discovery of Veronica de Viggiani in Hunter Sidney’s garden. Not for the first time, I became aware of groupings or histories in the people I knew as fellow citizens—Hunter Sidney, Kelley, his wife, Tony dell’Aquila—which threatened the disjoint integrity, if I can call it that, of the Ideal City itself. I don’t go so far as to call it a faction, a cabal, a conspiracy—if it were I could at least hope to expose it, extirpate it, stamp it out—but it was evidence, at least, of an underlying topography invisible to the daily eye yet shaping every footfall.

In short, where the Norbiton side of the equation in Norbiton: Ideal City was concerned, I was conscious of standing outside that which I had created or helped to create.

However, this conclusion led on, perhaps inconsequentially, (and perhaps not—I am no psychologist but I recognise the possibility of a connection) to the repeated sense of wonder in her presence, especially insofar as it was repeated regularly over the next days and weeks; akin, as I have said, to love or desire, but not love or desire. A sense of wonder which left me, like Columbus, with a futile desire to appropriate this new country or continent in ways that would not render it harmless, familiar.

Futile, because as Stephen Greenblatt remarks:

By itself a sense of the marvelous cannot confer title; on the contrary, it is associated with longing, and you long precisely for what you do not have. Columbus’s whole life is marked by a craving for something that continually eluded him, for the kingdom or the paradise or the Jerusalem that he could not reach, and his expressions of the marvelous, insofar as they articulate this craving, continue the medieval sense that wonder and secure temporal possession are mutually exclusive."

Marvelous Possessions p.81

![]()

It followed that the Ideal Fortification could only be built on a flat site, just as in designing the Ideal City you start necessarily with a blank sheet of paper, somewhere flat and characterless (neither too hot nor too cold, too damp nor too dry, says Alberti). There is no wresting with an existing topography or the complex pressures of context.

In the 1460s and 70s, the Sienese architect, Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1502), architect to Federigo da Montefeltro in Urbino and successor there to Luciano Laurana (c. 1420-1479), worked on a remote fortification, the castle of San Leo, perched on a sheer cliff above the drear and empty land of the Marche.

—drear land—

– Rocca di San Leo

– Photo: Edisonblus (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The fort had a reputation for impregnability, in part for its imposing stone works, but mostly for its unscalable perch. There was little an architect or engineer need do, except pile up the stones.

By 1494 Martini was in Naples, and present at the siege which would render San Leo and all other fortification in Italy suddenly irrelevant. When, in the 1490s he published his revised trattati d'architettura civile e militare (Codex Magliabechiano) he stated in book V, in which he dealt with fortification, that “the strength of the fortress depends upon the quality of its plan rather than the thickness of its walls”, an obvious and necessary but nonetheless revolutionary departure from all logic of fortification propounded hitherto. “The ancients”, Martini explains, “did not know our artillery”.

Martini, in proposing that henceforth the power of mind, not the accidents of geology or the piling up of stones, would determine the strength of fortifications, was setting the tenor of the coming century. It would be generally held (although not without contention) that the most perfect – functionally, the best – fortification was that which was built in the open, where the logic of geometry could be most completely brought to bear.

Hence Palmanova, you might say, lodged like an uplifted fossil in the centre of an empty plain, defending horizons of earth and sky from invisible armies, the rumour of the Turk, and, ultimately, nothing at all.

![]()

Emmet Lloyd tells me that his father in the 1980s did in fact build a bunker in their back garden. His nursery business had by then taken off, and Emmet thinks that the bunker may have been an index of insecurity, a compensatory or apotropaic gesture to the gods.

His father's imagination, he says, was certainly lurid enough for that: he was a big man and lame in one leg; he would go clumping over his nursery fields, spade in hand, bellowing incomprehension at his startled employees or pitching in with the work in terrifying bonhomie. Perhaps his vision of nuclear strike was bound up with his greenhouses, says Emmet; a nurseryman has constantly on the anxious fringes of his mind the possibility of damage to his greenhouses, as if the whole of his business were enclosed in a fragile glass case necessarily subject to attritional damage: the tenor of his business is an everlasting remedial fretfulness. Perhaps the old man woke at night in the sweat of dreams where mushroom clouds girded the horizon of his nursery, until in one more local flash the glass of his greenhouses passed through his flesh like a catrillion unleashed photons.

The bunker, says Emmet, is still there, derelict in a corner of the garden. And his father too, vast and durable, still lives in a corner of their house, clutching to the business like the ancient mariner to a spar of wreckage, mumbling his visionary shibboleths of gross profit, sunk costs, depreciation and amortisation.

