Melancholical

—melancholical system—

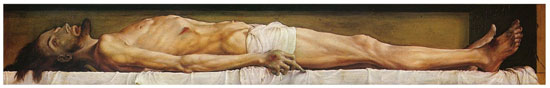

– Dead Christ

Hans Holbein

What is a city, if not a natural anti-melancholical?

The Renaissance magus understood this: what most looks like melancholy, what grows near melancholy, cures melancholy1. Walnuts are good for the brain, a dock leaf relieves nettle stings. A city then, being nothing so much as the raised up detritus of activity, of busyness, is the object best fitted to assuage our melancholic temper.

But where is this melancholy generated—this melancholy that the city cures and counterbalances—if not within the city itself? Each city is an engine of its own melancholy, its own poverty, sickness and misery, all engendered by the growth and health and freedoms of that same city.

The city in short is a melancholical system.

It logically follows that Norbiton: Ideal City in its heyday, so far from simply being an anchor dropped in melancholy space, was at best half an idea: a sort of melancholic free radical.

Small wonder it failed. Just as action without its melancholy sump is a form of insanity, so contemplation without the skeleton of action is a variety of depression.

And there we have it. Norbiton: Depressed City.

![]()

The burgeoning and healthy city is, to repeat, a melancholical system. In Florence in the Renaissance, as in other medieval cities, great monasteries were planted here and there like public utilities, power stations or sewage works of the soul with their gardens and their hospitals and their charitable acts, establishing a humoral hydrostatical relation with the city's intoxicating, hysterical stadt-luft-macht-frei of commerce and trade and unbonded labour.

These communities institutionalised the requirements of solitude, tranquillity, and charitable action. Richard Sennett, talking of medieval Paris, notes that monastic spaces were open to the city, with low enclosing walls and open gardens2. From the thirteenth century, the Servite community on the Right Bank began to use lay members as almoners, a practice soon followed by other monastic houses. Monasteries were becoming civic institutions, and monks in their cells were wired in series for melancholy, a great wet cell battery.

Clarke wonders, in a moment of prodigious clarity, whether we were building in Norbiton not a city, but a monastery.

—prodigious clarity—

We were, he implies, a coenobitical community. We were not tainted with all that priestly hoodoo, admittedly, nor were we bothered with asceticism or wakefulness or (in his case) taciturnity; but still, there was the gardening (scraping with hoes in our monkish vegetable patches), the concern with emblems and geometry, the routine offices of the day, the necessarily modest habits, the absence of sexual congress, the institutional rumination.

We were anchorites and visionaries perhaps, hermits rather than almoners; but there was no city—unless you can somehow conceive a city of monks and refrain from calling it a monastery.

Clarke lies on my sofa and picks his nose and I look at him, and I do indeed see a fat Benedictine, and feel a small but impotent surge of Franciscan zeal.

![]()

Whatever else you may think of him, Clarke is right to identify a humoral imbalance in Norbiton. Put all your melancholics in one place and you instigate a critical build-up of failure and melancholy. All it needs is a filament or spark of illumination. Of self-awareness.

In his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Bede the Venerable relates how the pagan King Edwin of Northumbria, visited by a Bishop Paulinus intent on converting him to Christianity, was sitting in council considering the new religion; and one of his elders illustrated the problem for him as follows:

Swylc swa þu æt swæsendum sitte mid þinum ealdormannum and þegnum on wintertide, and sie fyr onælæd and þin heal gewyrmed, and hit rine and sniwe and styrme ute; cume an spearwa and hrædlice þæt hus þurhfleo, cume þurh oþre duru in, þurh oþre ut gewite.

Hwæt, he on þa tid þe he inne bið ne bið hrinen mid þy storme þæs wintres; ac þæt bið an eagen bryhtm and þæt læsste fæc, ac he sona of wintra on þone winter eft cymeð. Swa þonne þis monna lif to medmiclum fæce ætyweð; hwæt þær foregange, oððe hwæt þær æfterfylige, we ne cunnun. For ðon gif þeos niwe lar owiht cuðlicre ond gerisenlicre brenge, þæs weorþe is þæt we þære fylgen.