![]()

In the decade following the advent of Charles VIII in Italy, Isabella d’Este (1474-1539) busied herself hollowing out the redundant medieval castle in Mantova into which she had moved on her marriage with Francesco II Gonzaga (in 1490), and creating in its rocky secluded interior a fair approximation of a Renaissance palazzo.

Isabella’s complex of rooms comprised a bed chamber, the studiolo proper, a private oratory, a large reception room (the camera degli armi) a library cabinet and a camerino da bagno. She was also close to the camera picta of Mantegna. And on the floor below the main suite of rooms was a grotto, a small room with a gilded stucco ceiling into which, it may be supposed, Isabella would from time to time, Erda-like, descend.

—descend—

– Grotto of Isabella d'Este at Mantova

A great prince, like a great Magus, discharges her power into talismans, synecdotes, emblems, and extends her empire over the realms of speaking objects; who knows but that there in that deep cave Isabella would mull, arrange and rearrange the most precious of her polysemous artefacts, seeking the correct arcane alignment, as though a syntactic energy of understanding might thus be released, fit matter for proper contemplation.

![]()

Mrs Isobel Easter was herself the instigator of the crime. She and Kelley had come to Rome for reasons that are not entirely clear to me and Hunter Sidney, desperate and abandoned, had followed them there. And his affair with Mrs Isobel Easter reached, in Rome, its greatest intensity.

At a certain point, Mrs Isobel Easter was visiting the Etruscan Museum of the Villa Giulia with Kelley, when, the two of them having drifted apart, she noticed, in among the silent cabinets, that one was open. She tells me that there was a centimetre of space where the glass front had not slid fully across, and, looking around at the entirely empty gallery, she laid the palm of her hand against it and tested it. It was not locked.

She says that she did not have the gall to open it more than an inch or two, but she took out some paper and sketched the two objects that she thought could be most easily reached—the lamp and a sort of votive statue on the shelf above. I have the drawing, given to me by Hunter Sidney.

—i have the paper—

That lunchtime she saw Hunter Sidney and showed him the drawings, described to him where the objects could be found, and suggested (laughing? trembling? imperious? coy?) that he steal one or both for her. He went to the museum immediately, found the room, the objects, the cabinet; slid it open as she had done, and stretched his hand inside. He says he would have stolen the statuette, given the choice, but it lay slightly beyond the lamp, and he was simply too nervous to have his hand inside for more fractions of a second than was necessary. He took the lamp and put it in his pocket.

He says it then took him a couple of sweaty minutes to realise that it was not like shoplifting, they would not wait until he tried to exit before they stopped him, there was nothing to be gained by hanging around, seeing if he was watched. So he left the museum and ran, he says, the length of the Villa Borghese until he could lose himself in some streets.

He had not seen Mrs Isobel Easter again in Rome. They had all returned to England, and she had ended the affair with him, he says, before he could give her or even tell her about the lamp, so in the end he posted it, well-wrapped, to her home address. And the lamp had disappeared, for him, down some funnel of silent time.

![]()

...first outlined by Alois Reigl and W.H. Goodyear in the 1890s...

Both were reacting to the prevailing explanation of ornamental devices as being based in craft technique—thus basket-weaving was said to generate weave patterns, and so on. But Reigl, taking his impetus from Goodyear’s more speculative work on the Lotus (The Grammar of Lotus, 1891), traced the development of a single motif through several millenia of European and Near Eastern art history.

According to Riegl's formulation, the acanthus—to take a significant example—is not a representation of the leaves of the acanthus plant, but a motif derived from the palmette. In other words, the acanthus ornament is an offshoot of the palmette, not a picture, so to speak, of an actual leaf. Riegl may have overstated his case somewhat (or indeed psychotically), but I am relieved to be able to remind myself of the fact that plants in ornamental borders do not necessarily have anything to do with plants that actually grow. Perhaps this should have been obvious to me all along. Plants inhabit a different world from painted representations of plants, not only ontologically, but epistemologically, perceptually. You can dispense with the one in a consideration of the other. Art history suddenly becomes an impersonal, depeopled, and above all clean vision of applied pigment, chipped stone.

![]()

...through the World in its entirety...

This is what I thought then, and I think, now, secretly, indulgently, from my retirement, that I wasn’t so far off the mark.

But rather than emphasising the ornamental nature of the figures in Italian Renaissance art, it would have been more accurate, more taxonomically fitting, to return the ornament to the margins. To accord to the margins their own strange life. This was, after all, the initiatory impulse.

It is a truism to remark that the borders of anything—a painting, a building, an empire, a consciousness—are a sort of undergrowth, or hedgerow, concealing animals, grotesques, monstrosities: a zone of mutability, so to speak.