It is as if you and your great lords are sitting feasting in the great hall in wintertime; the fire is laid and the hall warmed, and it rains and snows and storms outside; a sparrow comes and flies rapidly through the hall; he comes in through one door and goes out at the other.

While he is inside he is not touched by the winter's storm; but it is an eyeblink, the briefest interlude; from winter to winter he returns. Such too this human life appears, a mere interlude; what goes before and what comes after, we cannot know.

Therefore if this new teaching can bring us any greater clarity, then we should follow it.

Note that it is neither the sparrow, nor the revellers, nor the hall, nor the night that carries the melancholy; the melancholy is generated by the system of relations. King Edwin is invited to consider himself as that which is puzzling, and that which is puzzled: the king at his feast, and the sparrow flying through the hall. The king at his feast knows what is outside in the stormy night—the houseless poor—and he knows that the day will come and the storm recede. The sparrow too, in his way, knows that the feast is an illusion, if of a different quality. He flies through the World like a filament of mystified worry.

And so on. This is our city—a perpetually self-aware melancholical system. Norbiton: Ideal City is London's sparrow.

—cume an spearwa—

– Landscape with Bird Trap

Pieter Brueghel the Younger

![]()

Perhaps there are alternative, pioneering forms of melancholy urban organisation. Take for instance the city Clarke designed at art school, which he called the Periglacial City.

Clarke envisaged that periglacial cities would be located over the last viable sources of fossil fuels, in the arctic and tundra, in a distant age of global cooling; people would gravitate to the mining stations and refineries, as to the last vestiges of warmth and organisation.

—last vestiges—

Conditioned by the impossibility of burying anything in the permafrost, the City would be susceptible to drift. Its dwellings, which Clarke called swaddlehouses, had no foundations, but were balanced like barques on the springy tundraic ocean.

—swaddlehouses—

His sketched designs (of which none remain) mimicked the landforms associated with periglaciation: they were hummocky, tufty, geometrical like sorted stones. The whole city, in fact, was a self-sorting geometrical object. But this was not ideal geometry, it was emergent, a heaving unequal geometry generated by the crude insensate sifting of matter, the gelifluctions and solifluctions of city life.

—self-sorting geometrical object—

For nine months of the year the inhabitants did not put their noses out of their swaddlehouses, and could only sense the presence of their fellow citizens oneirically, in the city which they dreamt together. They slowly burnt down their stocks of peat and lignite, inured to the dense moist smoke which escaped from the flues and cured them and their children and their felt and fur furnishings so that everything was tight and leathery, resistant.

The smoke which did not escape the flues was guided along external pipes; so too the sewage waste which was pumped in thick overground pipes, in and around the houses; human circulation was reduced to this piped warmth, a city warmed by its own effluent.

—piped warmth—

And it was a city whose cultural goods would be shaped by the cycle of freeze-thaw. Whatever was thrown out in summer and squelched into the mud would re-emerge seasons later, sorted into polygons of detritus, a universal ornamentation. Locked as they were into a perma-curfew of the spirit, the inhabitants would light on these meaningless patterns to shape the arts and commerce of their periglacial age.

![]()

The only thing that would bring them out in the winter, Clarke ruled, would be a funeral. A funeral was not a celebration or memorial, but a chance to stretch the legs. Since inhumation would be impossible, bodies were to be burnt on a public pyre, the citizens gathering for a little warmth and fresh air and the chance to see the snows pushed back in one spot, and for a time only.

—snows pushed back—

– The Funeral of Shelley

Louis Edouard Fournier

![]()

What does the death of an individual mean, in a city of great stone buildings? A city is not its people, after all. People merely wash through cities.