Thus I would not by any means be the first to recognise the marginal world as alive, as a source of patterned inventive growth. But to accord it is own strictly representational status is another matter. Here is the famous Chi-Rho page of the Book of Kells, with its ornamentation as hedgerow, a habitat for small creatures.

—ornamentation as hedgerow—

– Chi-Rho Page, Book of Kells

Like a gothic cathedral, it is not an ornamentation untouched by geometrical regularities, but those regularities are impossible to read in their entirety from any one vantage. It is centreless, just as those monks on Iona, or Lindesfarne, occupied the margins of a world which had no centre; a world not unlike our own universe. This is a privileged situation, one bettered only, I imagine, by inhabiting the centre of a world with no margins.

![]()

...which I did, on my allotment, in a fit of autumnal glee...

This was before the foundation of the Ideal City, and subsequent to quitting my job. It was a time, in other words, when I can be said to have floated free of all social ties. I knew no one, saw no one, and spent up to twenty-two hours of every day sitting in my room.

So it was that I grew tired of looking at the bulging remnant of my intellectual dreams, the files and notes and false starts and printouts. I stuffed as much of it as I could carry in a rucksack and walked it down to the allotments, where I left it in a pile and came back for the rest. I burnt everything I had on my computer pertaining to my academic life on to a DVD, a little pre-inferno, and took that down too, with the rest of the papers.

Clarke says he saw me that evening, a sorry Viking in the firelight, in the mud of the allotments, watching a conflagration of papers. He knew, he said, that something was ending, something else beginning, down there. He had seen it before. We burn Guy Fawkes, after all, at the outset of autumn, in order that it may help the crops.

![]()

...full, predictive taxonomy...

Later, in the office, Emmet Lloyd shows us the digital manifest of the nursery. It is a real-time map of operations. Mousing over one of the colour-coded plots brings up detailed information on batch sizes, stage, condition and so on. What I took to be medieval hundreds, subject to a tacit understanding on the part of the nurserymen who knew the borders and histories and soil-types of the plots from gnarled years of experience, are in fact rigorously defined and docketed zones; the nurserymen, it transpires, carry barcode readers.

Lloyd is proud of the operation, and as a pragmatic organisation of the Ur-Nursery it is impressive. But it is, ultimately, nothing more than a catalogue, always running behind whatever is actually happening out there, in the fields and greenhouses.

A catalogue has no predictive power. It tells you nothing, or next to nothing, about total-plant-space. A taxonomy, properly understood, tells you precisely everything you ask of it. It can be argued that Linnaean taxonomy is nothing more than an elaborate nomenclatorial system—it overlays the actual relations of plants only arbitrarily. But that arbitrariness is its strength. By selecting a fixed number of variables the taxonomist can control how many taxa will be called into being. It is thus a gradable system, and one which, like the periodic table, allows for exempla which have not yet been discovered, or do not in fact exist.

It is a godlike dominion. It is not necessary to see something, not necessary for that something to be anything other than imaginable, in order to exact tribute from it.

![]()

...dare not look her in the eye...

Returning from Cobham to Kelley’s garden, and entering there by the back gate with the plants I have bought, I bring Solomon and Hunter Sidney into the garden. We deposit the plants near the back wall in a concealed space which I call the workshop—there are a couple of compost bins, the overgrown greenhouse, a broken down potting shed containing tools.

And there we stand, exposed, where Hunter Sidney is concerned, on the screaming edge of creation, in the garden of his twenty-year-lost love. He is, as he describes it later, suddenly centre-stage in his own world, bathed in the illumination of a thousand arc lamps, exposed, vulnerable, unprepared, exhilarated. But the auditorium is empty. She does not come out. She cannot have the first idea we stood there for two minutes, inside her circle of fire. The auditorium is empty and the script—there is no script—unspoken. As though, he says, he had been a ghost in his own life and had only realised it, there at that minute.

Later, recalling the moment, he wonders if this thicket of emotion and memory is in fact rooted in the originary experience at all. The Ur-emotion, insofar as it can be distinguished, was an approximate, unproportionate chemical activity, a sort of carpet bombing of the soul. The precise weight of a given experience should only be measured rationally, temperately, cognitively, he says; as though each man and woman were historian of his or her own soul. But the memory of our emotion is a corrupt dataset: we cannot recreate the experience from it. We can only generate from it an ever diminishing, qualitatively distinct, cognitive simulacrum with its own, distinct, emotional purpose.

Hunter Sidney is close to death, and far removed from the day to day commerce of the emotions, of the account book of predicaments or the currency of situations, which, insubstantial network though they be, still sufficiently ground our psychic life. But in saying this he alarms me, because he has experienced this night garden, not as a field for taxonomical study, nor certainly as what Solomon calls a library of forms; but as an existential rush of fear and hope.

I note as footnote to this footnote that some years after the end of my relationship with the woman who, it amuses me to think, galloped like a witch through my defenceless life, I met her again. I was still in love with her, she not with me. It was a friendly meeting, but I could not look her in the face, no more than I can stare unblinking at the sun. And some suns, as Hunter Sidney can attest, are black holes in the making.

![]()

...sustained illusion of presence.

The Presence generated by an image is an illusion, but it is a persuasive one.

After I quit my job I sat for months in a room by myself watching Star Trek. Captains Picard and Janeway, Commanders Data and Sisko, these were real to me, present, while I watched2. They filled the space in which I was sitting. But when at some point each day I turned off my computer, I found myself sitting alone in a darkened room, and knew that I had been sitting, alone, in a darkened room for hours past. I had at some level strongly registered presence of real people, even though the images I took for real were tiny actors, filmed years ago, centimetres tall. It was a false positive.

In the same way, photographs of the dead and the lost seem to return them to us for as long as we look, and conjure a false positive of presence. We are not furnished with psychological parts fit to process such inputs, to distinguish between actual and simulated presence. Where the past used to compost its memories, create from them something useful, we now find the dead turning up with remorseless regularity, perfectly preserved, like peat burials.

Hunter Sidney, who spends long hours together not speaking because of the strain of using his artificial voicebox and more latterly because of the pain of the cancer in his throat, says that he now experiences the same false positive when he is actually in the presence of other people. Presence and absence, he says, are useful categories, ones which it would be pointless to empty of meaning, like a bored philosophe; we know, usually, when someone is with us or when they are not. We are not fools. But for a silent man, the presence of others starts to look and feel a lot like their recorded absence; like looking at photographs or television. Like watching Star Trek.

![]()

... distinct locales, Flemish and Dutch.

The patterns of survival and persistence (both of individual works and of tradition) are not merely the outcome of a simple geographical dispersal of iconoclasm.

At the time of the great Beeldenstorm or Iconoclasm of 1566 and subsequent iconoclasms in, for example, Antwerp in 1581, Protestantism was more firmly rooted in the (latterly Catholic) South, and Catholicism in the (now firmly Protestant) North. And the Beeldenstorm started in the South and touched Ghent and Antwerp earlier and more fully than the northern towns.

The economic centre of gravity shifted significantly from the Southern Netherlands (Ghent, Bruges, Antwerp) to the Northern Netherlands (Amsterdam) over the course of two centuries. The Northern Netherlands could successfully defend its independence against Spain by breaking the dykes and flooding the polders, the Southern Netherlands could not.

Flemish art was already diffused across (mostly Hapsburg) Europe by the second half of the sixteenth century, and can still be viewed to better advantage in Madrid and Vienna than in Belgium. The same cannot be said for the less prestigious Dutch art of the same period. Thus the output of Pieter Aertsen (1508/9-1575) was more vulnerable than that of Pieter Bruegel, to take one example, and his greatest works—altarpieces, public art—were mostly destroyed.

Unaccountably, but mercifully, his Egg Dance was overlooked.

—unaccountably, but mercifully—

– Egg Dance

Pieter Aertsen

![]()

...according to legend...

The legend holds that a painter, sent by King Abgar of Edessa, had been trying and failing to capture the holy visage, but now brought this divinely stained cloth back to Edessa where it cured the king of leprosy.

—unaccountably, but mercifully—

– Abgar of Edessa receiving the Mandylion from Thaddeus after 944

In accounting for the sudden appearance of the object in the sixth century, Gibbon notes that "The ignorance of the primitive church [of the existence of the Mandylion] is explained by the long imprisonment of the image in a niche of the wall, from whence, after an oblivion of five hundred years, it was released by some prudent bishop, and seasonably presented to the devotion of the times."3

The object is blurrily distinct from the sudarium of Veronica, whether by heredity or convergence, I cannot say. But both legends are contiguous with the practice of pilgrims, whereby relics were wiped with a cloth (brandea) in the hope or expectation of magical transference. Presence is registered in the image through a matter-of-fact transmission by touch, rather than any more airy metaphysics.

![]()

...whatever its limitations...

Hannah Arendt points out, accurately if dourly, that all art works are dead:

“We mentioned before that this reification and materialization, without which no thought can become a tangible thing, is always paid for, and that the price is life itself: it is always the “dead letter” in which the “living spirit” must survive, a deadness from which it can be rescued only when the dead letter comes again into contact with a life willing to resurrect it, although this resurrection of the dead shares with all living things that it, too, will die again.”