—wash through—

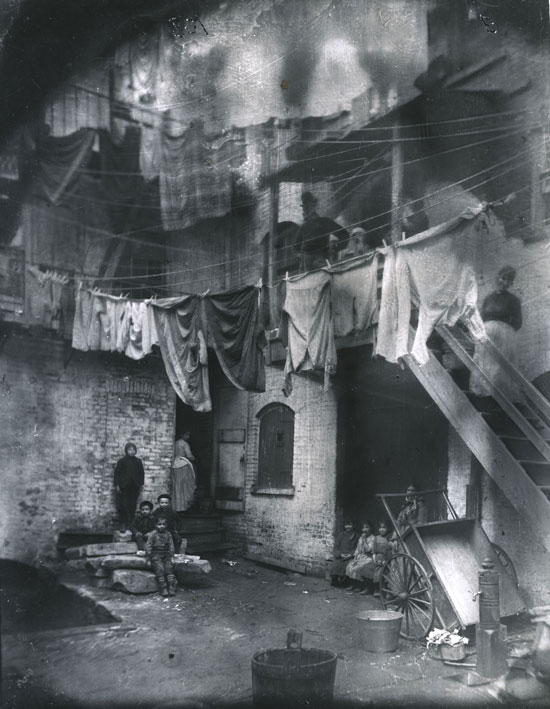

– Tenement Yard, How the Other Half Lives

Jacob Riis

And yet the death of an individual, I have observed, removes a gravitational mass from whatever system or systems he or she inhabited. It is an absolute removal—that is to say, there is no Newtonian compensation, no balance of equations. The dead individual is not dispersed as energy or matter in measure equal to their living and coherent presence. They are simply gone and the system has to readjust in any way it can. This may or may not be difficult, may or may not be a relief; it may or may not, in fact, be perceptible, since we are all locked in a complex of overlapping systems. The readjustment may be fractional. But it must happen. However it is, in the penumbra of this sudden absence, this new nothing, there is, frequently, a stasis, the circuit of objects grinding for a time to a confused halt.

The stasis in question is properly understood as melancholia, a systemic loss of purposive or directed energy.

![]()

Is melancholia a form of insight?

In his 1943 Monograph on Dürer, Erwin Panofsky provided a reading of the 1515 engraving Melencolia I, along such lines.

—form of insight—

– Melencolia I

Albrecht Dürer

This, claimed Panofsky, is a representation of creative stagnation. The figure of Melancholy is a stymied intellectual artist; the putto scribbling furiously, by contrast, is emblematic of the practical craft uninformed by theoretical direction. It is the intellect which is stymied, not the hand.

Stymied by illumination. We are witnessing not a gestation, but an aftermath. The vision has come and gone, is spent. This is what knowledge and understanding look like.

![]()

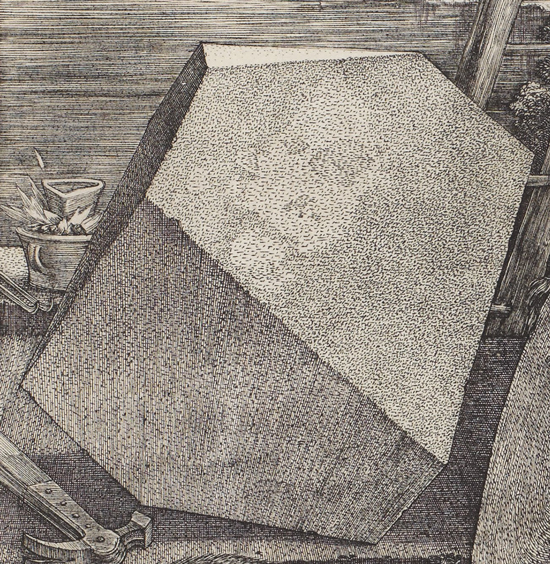

The impotent litter of the foreground and the clarity of the background are separated by a great block of stone, a truncated rhombohedron.

—truncated—

– Melencolia I, detail

Albrecht Dürer

A rhombohedron is essentially a slanted cube, where the faces are rhombi rather than squares. The truncation is at the corners. Panofsky reads this, and the turned sphere in the left foreground, as symbols of the architectural understanding which underlies the craft of building. That may be so. But the cube, I would argue, is a special case of the rhombohedron, not an ideal form from which the rhombohedron deviates. The rhombohedron is not, in other words, a Failed Object. Rather it exemplifies the condition of all objects.