The Human Condition p.169

I am moved to speculate that if a photograph is acheiropoietic, then a digital photograph is doubly so. Unlike Hunter Sidney, I have numerous images of my former beloved buried on defunct drives; like so much flaking papyrus, those pure and hieratic registrations are no doubt steadily losing information, corrupting, degrading.

They retain, however, in consequence an augmented totemic power. Those radioactive fragments of holy text are enough, you sense, to conjure from any minor psychological affliction a malevolent and largely fictional goddess.

![]()

Bless the Pequod!

Clarke's suggestion. He once shouted this at the old Polish pope on the feast of the Immaculate Conception (8th December), when the pontiff traditionally performs some mumbo jumbo before a column near Piazza Spagna on which is a statue of the Madonna. No doubt the Madonna works miracles, and demands veneration (proskynesis) in recompense.

The Pope, says Clarke, being driven swiftly back to the Vatican amidst the acclamation (douleia) of the crowd, heard the shout for a blessing and obliged with an approximate waggle of the finger.

The Pequod was a small inflatable rubber dinghy which Clarke had purloined somewhere or other, and used for little trips on lakes around Rome. It pleased him to think, he said, as he paddled up and down, that his vessel was now on an unsinkable mission from a vanished god to whom he had never offered so much as a tittle of worship (latreia).

![]()

...contemplating, although I do not know it, its destruction...

I should state for the record that Hunter Sidney did not destroy the photograph nor the Etruscan lamp which I learnt later he was carrying in his pocket. In fact when we left that afternoon he set them both on the shelves of the library, like a Mr Benn suphurously returned from the plains of Tartarus. He was never to return or see them again.

In the course of the conversation surrounding his purloined photograph, Veronica de Viggiani had persuaded him to allow us—me, in fact—to set up a meeting with its subject, Mrs Isobel Easter. But that was not why he spared the photograph. He spared it because it had been taken shortly before he came to know the woman.

It shows some dignitaries at a football match. Both Tony and Kelley—and Kelley’s wife—are present, so I should say that it was a match between Norbiton FC and Kingstonian, taken towards the end of the 1980s before Tony dell’Aquila’s takeover of NFC and the amalgamation of the two teams.

I would guess, further, that it was taken around the time of the construction of the Palladian North End. The group of dignitaries seem to be standing at the rear of some old concrete stand, and there is evidence of construction work going on in the background—bags of cement, piles of bricks and a yellow cement mixer.

If you were moved to paint a fresco cycle of the building of the Palladian North End (for an account of which see Architectural, here), or of the Life of Mrs Isobel Easter, this would perhaps be one of the narrative moments you would choose to depict.

Hunter Sidney met Kelley's wife after the Palladian North End had been demolished.

![]()

...the encirclement of the Devilish Turk.

Belgrade had fallen in 1521, the year after the accession of Suleiman the Magnificent, and in 1522 the Knights Hospitaller were driven out of Rhodes. The Hungarian forces were defeated at the battle of Mohács in August 1526, and by 1529 The Turk would be at the gates of (Hapsburg) Vienna.

—The Turk—

– Suleiman the Magnificent, c.1530

– Titian (attr.)

The geography in Suleiman’s head will have been very different. He had his own troubling borders—for instance that with the Safavid Persians with whom he fought a series of long and inconclusive wars. Moreover there was a long history of Ottoman alliance with Christian Princes, such as theat with the French between 1542 and 1546.

But the trope of the devilish encroaching Turk has a substantial pedigree.

Milton, to take an anachronistic example, refers to Satan as the Great Sultan, and describes his return from Eden by freely mapping the geography of the East on to that of Hell:

As when the Tartar from his Russian foe

By Astracan over the snowy plains

Retires, or Bactrian sophy from the horns

Of Turkish crescent, leaves all waste beyond

The realms of Aladule, in his retreat

To Tauris or Casbeen.

Bk. X, 431-436

And a little later we read of the devils (the ‘great consulting peers’) as ‘raised from their dark divan’ (456-457)

![]()

...has been variously read...

Bruegel was at the centre of the humanist circle in Antwerp, a friend of the printer Christophe Plantin (1520–1589) and the geographer Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598); and while the picture is clearly derived from demotic or folk forms channelled through Bosch, its literary sources are Classical (Margaret Sullivan notes4 in particular Seneca’s On Anger, Horace’s third satire, and the description of Avaritia from the Psychomachia of Prudentius).

The painting has much in common with an earlier engraving by the same artist from his sequence of the seven deadly sins, Ira.

—much in common—

– Ira, c.1530

– Pieter Breugel (engraved Pieter van der Heyden)

Each of Bruegel’s depictions of the seven deadly sins follows the same compositional pattern of an allegorical figure surrounded by exemplification in detail. Since, Sullivan argues, there was no clear allegorical type for Madness, Bruegel developed his own along.

Madness is akin to anger. Seneca (selections from whose works were published in Antwerp by Plantin in 1555) regarded extreme anger as a revolt against sanity, and according to Erasmus anger and madness coincide most nearly in the waging of war between Christian princes. Anger can be induced by gluttony (especially alcohol), and avarice. Each detail in the picture can now be related to the operations of gluttony, avarice or anger insofar as they are the offshoot of (artificially induced) Madness or (natural) Folly.

It may also be the case that the two central figures are allegories of the Protestant or heretic revolt on the one hand (Madness) and the Catholic hierarchy on the other (Folly), both at large in a pre-revolt Antwerp, where the iconoclastic Storm of 1566 was only four years away, (by which time Bruegel would be gone, working in Brussels), and the start of the Eighty Years War only two years beyond that.

![]()

...perhaps date from the Neolithic.

It is hard to date petroglyphs, for obvious reasons. This for example, from Cornwall, has been variously assigned to the Neolithic and the eighteenth century, but is most probably from the latter given its state of preservation and its proximity to a set of tin miners' huts of around that date.

—hard to date—

– Rocky Valley Petroglyph, Tintagel, Cornwall

However, it seems clear that other labyrinths really are pretty old. This, for instance, from Galicia, which dates to the Bronze Age:

—pretty old—

– Labirinto do Outeiro do Cribo, A Armenteira, Meis, Pontevedra, Galicia

– Photo: Froaringus (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The earliest surviving non-petroglyphic representation of a labyrinth, from what I can make out, is a clay tablet from Pylos, dated to around 1300 BC, roughly contemporaneous with the Galician glyph.

Pylos, it will be recalled, is where Carl Blegan found the confirmatory fragments of Linear B which helped Michael Ventris to its final decipherment (see Archaeological here for an account of this). The Pylos fragment is indeed inscribed on the recto in linear B.

![]()

...there is a single unicursal path.

Actually, this is not true. While for most their history mazes were merely broken unicursal labyrinths which could be reconstituted into their original unicursal path—which is to say, solved—by the simple pragmatism of keeping one hand at all times on a wall; from the early nineteenth century efforts were made to ramp up the complexity, either by isolating the centre by the simple expedient of floating walls, or by creating multiple routes to the centre. Nevertheless, it remains the case that if a labyrinth is soluble and if there is a user of that labyrinth—a Theseus, a Minotaur, a Daedalus—or in other words, where the labyrinth has not just a topology but a history, then there is a steady convergence of paths trodden and permissible routes: a convergence on a single unicursal path.

I am prepared to admit, however, that at this point we should probably stop using the terms multicursal and unicursal. In the interest of clarity.

![]()

...and in the petty detail.

Hunter Sidney has decided against curative treatment for his cancer. He has elected only to moderate the pain, and to stay at home. It is time, he says, to make the necessary preparations, amongst which he numbers extricating himself from The Love Filter, his deepnet multicursal fiction [for an outline of which, see Bureaucratic, here].

Extricating himself means, in part, handing over his passwords and connections and stubs to a fellow editor. This he has done. But in part, he says, it involves relinquishing the persistent desire he has had throughout the Love Filter project to develop a technology for closing doors behind readers as they made their progress through the work. It was his wish, he says, to constrain the reader into one reading only, so that each reader's experience would be a unicursal path across a multicursal plane of possibilities.

No such technology was put in place; he relied instead on the general inertia of readers. They surely would not go back on their path once they had properly got in, more than a fork or two anyway. In general they would be propelled down a single path of their own making.

He is now relaxed about the exploratory instinct taking hold. The thing is sufficiently big that no single reader could exhaust all possible narratives. The best they could hope for would be to cut out a broad path rather than a narrow one.

For the twenty years he spent immersed in The Love Filter he felt, he says, like a hunched miner, tinkering on artefacts and stories, speculating about the goings on up in the sunlight, with only the muffled intermittent sound of picnics and jollity to guide him. Now that he has emerged from that cave he feels nothing but relief. There was no end to the caves down there, no one could know them all. But he knows many of them, more or less how they are laid out.

As I say, he has surrendered his editing duties to a colleague, and given her some stubs of stories he was working on. I learn only later that the colleague in question is Veronica de Viggiani. But I should have guessed it.

![]()

...and used it for floor mosaic...

As did my father.

My father as a young man took considerable pride in his instinct for interior decor. At some point in the 1960s before I was born, perhaps before he was married, he bought a carpet of Greek Key design. It was a dark blue key against a dark green background, if I recall. We moved house often in the first decade of my life, and the carpet came with us each time, being cut again and again to fit its destined bit of floor; so that by the time we settled on a house in the late seventies, it was dispersed in offcuts here and there, some under a bed, some filling a blank space at the end of the hall, bundles of misshapen oddments rolled up in the attic against any future move.