And in the same way, architecture is a working from structures characterised by asymmetry, and by more complex unreadable symmetries, towards special cases of legible symmetry known as buildings. A building is a special case of nature; a building of architectural weight in a city is a special case of that city.

Buildings, in other words, and cities, have histories. They do not deviate from symmetry and clarity—they are their own crude and ungainly selves.

The figure of Melancholy, according to this reading, is not only an architect, and a failed architect: she is architect of a Failed City.

The world, we can philosophically conclude, is everything that is a mess.

![]()

I am veering, ineluctably, from the individual death that is on my mind.

Or as Clarke, lying on my sofa, continually reminds me, the mythico-twin-death. Clarke is much struck by the fact that Hunter Sidney and Cannoner died within a few hours of one another, over the course of a single chilly night at the beginning of autumn. Cannoner died in the Kingston Hospital, and Hunter Sidney died at home, in what had been his bedroom but was now his death room.

Both a death room and a hospital ward are archetypal melancholic spaces, spaces characterised respectively by the two extremes of stasis: the one, prostration, incommodiousness, and paralysis; knitting relatives, ticking clocks, horrid anticipations. The other, by relentless routine activity, your last moments passing in a blur of bureaucracy and activity as you try not to get in the way. While I spent time at Hunter Sidney’s bedside on the afternoon and evening and through the night of his death, alternating the vigil with Monica de Viggiani, Clarke was spinning around Kingston hospital in a manic attempt to piece together something from the wreck of Cannoner. Cannoner had died in the early evening and Clarke had formulated a crazy plan to purloin his body for the night and stage Anatomical Man [Cannoner's Failed exhibition, for more on which, see here] with the artist’s corpse integral to the exhibit.

Cynicism is often the best defence of a sensitive soul; but Clarke’s cynicism appals me.

He related to me afterwards how he had found himself at midnight in an office desperately composing and printing off flyer-announcements and press releases for the one-day-only show, thinking how perfect it would be if, like the saintly monk Zossima in the Brothers Karamazov the body started to putrefy, an inverse Lazarus, so that a visit to the exhibition would entail a lot of appalled nose-holding.

—nose-holding—

– Raising of Lazarus

Giovanni di Paolo

This thought had not arrested so much as egged on his preparations. But two hours later he had fallen asleep on an orange plastic chair in the exhibition room. When he woke up early in the morning, a Lazarus unto himself, he went to look in on Cannoner’s remains, but found the morgue shift changed, his placemen gone home, the opportunity defunct.

![]()

Perhaps Cannoner’s body would not have turned like that of Lazarus or Brother Zossima; perhaps in spite of his various personal corruptions the flesh would merely have cured and dried, shrunk to the bone.

Some twenty years before Dürer produced his meditation on stasis, Leonardo da Vinci painted a picture of Saint Jerome chastising himself in the wilderness. Not untypically for an inveterate melancholic, he failed to complete it, as though fascinated mid-daub with the anatomical under-drawing. Thus the penitent old anchorite is turned inside out, desiccated and extreme, caught in a moment of sublime clarity, his body seemingly on the point of imploding into his soul.

—desiccated—

– St. Jerome Penitent

Leonardo da Vinci

But that is that. That is where the artist, like Dürer's Melencolia, stops: at a point of maximal clarity. If there is an understanding on the part of Jerome that no one is listening, then there is a matching intuition on the part of Leonardo that no one is really looking.

I recall that, months ago, when I told Kelley and Clarke and Hunter Sidney about the Furthest South, Hunter Sidney had idly wondered what a Furthest North might look like. I am inclined now to think that it might look like this. A confused and unfinished old man in an extremity of pain. An ice man.

![]()

The North Pole may or may not have been reached for the first time in 1909 by Commander (later Rear Admiral) Robert Peary of the US Navy.

Shortly before Peary’s attempt, rival explorer Frederick A. Cook returned from the Arctic claiming to have reached the Pole with two Inuit men, Aphellah and Etukishook in April of 1908. His claim was initially given credence, but subsequently rejected when he was unable to provide detailed navigational records, and in the light of contradictory accounts given by his companions.

Peary’s claim seemed for most of the twentieth century better founded. He had been accompanied by five men (the African-American explorer Matthew Henson, who might have been the first to set foot on the Pole since Peary was unwell and travelling behind by sled; and four Inuit men Ootah, Egingwah, Seeglo and Ooqueh). But various discrepancies and shortcomings in his navigational records indicate that he may have come up as much as one hundred miles short of his goal. And circumstantial evidence suggests that he may have known this to be the case.

—come up short—

– Peary Sledge Party and Flags at the Pole (?). Pictured are (left to right): Ooqueh, holding the Navy League flag; Ootah, holding the D.K.E. fraternity flag; Matthew Henson, holding the polar flag; Egingwah, holding the D.A.R. peace flag; and Seeglo, holding the Red Cross flag.

A subsequent attempt in 1926 to reach the pole by air was made by Richard Evelyn Byrd Jnr. in a Fokker F-VII, a feat for which he received the Medal of Honor. It seems, however, that he may only have circled about aimlessly before returning to land. Again, there are discrepancies between his jotted (and erased) and published records.

When Amundsen reached the South Pole he built a cairn and left a flag. It was sight of these objects which dashed Scott’s spirit, and attested unequivocally to the Norwegian’s success. But neither Peary, nor Cook, nor anyone could leave any such material trace. The ice over the North Pole drifts. The only traces that could be left were strings of numbers, celestial observations, magnetic variation data; or anecdote—so many miles per day from that bit of land. In truth the Pole is a shifting wilderness without landmark, crisscrossed by bewildered explorers whose principle navigational aid was the lodestone of their own ego and ambition.

The first unequivocally attested assault on the Pole was made in 1926, mere days after Byrd’s flight, by Roald Amundsen (who had explored with both Peary and Cook in the 1890s). He sailed there in an arctonautilus, called the Norge.

—arctonautilus—

– Amundsen's Norge

![]()

To the watching world the Furthest North is a statistical blur; to the explorer, however, in its slowness, its approach to an absolute zero of the spirit, it is place of extreme clarity.

The clarity is not redemptive, it is merely a function of the slowing hum of matter and action. But it is a clarity nonetheless. Hunter Sidney’s death—of which I was notified by text while sitting in my allotment in the strengthening sun—introduced a similar clarity. It removed, to put it bluntly, a source of confusion—between his bleak love for Isobel Easter and my own uncomfortable memory of longing for a woman I lost some years ago. My lost Venetian love. Hunter Sidney dying meant my problem was no longer corporate, but personal, particular. I was staring down the barrel of my own woe.

Hunter Sidney once said that love was notable in my life and in the Anatomy of Norbiton for its absence3.

I think now that he was wrong. I find I have dotted this woman around the Anatomy like lumps of Orphic flesh; she is a tree in the forest in Arboreal; a stairway in a Venetian courtyard in Epistemological; she buys me espadrilles in Emblematic and jokes about her failed architecture in Architectural; she is I don’t know what else—there is no index to the Anatomy, and I have not named her so I cannot easily search. Even within the narrow confines of the Anatomy, my memory fails me.

However, I think I must have understood some time since that this woman is not a particular person at all but a representation of more general woe: figurehead of an event of psychic stasis on my part, an event which lasted some years and found its quittance that morning in the allotment, as I ruminated on the death of my friend. Perhaps this is why I have never given her a name.

In the end the emotional fire goes also to embers, to cold ashes, and you are left on your own again. You have been talking all this time only to yourself, in a mumbling undertone. And now that has stopped too. There is no longer any problem to solve, nothing to work towards. You are free to go your way.