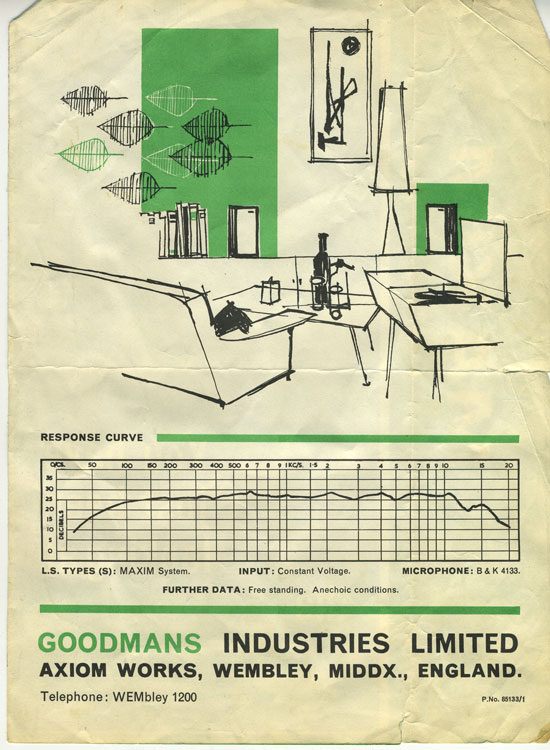

Piecing the carpet back together might have had some sort of (insane) therapeutic value for my father, had he ever grown tired of his whisky and cigarettes; he could have traced his life back along the labyrinthine dismemberment of the meander motif to a point where he could confirm that once, before the threads of organisation got lost, he had cared about the material organisation of his life, standing there on his Greek Key carpet, a modestly suave bachelor with his Quad hi-fi and his neat little Goodmans speakers, and his Conran furniture, and his whisky and cigarette.

—modestly suave—

Goodmans speakers brochure, c.1965

![]()

...one afternoon after lunch...

This was my ritual treading of the labyrinth, I suppose, on Hunter Sidney's behalf, the labyrinth in question being Mrs Isobel Easter's set of rooms, her elaborate but unobtrusive etiquette of deflection.

I am no Theseus, and Mrs Isobel Easter is no Minotaur. But in some traditions, notably the Cretan, the Labyrinth is host to a female deity—the Lady of the Labyrinth—before it is host to a bull-headed man.

So, while there remains to a rational being something monstrous about even the most benign deity, perhaps my analogy is apt.

The heart of her labyrinthine world, its generative nucleus I suppose I must say, is the room I call her studiolo, which I gain now for the first time. While this room is not physically inaccessible—you could simply walk in the front door and up the stairs and in—it lies in a charmed circle. Merely to bluster through the front door would be to cross any number of invisible social, personal barriers. It would be unthinkable.

My arrival here has been instead by a series of circuitous stages. I typically enter the garden by the back gate; if I see Mrs Isobel Easter at all, she may or may not invite me in to the kitchen to drink my tea; a couple of times I have been invited up to her outer room—the room I call her grotta; and now for the first time I am invited to step through into the studiolo as though it is the most natural thing in the world.

It is a corner room, clean and sparse, with two large windows, a slender desk and a spindly chair, a narrow sofa upholstered in pale yellow and a single high-backed armchair, also in pale yellow.

I had been expecting to broach with her the possibility of a meeting with Hunter Sidney; it would mean mentioning his name for the first time in her presence, acknowledging openly their connection; but to my surprise, having been invited up and into this inner chamber for the first time and sat on the sofa with a cup of tea, she diplomatically indicates to me that she would be ready to receive an old friend of hers the following afternoon in the battered summer house in the garden, should I wish to arrange it, at around two o’clock.

She does not mention his name. But on some pretext or other she does produce an old photograph album and leaf through it, showing me, or letting me see, a cluster of pictures of her and various friends taken as I know towards the end of the 1980s; pictures of her and Ted Kelley, old Tony dell’Aquila, the Palladian North End; and one of Hunter Sidney in Rome.

It takes a sharp eye—I have a sharp eye—to notice that the solitary picture of Hunter Sidney, which she lets me glimpse for not more than two seconds, is of him standing on the Pincio, overlooking Piazza del Popolo; and that over the lintel of the door which connected Mrs Isobel Easter’s studiolo with her grotta, was a veduta of that same square.

![]()

...reconstituted Norbiton FC...