![]()

In the 1560s, the last decade of his life, Pieter Bruegel painted a handful of what can loosely be considered genre pieces, where a Flemish village in the snows of winter plays host to a biblical scene. Among these can be counted the Census at Bethlehem, the Adoration of the Magi in the Snow, and the Massacre of the Innocents.

—and hit rine—

– Census at Bethlehem, detail

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

—and sniwe—

– Adoration of the Magi, detail

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

—and styrme ute—

– Massacre of the Innocents

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

In each case the main narrative action is subordinated to the detailed description of the scene. Holy family, kneeling Magi, massacred innocents are all texturally indistinct.

The snow and frost do not preclude activity. Children play and fight and are massacred; peasants bear fardels, build huts, slaughter pigs; dogs snarl, tussle, watch; horses wait; but the world has stopped around them.

The sixteenth century in Western Europe was a frozen century, a century of futile struggle locked in the middle of what has been called a mini-Ice Age. Nothing is happening for miles and years around them, nothing connected, that is: only this disparate and diffuse scuffling through difficulties. Everything is now, everything is small, everything is seen from high up, far away, whether Kings abasing themselves or Holy Family arriving, or child paddling on the ice alone. It is all one. We are all out here with the starving sparrows. There is no hall of feasting to fly through and marvel at, no illumination to be thrown on the heretofore or the hereinafter. Only these embattled individuals in a brief eternity of glacial woe, an oscillating, shivering survival.

![]()

“Walnut Tree Farm...is made largely of wood. It is as close to a living thing as a building can be. When big easterlies blow, its timbers creak and groan “like a ship in a storm”, as Deakin put it...He kept the doors and the windows open, in order to let air and animals circulate. Leaves gusted in through one door and out of another. Swallows flew to and from their nest in the main chimney4. It was a house which breathed. ...As I sat with Deakin, 10 days before his death, a brown cricket with long spindly antennae clicked along the edge of an old biscuit tin … Walnut Tree Farm was a settlement in three senses: a habitation, an agreement with the land, and a slow subsidence into intimacy with a chosen place.”

Robert Macfarlane, The Wild Places.

![]()

Clarke, subsiding into my sofa, notes that his Periglacial City took a fail grade. He doesn't remember why—his work was always characteristically shoddy—but it was appropriate, he says.

This was the logic of the place. It was a city that had in a sense picked up its skirts, pulled up its pipes and sewers and undergrounds, everything that rooted it to the spot; and each individual dwelling, each individual within each dwelling, was imperceptibly drifting away from the rest. The city was dispersing as it cooled. It was not an Ideal City but a theoretical settlement. An anti-city.

Similarly the Ideal City was nothing more than a dispersal of energy, a handful of incomplete and inadequate projects, a series of episodic ventures5. There was the archaeological traverse of Norbiton that did not happen; the dendronautilus that flew only in our mind’s eye over impossible forests; the arboreal city in Richmond Park; the football game that, lost 24-1, was not a football game; the model of the Palladian North End which never materialised; the library like a cairn of collective insanity; the rain garden I was building behind Kelley's house that was no more than an untidy tangle of wire and guttering in a tree. I could go on.

These projects were the vents and steaming grills and reliquary stinkpipes of forgotten endeavour. We moved, when we moved, crabwise by signs.

And while in the Periglacial City such an underground did not exist, so that in all its particulars it was a clear map of itself, it was Clarke’s insightful speculation that the process of slowing and freezing was what brought everything to the surface, disgorging the city's innards. The city was, in his odd vision, a place of clarity and openness where, if nothing much happened, it happened at least in its entirety in plain view. It was, in fact, a truly Self-Similar City, in which each individual's experience of the whole, while distinct, was nevertheless total.

Only in the final throes of melancholy self-awareness could such a city emerge.

The Ideal City, by contrast, was given to fatal subsidence. Thus my response to what I had thought was total collapse had itself collapsed, and all I was left with, sitting in a deflated swaddlehouse of my own invention, was the melancholy nub of actual and intractable difficulties.

END OF PART II