Clarke has put together a squad to take on a Kingstonian XI, as follows:

Civ Clarke

Solomon

Veronica de Viggiani

Ted Kelley

Emmet Lloyd

Konrad Moscicki, formerly of NFC and Kingstonian

Steve Moscicki (Konrad's son)

One of Cannoner's nurses

One of Emmet Lloyd's nurseryhands

One of Ted Kelley's masons

One of the waiters from the New Devi Tandoori

Me

I like to think of our team as an Ideal City representative XI, but Clarke is firm that it is the wheezing ghost of Norbiton FC.

Prior to the game itself, we manage a few inexpert practice sessions.

Nestor props himself on a fabric camping chair, hands on his walking stick in front of him and chin on his hands. He wears a pair of black sunglasses, and has put on a tie for the occasion, and a jacket. He had argued that all he needed in order to coach us was an amanuensis who could supply him with an adequate description of the game. There is football, he said, and there is a description of the game of football; at the nexus of these two, lies clarity of understanding.

He has settled for this purpose, a little surprisingly in the light of his stated requirements, on his Bolivian housekeeper, a woman whom I have never heard speak English. She sits next to him and knits, keeping an eye on the football; occasionally she leans over and mutters into his ear in Spanish, and we see him nodding and musing. Every so often he explodes with incomprehensible instructions which Clarke translates for us, out of the depths of his ignorance.

And in this way we make our small and often retrograde progress. Notwithstanding the intellectual clarity of Nestor’s mental chalkboards and the emotional clarity of his terrifying spittle-filled touchline pantomimes, we invariably congregate on the ball, or on empty space, as hazard dictates.

![]()

...subsequently described by Plutarch...

Plutarch (AD 46 – 120) lived many years after Virgil died (BC 70– 19), so I mean that he referenced the dance, not the description of the dance.

However, clearly I have confused and anticipated matters in my own head—a properly labyrinthine befuddlement of scholarship in this instance. The Crane dance anticipates the Virgilian carousel by several centuries and Virgil makes no specific reference to it, nor does he describe the Trojan display as a dance. All of these elements are in fact drawn together in a description of Catherine de’ Medici’s Ballet des Polonaises by Jean Dorat which I know through an article by Thomas M. Greene in the Renaissance Quarterly called ‘Labyrinth Dances in the French and English Renaissance’ (Vol. 54, No. 4, Part 2 (Winter, 2001), pp. 1403-1466). Everything is backformed from that source, so to speak.

Elsewhere in Ludic I quote a different description of the same dance, by Pierre de Bourdeille, Seigneur de Brantôme; Dorat's is in Latin, Brantôme's in French.

I say this in the hope of anticipating and heading off further confusion; but it is by now clear to me that adding detail and refinement in this way only multiplies everyone's bewilderment. It is a useless instinct in me, the mental hopping of a galvanic frog.

![]()

...which he called the Periglacial City.

Periglaciation is associated with those regions of the globe that fringe the permanently frozen regions of the arctic—thus Northern Russia, Canada, Scandinavia. There are also relics of periglacial landforms fringing the antique ice-sheets.

The periglacial is characterised by the interaction of the permafrost, a layer some feet beneath the surface which never thaws, and the surface layer which thaws seasonally. This subsoil boundary and the differential movement it implies, and the seasonal saturation of the upper layer, account for a number of landforms peculiar to periglacial areas: frost-heaving, hummocks, hydrolaccoliths, sorted stone polygons, and so on.

—hydrolaccoliths—

melting pingos or hydrolaccoliths, near Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, Canada

– Photo: Emma Pike [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

—sorted stone polygons—

Stone Polygons, Svalbard

– Photo: Hannes Grobe 21:14, 26 October 2007 (UTC) (Own work) [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

There are probably Northern myths—Siberian, Norse, Inuit—of periglacial tundra gods whose feet are rooted in ice like thwarted and tormented Prometheans; or of felt-wrapped shamans stilling their pulses and descending into the permafrost to secure crystalline visions. There are certainly modern mythologies, of chain-wheeled mining corporations, hurtling meteorites, preserved mammoths.

And there are fragmentary personal mythologies. When I was seventeen, studying geography A-level, a field trip was mooted to Lapland. We would go up there, pace out the hydrolaccoliths, squidge the hummocks, lasso reindeer, catch walrus through holes in the ice, drink phials of 80% proof potato spirit against the cold—who knew? Anything seemed possible.

The trip never happened. We went to Cornwall instead, stayed in Bude, and drank beer. I have never been to Lapland, and am far from committed to its existence.

—far from committed to its existence—

A Sami man and child in Finnmark, Norway, circa 1900

– Photo: Nasjonalbiblioteket from Norway [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons