notes to the Ideal City: pt i

...lose my job...

To live with a job is to live in an occupied city. It entails an unremitting, low-key pretence. There is nowhere to escape to—the world of work is the Roman Empire of our days—but life is nevertheless an exercise in managing the impulse to escape.

Look around you. Perhaps everyone you see is playing out the same make-believe world as you, tuning in to you as you occasionally tune in to them, for scraps of intelligence. Or perhaps they have internalised their lines, in some method acting of the soul. Of one thing you can be sure, however: whatever it is they are doing, it is not work.1

We know full well what work is. Work is problematic, slow, painstaking, arrhythmic; it allows for the perfection of an object. Or it is rapid, repetitive, directed, an assault on entrenched positions. Or it is a smuggled agenda, something worried at in the scraps and corners of your day. Work can take many forms, but it involves, one way or another, a deep meshing of gears. And it has very little to do with a company, an institution, a job.

For me, the choice was simple enough. If there was nowhere to escape to, no rival town where things were different, I could still descend like a marauding nomadic Scythian on the orderly, oppressive fold of my life, with my strange ululations and my mangy dogs of war, and erase it from the face of the earth.

—Scythian—

![]()

...otium and negotium...

I take otium, in its various guises, to be a sort of internally structured leisure.

The word is variously articulated by Classical, early Christian, and scholastic thinkers (and a thinker, by definition almost, is someone who is immersed in a certain kind of otium – not someone, for example, who squeezes out a plan in a tight spot).

In the Classical world, it was contrasted with negotia publica, from which we have negotiate, and the Italians their word for shop, negozio. Negotia publica is engagement with the world, immersion in public affairs. Otium is a retreat from that engagement. But the clear implication is that whoever retreats has either at some stage been involved, and so earned their sabbatical or retirement or retreat; or has been prevented from such involvement by external circumstance or personal disability (sickness, for example, or exile).

For Augustine (354-430 CE) in his retreat at Cassiciacum near Milan, where he prepared himself for conversion to Christianity and to which he subsequently withdrew in the summers with a selection of disciples and colleagues for purposes of theological and philosophical debate, the concept of otium becomes sullied with a sort of proto-monasticism; and being, by now, a party Christian, he struggles with the moral implications of monastic retreat over the pentecostal impulse to get out in the market and convert (vita otiosa or vita negotiosa?). But otium still provides the context for philosophical and theological contemplation.

Civ Clarke accuses me of over-subtlety. He snorts at my distinctions, between Accidental Norbiton and Empirically Real Norbiton, and Norbiton: Ideal City; between failure and the Failed Life; between otium and negotium.

And while I disagree, believing an accurate taxonomy to be a form of understanding, my fresh distinctions are admittedly rooted in my confusion.

The six months I passed after quitting my job I thought of at the time as a period of otium. I see now it was, more accurately, desidia (idleness). But if I emerged (at the inception of the Ideal City) from desidia directly into negotium, did that mean that I had sidestepped otium entirely? And how then to characterise my working life? Pigrizia? Accidia? Torpor Negligentiae?

—Torpor Negligentiae—

– In my bed

John Kirby (1993)

And if I need to distinguish between laziness, idleness, and negligent torpor, should I not also distinguish between the acedia of the scholastics and the more melancholy, more graceful accidia of Petrarch?

In short, the more leisure (vacatio) I have, the more time I spend filleting and anatomising its body.

You can see why I was confused, even if you can’t see why I was confused. Perhaps Clarke has a point.

![]()

Civ Clarke, nicknamed for Lord Clark of Civilisation, is a failed artist of about my own age, or perhaps a few years older.

I think of Clarke as the Green Man, partly because, like a Green Man in his forest, all Norbiton seems to coalesce in him, he inhabits it fully, knows everyone, every stone, every stone's history, everything, glides through it all like a Renaissance magus operating with certainty in a cosmos of sympathies and signatures; and partly because there is a potent theatre of being about him: he is a monstrously large, 6'4", ripple-fatted, loose-limbed unjovial colossus who, tending to albinism, flusters passers-by as Moby Dick might fluster a school of sardines.

So partly for these reasons. But mostly I think of him as the Green Man of Norbiton because, a hospital cleaner working odd shifts in Kingston Hospital, you almost always see him in beech-green draw slacks and apple-green button-down tunic and, because of the albinism I suppose, a pair of round reflective chemical-green glasses.

He also favours bright white air-cushioned trainers for his fallen arches and a metallic petrol blue anorak, but it is too little too late: he is the Green Man.

![]()

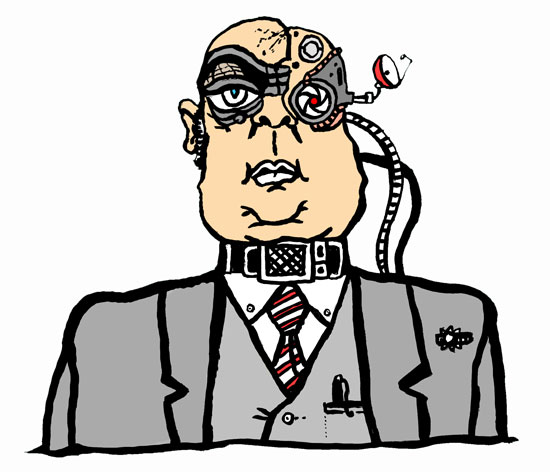

Hunter Sidney—small, sixtyish, always neatly dressed in tweeds, waistcoats, old-style civil service weekend chic—is a writer who has long since given up trying to publish anything and instead devotes his energy to collating, editing, adumbrating what he calls the anti-literature—any writing which is online, fragmentary, imperfect, unreclaimed, forgotten, outsider; in a word, unpublishable.

He used to work in some unspecified bureaucratic capacity at Shell, Shell and British Petroleum being, like the East India Company, de facto governments; but took early retirement on a disability pension. An (ex-)bureaucrat, then, gone rogue, like one of those paper-pushers at the Circus in a Smiley novel, methodically channelling spools of microfilm to the enemies of the State in clockwork handoffs, humming to himself as he puts even his betrayal in neat and docketed order.

"My aesthetic sense", he once told me, "is underpinned, by clarity. Say, precisely, what you mean, insofar, as you are able, and stop."

His delivery is halting and mechanical, because his disability allowance and pensionable status are predicated on a throat cancer which has stripped out his larynx, and he talks now by means of an electric voicebox, as though ventriloquising himself. He jokes thinly that this is but one more step on the road to the perfection of a cyborg, and that his spider-like presence in the anti-literature is a version of his consciousness, uploaded.

—hero of the anti-literature—

![]()

Clarke claims to.

He also, as it happens, talks about Le Corbusier. Clarke lives at the top of one of the squat towers on the Cambridge Estate, Madingley Tower, and from his living room window he looks out over the tiled brick residentials, the interleaved and—Clarke’s word—pointless streets.

Picture him standing there, cup of sweet and milky tea in his meaty palm, congratulating himself on the fact that down below the inhabitants have to make do, architecturally speaking, with a sort of Victorian or Edwardian suburban industrial vernacular; whereas he and his neighbours are inhabitants of the Cartesian Towers of the Radiant City.

It is standing thus that he tells me of this myth of the relocation of bombed-out Eastenders to the Cambridge Estate after the war. It is an archaeological saw that peoples do not relocate en masse: just as the Greeks were ever in the process of becoming, so too the Cambridge Estate people must have trickled to this place, dwelt here, morphed, grown, in their own way and time, radiant.

—radiant—

![]()

I realise I am getting ahead of myself—this woman, her garden, and the retelling of her husband’s mad project are all in the future—but the Ideal City is an exciting, bustling place and it is easy to lose control.

In brief then, Mrs. Isobel Easter's husband is Ted Kelley. At the end of the 1980s Kelley built a football stand at our local ground which was almost immediately demolished, partly because it was in bold contravention of every planning and safety regulation, and partly because control of the land and the football club were sold from under him, although he remains a director of the latter.

I call Mrs Isobel Easter's version of this a myth because while a certain amount of it is common knowledge—Clarke, for instance, was witness to much of it—she is the only one I know of who frames it as a move from private to public (the Great Public Work), and who is consequently able to resemble it to our clubfooted emergence. Interestingly, Kelley's own fragmentary account, which I give elsewhere, emphasises the solitariness of his pursuit, as though it were an extension in brick and stone of his private manias.

![]()

Clarke when I met him was already an Apostle of Failure. It was the end of my six-month solitude, or otium, or reconfiguration, of which I have written elsewhere, and he rose up out of the mud of the allotments resembling, not a green man exactly, more a white underground tuberous man, the risen spirit of dark horticultural order stood blinking in the sunlight.

The allotments are arranged like municipal hundreds between the kebab shops of the Kingston Road and the Hogsmill river, and abut the Kingsmeadow football ground (the John Smith’s Stand). I had taken one on in a spirit of survival after walking out of my job: growing vegetables was part of the vague subsistence plan, a way of eking out my savings and credit. The previous owner was dead, and when I finally moved myself to come and inspect my plot at the beginning of March, it was a yellowing thicket of matter, stalks and clotted leaves and rotting tool handles and collapsed trellises.

Clarke, whose shed stood in the centre of the allotments like a node of bureaucratic order in a post-apocalyptic Norbiton, came to glower over the chaos with me.

—node—

–Kingston Road Allotments

I thought he might be here in some sort of official capacity, might want to show me a book of rules, but instead he wobbled what looked like a wormy bolted brassica with the stub-end of his boot and asked if I had a plan. I did. I was thinking of digging it all over and planting potatoes, a monoculture, a cash crop.

He shook his head and told me it was a blighted patch and therefore I "didn't want to fuck about with solanaceae”.

And he wandered off without waiting for an argument, indicating that I should go with him. Clarke waved me into a wobbly old kitchen chair and started to fuss around with wallets of burned DVDs, firing up his laptop and pouring himself a cup of tea from a flask. He cross-referenced an index on his laptop with the DVDs and pulled one out and slipped it into the drawer. While it was whirring up, he thumbed through some hand-written ledgers and handed me one, open at the relevant page, pushing at it with his pudgy fingers and saying, "blighted tomatoes in twenty-oh-three, spuds in oh-seven, again in oh-eight...". I looked at the page, at the charts like portcullises, at the illegible annotations, none the wiser.

The DVD was an episode of Gardener’s World. Monty Don (his humours dangerously, secretly, out of kilter) was talking about blight. Clarke scribbled something in a wire notebook with a stubby pencil, like a fat and wheezy doctor. He tore off the page and handed it to me.

Beans, he told me, and some squashes "might do". And a row of potatoes—some sarpos, although I would not "get a decent chip off of them". And a row of King Edwards, as a control.

I folded the scrap of paper and put it in my pocket. And we sat there, Clarke drinking his tea, watching Monty Don in peaceful companionship, as though our day’s work were done and done well.

![]()

Not at all like hospitals used to be. Back in the days when they could not do any actual medicine, hospitals were great and often beautiful statements of civic virtue. We might consider the Chelsea Hospital designed by Wren, or the Greenwich hospital where Wren, Hawksmoor and Vanbrugh all pitched in. Jewels of charity on the dung heap of society.

And then there is the Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence. It is not a hospital in our sense, is more of a hospice, but a work of civic virtue, nevertheless. It was an orphanage, and it was paid for by the silk guild—portraits of leading members appear in the altarpiece Adoration of the Magi by Domenico Ghirlandaio.

—civic virtue—

– Adoration of the Magi,

Domenico Ghirlandaio

Built by Brunelleschi between 1419 and 1426, it was one of the great defining events of quattrocento architecture, in the way it integrated classical motifs and strict proportion into a free-and-easy gothic hinterland. It heralded, in art and architecture, a general straightening of lines; an exclusion, by implication ironic for a hospital, of the untidy and disorderly.

The Ospedale does not really exclude. It is, like any architecture, part of its place—in the case of the Innocenti, it stands in Piazza SS. Annunciata, speaks to the buildings standing alongside and opposite, to the streets around; it is a hub of Christian charity in a more charitable (because less benign) age, a point where orphaned impoverished children and rich silk merchants shook hands (not literally), Florentines and Christians all. There is no injustice, the building would have us believe. Only here and there in the fabric of the city a little asymmetry. And for that there is a cure.

—a cure—

– Ospedale degli Innocenti,

Filippo Brunelleschi

Kingston Hospital by contrast, like all NHS hospitals, is a fretting, fingernail-biting, feverish neurotic mess. Even if they do know how to practice medicine, how to patch you up and send you back.

![]()

I say it is not a park, but that is precisely what it is: a Renaissance deer park. It is home to emblematic stags and parakeets, ancient trees and wild men.

Hunter Sidney says that when he was a small boy growing up in a Berkshire village his next-door neighbour was an elderly woman called Mrs Kilby. One morning his mother woke him with the news that Mrs Kilby had been up at dawn and had seen a deer on her lawn. Slightly stunned by the news, he envisioned a great stag emerged from the misty forest, perhaps wounded with an arrow, breathing hard, hunting horns away off in the distance.

—Mrs Kilby goes to her window—

– Hunt in the Forest,

Paolo Uccello

Fanciful enough, but I have a similar story. When in the early 1980s my uncle lost his job he bought a concession with his redundancy money in nearby Sherwood Forest and chopped wood there, which he sold locally. Like Hunter Sidney I saw him in my mind’s eye hewing with an axe in the forest dawn, or traipsing under faggots of sticks, some medieval woodsman.

Both Hunter Sidney and I came to realise later in life that the deer was most likely a little muntjac or roe, and that my uncle in all probability had a chainsaw. There were no hunting horns, no Lincoln green. But as Hunter Sidney points out, perhaps we should have clung on to the elemental strangeness of our childhood imaginings, because both Mrs Kilby and my uncle in their different ways, in or around the forest in those early hours, must have sensed a peculiar dislocation, the oddity of a secret deer in your garden at the tail end of your solitary widowhood, of finding yourself chopping wood, alone in a forest clearing.

![]()

It was only later, after a few more drinks, that Emmet told us where he had come by the pamphlet: he had been handed it at a trade fair. Not only that, he was now in love with the woman who was distributing the pamphlets. He said she touched his hand as she handed him the pamphlet, and met his eye and smiled.

And now he did not know where to find her. The only solution he could see, he said, was to visit trade fair after trade fair, and attempt to run into her again; or to contact the company whose pamphlets she was distributing, and find from them the name of the agency which had supplied their pamphleteers, and so on. Only this information would not be forthcoming.

It is easy for Emmet to develop an infatuation like this, since non-consummation is his type of romantic love. His susceptibility and shyness demand no reciprocity, no words. Apollo to a forest of Daphnes, puffed up and inept, the thoughtless brushed fingers of a pamphlet girl were quite sufficient to unkilter his universe.

It is much the same for everyone: desire is total, consummation sporadic. Where I differ from Emmet however lies in the prevailing geometry: my own forest of desire, if you will, is gravitationally shaped by the presence out there somewhere of one vast dark tree, a woman I suppose I loved and subsequently mislaid, and in whose shadow much of my life since has been lived. For many years, in other words, I had an unconsummated longing for a woman with whom I had had a lengthy and involved affair.

This damaging and prolonged aftershock may have been merely a nostalgia, a senseless yearning; or perhaps it was a catastrophic redistribution event, the remaining elements of my life requiring time to coalesce and assert themselves. Either way, if I could climb into a dendronautilus of suitable specification I would set off across the boundless forest in search of that one tree that stands at its centre, beating back across time if need be on my futile quest, because now I would know better how to navigate away from it. The reefs, swell and currents of the forest are just that: reefs, swell and currents. If I did nothing else in the battling spray-soaked misery of those years, I charted the arboreal ocean and its treacherous archipelagos well. This time I would sail straighter.

Perhaps Emmet and I are not so different.

—not so different—

– Two Men Contemplating the Moon,

Casper David Friedrich

![]()

We lived adjacent to my father’s place of work, offices and factories producing street lights and concrete lampposts. There were a number of dumps dotted around the site, and on summer evenings and at weekends my brother and I would make a round of them, pick them over for god knows what. Our teenage world aspired to the quality of a gentleman’s library but was furnished with light-industrial detritus.

In the course of the 1980s the factories that produced the lampposts on that site were closed down. The land was sold off and they built a housing estate. There was a period of a year or so when our evening walks were through abandoned and broken down factories, crunching broken glass and the last of the spilt aggregate; and over the scrubland that surrounded and interspersed the factories and sheds and workshops, where stacks of abandoned concrete lampposts were rapidly brambling over. The desuetude was so natural and apt that they furnished the battle sets of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket with some of these crumbling posts.

Any (misguided) excavation of that forlorn housing estate, names ripped from nowhere—Furlong Way, Blacksmith’s Close, The Chase—would turn up some remarkably tedious remnants of Britain’s epilogue to the century of industry: crumbs of concrete, twisted steel reinforcing rods rusted to nothing, fragments of Formica from the canteen tables.

![]()

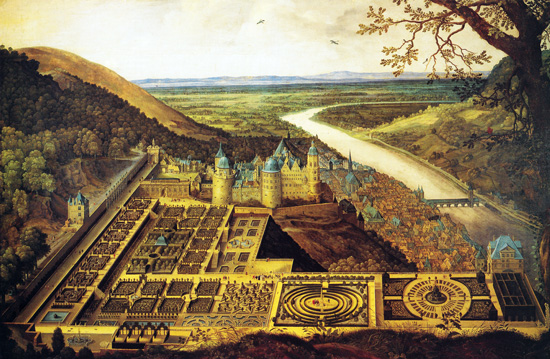

...flowerbed in Kelley's garden...

Kelley has offered me a job—a little work in his garden. He has a large garden and no time to work in it, he says. He has been thinking of getting a professional gardener, but he doesn’t want anything done really except the grass cutting and the beds weeded, perhaps some bushes cut back; so if I want the work, there it is. I say yes, why not, and we agree that twice a week I will come around at my convenience in the afternoons and do whatever it occurs to me to do.

But I know, the moment I set foot in the garden, that it will become a major project. There is no question of cutting the grass and doing a bit of weeding. It a large and involuted space which has the trick of appearing to the initiate larger than it is, and this is a function of its involution, its serpentine involvement, its store of surprise, the space compressed and maximised like the canals of the brain; as though you measured its size by the number of entrances and exits you made.

—entrances and exits—

– Hortus Palatinus, Jacques Fouquières

Two different levels link up with steps and slopes, you follow a path and emerged to your surprise at the side of the house. At the back, a long way from the house, a path less embowered than furred and hardened carries you into what should be, perhaps really is, next door’s garden, and you are confronted with a silent overgrown mossy structure, a summer house—the Pavilion of Limpid Solitude, as I immediately (in my head) call it—more limping than limpid, however, limping and wheezing, broken down by envious winters. Somewhere back up towards the main house there is a small choked fountain and pond; bleached and belichened quarter-length concrete statues of Greek gods peer impotently, humiliated, caught in their nakedness, from the foliage; you glimpse averted eyes one minute, buttocks the next, a pitcher a third; and so on as you make your round.

The garden stands away from the road and backs on to other, similarly obscure gardens and houses invisible and silent beyond, and so is as quiet as you might reasonably expect for suburbia. Someone once a long time ago went to the trouble of picking out particular plants and shrubs, tending borders, planting roses; it has all bolted or mutated, vegetable patches are home to vast and misshapen progeny of domestic species, forbs and weeds, bushes of herbs with knotted trunks, blighted and mutilated yellowing pulps. Everything is green, ferny, rotting, big, unflowering, like the imagined forests of the early carboniferous.

Not all of the garden is overlooked by the house, by any means, but I am assured by Clarke that I will be watched in my work; not by Kelley, who is rarely home when I am there; but by his wife, who never leaves the house anymore. Kelley’s wife is agoraphobic, and looking at the garden, you can understand why.

![]()

Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) was a millionaire businessman and archaeologist who was obsessed with Homeric legend. He made his fortune in Russia and then California where he opened a bank during the gold rush. He also did well in the Crimean War, cornering markets in saltpetre and sulphur. He retired in his thirties and joined Frank Calvert in his excavations at Hissarlik, gaining his doctorate on the suggestion that Hissarlik was Troy. It was on the site of Hissarlik, or Troy, in 1872 that in the process of obliterating the stratigraphic record of the city he found a cache of bronze items, which he named 'Priam’s Treasure'. He subsequently smuggled 'Priam's Treasure' out of the country. In 1876 he discovered grave goods of such richness at Mycenae in Greece that he was naturally moved to insist that they were Agamemnon’s.

He named his children by his second wife Andromache and Agamemnon, and validated their baptismal ceremonies by reading one hundred hexameters of The Iliad over their heads.

Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941) was acquainted with Schliemann, and his own Minoan civilisation was perhaps in part born of the pressing need to differentiate his work from the German's. He did not find hoards of treasure belonging to Minos or Daedelus or the Minatour, but he took the trouble to rebuild and redecorate the palace with the help of a father and son team of French painters, the Gillérons. To striking, ahem, decorative effect.

—ahem—

– Knossos, North Portico

photo: Bernard Gagnon (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

Both Evans and Schliemann believed that at some level you could see all around the objects of knowledge—so the Homeric legends and the bronze age sites at Mycenae and Pylos derived from the same small world, a world that could be encompassed by a few (immense) stories. Evans perhaps thought that in the Linear B fragments he had the key to such a story. Ventris exploded that thought into a million fragments. What Evans in fact had was the merest corner of something immense and dull, something which would take an industry of scholars only to begin to understand. Had he known how far he had to go, perhaps he would never have bothered. Similarly with all of us. It is never-ending.

If archaeology teaches us one thing, it is that we are always nearer dissolution than completion.

![]()

When he was a schoolboy, Ventris met Sir Arthur Evans by chance on a visit to the Royal Society. Ventris was 14 and Evans 85. Evans, it seems, told Ventris and his schoolfellows something or other about the mysteries of Linear B 2. Whatever he said, Ventris discovered in that brief conversation his life’s direction. He would decipher this script. And perhaps not incidentally destroy (and, who knows?, release) this man, and shortly afterwards himself.

![]()

I always imagine that architects wash their hands to the elbows before and after work. Like surgeons or lawyers, architects are megalomaniacs, even if the gene lies dormant.

Architecture is a profession, not a calling. Whole schools of architecture exist which turn out thousands of architects every year, more than any civilisation could ever believe necessary, and yet I have never known a failed architect. Incompetent architects, but not failed architects.

The woman I knew in Venice, the lover who some years later nearly destroyed me, was just such an incompetent architect. She told me a story about her first job. She was freshly graduated and working for an architectural practice, and her first bit of work was to see to the removal of an internal wall in an apartment building. She consulted the original blue-prints and oversaw the removal of the wall, only to receive a call in the middle of the night from a structural engineer informing her that the ceiling was about to cave it. When she arrived on site it was sagging and groaning on giant metal legs. She double-checked her work and found that there had been numerous and substantial changes to the original plans over the years which meant that the wall in question was now load-bearing.

She told me this story, laughing at her own youthful twittery, the first night we went out together. I should have read it as an ugly threat, a confession of culpable negligence that might—in the event did—extend to the care she would take over our relationship as it too started to carry weight.

—twittery—

![]()

I don’t know much about football. Clarke knows more, and assures me that if I knew more myself I wouldn’t write about bronze-age spectacles and the Odyssey in the context of a football match. Just like the middle classes, he says; you have to justify it to yourself, or piss all over it, appropriate the territory. Next thing I’ll be writing about Greek theatre and the agon.

We can take it for granted, I think, that his comments about the twelfth man being the Pazzi chapel are ironic and at my expense.

My experience of football as a spectator is indeed limited.

My father, who used to work for GEC, designed the lighting scheme in the mid-1970s at Stamford Bridge and got a lot of free tickets on the back of it. I used to go along, a small boy, and watch second division matches—I remember watching games against Fulham, Huddersfield Town, Carlisle, Watford. The ground was half empty, and, with the running track around it, the pitch was distant. We sat in the director’s box, my father, pleased with himself, pointing out Eric Sykes or Richard Attenborough or Elton John; and I remember looking out from my vantage across the windblown terraces dotted by men in flat caps leaning on the steel crush barriers.

At Stamford Bridge I saw Bobby Moore and George Best play for Fulham against Chelsea, but don’t remember it. My father assured me many years later that Best was rubbish. I saw Butch Wilkins awarded the Young London Player of the Year trophy on the pitch before one match, and didn't think it strange that this young man was called Butch. It was the 1970s.

Since then I’ve only been to handful of games. It’s true what Clarke says, I don’t know an awful lot about football, but I know what the curious warmth, like a cattle shed, of a crowded stand in winter feels like; and I understand the transformation of the spectacle when the floodlights are on in the second half and there you all are, crowded into this one spot of light, like, well like Athenians at a performance of the Oresteia, barbarism or winter darkness held at bay for a moment by the agon being played out in front of you and around you.

![]()

This at any rate is the popular legend.

His name was Konrad Moscicki and in fact he spoke English perfectly, having been largely brought up in Merton where he and his father and brother had come to live before the outbreak of war. His father had been a high-school teacher in Poland, an intelligent and literate man, but in England he had worked as a house painter, a profession into which Konrad had followed him. Konrad was bilingual but taciturn. He played a bit of football up and down the south London and Surrey leagues, and had arrived at the end of his career—if you can call it a career—at Kingstonian.

You could hardly call Konrad an exile, but he had grown up in a exilic culture – a home where the intellectual and cultural life was sealed off and distinct from the life in the world outside. Every morning Konrad and his father and brother would step through their door and spend their day in that world, working, sitting in pubs and cafes; but they knew that at the end of each day they would retreat to a home that was on a remote plane of existence. Perhaps this is one adequate description of the Failed Life—a life of silent, shared exile, speaking a language no one credits you with knowing.

![]()

At the games there is still now a rump of old Norbiton fans who stand moodily around on the terraces like Soviet peasants at a May Day parade. Kelley typically comes and stands with them from half time and watches the second half with them in mute solidarity.

In the first half Kelley, if he turns up, is slumped in a corner of the director’s box; he exchanges a handful of words or a bantering nod with his fellow directors, is clearly charming to their wives, their guests; you can see Lloyd hopping up and down in his company, and you can see the tension between him and dell’Aquila, who they say is the real money in the club and certainly represents the old Kingstonian interest.

Kelley, oddly, seems only to tolerate football; in all the time I’ve known him (not very long), I’ve never heard him utter a word about the game. He stands and watches it as he might watch his dogs chase each other around the park.

![]()

Solomon’s library is located above Solomon’s bookshop, which can be found near the bottom of the predominantly residential streets between the Coombe Road and the Cambridge Road, nearer the Cambridge road than the Coombe Road. It has on one side of it a dry cleaner’s and general clothing repair shop. On the other side is a florist.

Solomon’s library and his bookshop are in fact one and the same concern. It would be perfectly possible for a member of the public to walk in, go up the stairs, pull a book off the shelves, take it downstairs and buy it, without ever realising that this had been the violation of a library.

However it rarely happens, largely because Solomon does not really want to sell anything. He opens his shop late and at irregular hours, sits at his roll-top desk in the back absorbed in what we now know to be his particular project. If you shuffle embarrassed up to him to pay your couple of pounds, he looks up at you as though through a dense fog, smiles wanly if he smiles at all. He has the cricket on the radio in the summer, quietly; in the winter occasionally some music, Monteverdi or Palestrina. Always on quietly.

He is descended, I now know, from Cochin Jews, but remotely, all sense of connection or belonging attenuated. He dresses carefully in old twill and polished brogues. If he is an exile, you think, then we are all exiles. And yet, he is an exile.

![]()

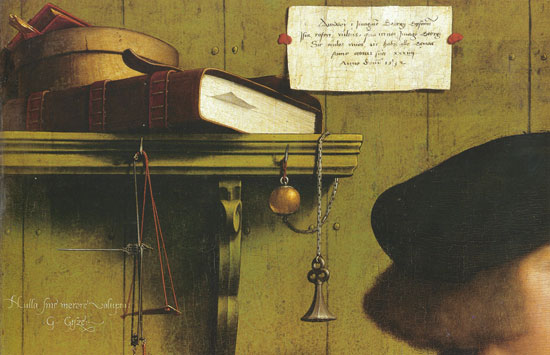

I use the contrast in this passage between the upstairs and the downstairs of Solomon’s bookshop as a sort of organising principle, but in truth it is no longer a merely interesting asymmetry but a practical problem.

Clarke brought me to Solomon’s library to talk about the possibility of locating our model of the Palladian North End there, but the proposal to make the library a locus of the various Norbiton projects became tied up, in this and subsequent conversations, with the more immediate and less clearly stated need to rescue Solomon’s shop from his own neglect.

When I talk of his shop as a space overwhelmed, it is in fact a foetid cornucopia of unsorted books. People bring them in from time to time (not so often now: old books mostly go to charity shops) and he pays them whatever they judge fair and stuffs the books, unexamined, into whatever cardboard box is nearest. Customers in turn are forced to go through these boxes and make Solomon an offer for anything they want. It is not a bookshop anymore, but a space in which the clearing of books takes place.

Solomon talks glumly of shutting down. He is at or past retirement age, and he can no longer cope with it. In the morning when he opens up he darts as quickly as he is able in between the toppling boxes of books and secretes himself in the back office where he frets over more immediate and tractable problems of emendation, keeping the shop at a mental remove for as much of his day as he can.

But I encourage him to continue, to put it right. Or rather, if he wants to shut up shop and retire then he should, but he should put it in order first, wind it down like a good administrator. I argue that the library is generated from the lump or mass down below. It is a system, a machine.

—put it in order—

– Portrait of Georg Gisze

Hans Holbein

We therefore agree that I will contribute some of my time—a couple of afternoons a week—to setting it all in some sort of order for him. I look forward to running increasingly fine filters over the stock, chucking some out, gifting others to charity shops, shrinking the rest gradually into the shelves; perhaps I will set up an online inventory of the best books, rationalise the taxonomy, alphabetise the stock, introduce some sort of grading by height. I can imagine the tidy-minded pleasure of selling a book and filling the gap on the shelf with something from the piles on the floor.

In recompense for my time I will have the use of Solomon's van—an old Mark V transit—for the couple of gardening jobs I have by now picked up.

![]()

Walking is the surest antidote to tedium. I am never bored when I walk. Or I’m bored in a different way.

Tedium is a function of stasis, broadly speaking. It is a suffocation of the soul through silting.

The poet Edward FitzGerald (1809-1883), translator of the Rubaiyat of Omar Kayyam, had a privileged and peculiar upbringing in which he and his sister were frequently left to their own devices, hour after hour, two small children in a large house in Suffolk.

There was nothing to do. In some memoir, he relates (if my memory serves) that he would lie in the middle of the floor of their playroom and bellow like a bull for pure tedium. They would spend hours sitting at the window looking out at the unchanging country, waiting for something to happen. Nothing ever did.

—tedium—

– Grave of Edward FitzGerald, Church of St Michael & All Angels, Boulge, Suffolk, England

Photo: Cameron Self (Own work by the original uploader) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

My own adolescence was marked by a similar rhythm. The school I went to was a sort of inverse panopticon, where the indifference to what you did in the long off-hours somehow managed to exert an invisible control over you—as though licence were the surest and most Jesuitical route to boredom, to bellowing frustration, hence to docility, and to devotion.

Whether that was the intention or the established habit, or even just a beneficial side-effect of the accumulated crises of the teaching staff, it partly worked and partly misfired. My resistance, such as it was, was always of the sullen variety. But at seventeen, eighteen you shouldn’t be stuck in a silent cold room with your overcoat on and the window panes rattling, reading Emma.

Little wonder that I hyper-vividly recall the intense blur of incomprehension on my last school day—a day in early June—confronted as I suddenly was by that Serengeti of freedom, so long concealed from me, and otherwise known as The World.

![]()

Shell has its headquarters (or part of them) on the South Bank of the Thames next to Waterloo Station in the Shell Centre. The Shell Centre was designed in the late 50s and built in 1961.

—upstream, downstream—

– Shell Centre, London

By The original uploader was Blueshade at English Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Parts of the Shell Centre are known (or were, in Hunter Sidney’s time) as the upstream and downstream buildings. They were so named according to which side of the Hungerford Bridge they fell on (the distinction was inherited from the Festival of Britain site, on which the Shell Centre was constructed; the Downstream building is no longer part of the complex) but Shell, like all other petroleum companies, uses upstream/downstream to categorise its business, with upstream referring to the drilling and extraction operations, for example, and downstream to, say, marketing and distribution.

Upstream/downstream thus has a mild polyvalency in World of Shell, and Hunter Sidney adds some colour to the metaphor, joking tiredly that most of his career was spent paddling and then drifting in the sludge of the downstream creeks and shallows. Very peaceful, he says.

![]()

The Anti-Literature is Hunter Sidney’s term for a collective literary project, or series of literary projects, under way in the deep net. It is a story, or nest of stories, that multiplies, not endlessly or without control or conclusion, but nevertheless iteratively, copiously, and conditionally.

Hunter Sidney’s own particular zone is an if-story, called The Love Filter, where the reader can choose to pursue one or other of a range of bifurcating storylines; some of the bifurcations are invisible, activated by links followed or not followed, which catapult or do not catapult the reader into mirror sites which appear identical but are not.

The controlling narrative of The Love Filter is a detective story, where a sort of roving ur-detective is investigating a series of crimes or absences linked to an underground organisation or dating agency (it is not clear to me which) in which highly-vetted, monk-like associates are presented with a list of what we might call ideal lovers, but which The Love Filter calls scintillations—the idea here is that the ideal other we crave has been shattered at some early point in the universe and dispersed in ever-recurring patterns through the world. It is the goal of each devotee to reassemble that desired, endlessly researched other by tracking down and in some way interacting with these 'scintillations' or reflections or refractions of it: some old, some young, some male, some female, and so on. There is some religious or anyway self-fulfilling end in sight. There is a lot of sex. Desperate possessiveness. No little disappointment. Hence crime.

The detective, who, I should say, is of variable sex and sexual orientation, is sucked into this highly-determined substratum, and from what I can make out is presented with his/her own list. The pursuit, if we can call it that, is studded with crimes and confessions and retributions and revelations. The characters—many of whom are reassembling their own other—become in the context of this vast de-cultured saga like gods or heroes with multi-linear histories and competing aetiologies which are similarly transformed, in the vastness of the work, into myth or rumour floating in from 1000 or 10000 rooms away.

Needless to say, The Love Filter, with its textual, tonal unevenness (whole tracts of it are a bit crap), its contradictions, its inconsistencies, its unreadableness, enacts its own central truth: that we are each of us not a recoverable essence but an ensemble, and in turn a mere fragment or facet to those who know us; and we are each ourselves confronted therefore with a world of seductive but un-piece-togetherable fragments. Life, it says, is a puzzle so dissolute it ceases to be a puzzle, becomes a mere incomplete set of puzzle pieces. Knowing this gives you the liberty to cease reassembling, and this is the beginning of The Failed Life.

—a puzzle so dissolute—

– The Procession to Calvary

Pieter Breugel the Elder

![]()

In this context an object of knowledge might be something like love, or betrayal, or conflict or memory; or a given political situation, or a sexual or psychological dynamic—whatever, in short, the writer believes him or herself to be writing ‘about’.

Hunter Sidney is suggesting that what writers are attempting is not in fact a clear view of an object of knowledge at all, but the construction of a machine (a novel, a series of essays, a poem) to harness that object’s (suggestive, dialectical, culturally familiar) power.

In Star Trek: Voyager, the crew first make contact with the Federation back in the Alpha Quadrant via a vast relay of transmission stations created by an ancient civilisation; each of these relay stations is powered by a tiny (1 cm) singularity at its centre. Someone has harnessed a black hole.

This is, rather loosely, how I imagine All World Literature to work.

![]()

Clarke is as usual impatient of my analysis, if I can call it that, of double-entry bookkeeping in terms of Rational Ideas, saying John Locke kicked down that rotten door centuries ago.

Bureaucracy, he notes, quoting Marx, supports the prevailing power system and is frequently the source of the greatest inertia within that system.

Administration slides towards the evil of bureaucracy the more permanent it becomes. Thus far we agree.

Where we start to diverge is the connection he thinks he notices between the codification of double-entry bookkeeping on the one hand, and the inception of the evil cinquecento on the other. He argues that what had been a loose and amenable practice in Florence for centuries became in the age of print a bureaucrat’s weapon.

I concede the possibility—or more frankly I can’t be bothered to argue—that codified double-entry bookkeeping grew out of and started to service the growing size of the capital economy; it provides an informational skeleton for the big capital generating or utilising machines (company, state and so on) which are starting to emerge at about this time.

And it is also true that the quattrocento (city state, Masaccio) is good and the cinquecento (Papacy, Empire, Michelangelo) is evil and corrupt, so he has a (highly rhetorical) point. There is a case to be made, taking shelter for a moment from Clarke’s thundering discourse, that quattrocento Florence is fundamentally a medieval society, and cinquecento Florence, or Italy, is fundamentally a modern one; but that some of the analytical tools of the modern world—Linear Perspective, double-entry bookkeeping, America (just) happen to have been available to the quattrocento.

What we have in the quattrocento, therefore, or bits of it (Masaccio, Donatello, Brunelleschi) is a peculiarly felicitous point of balance, or set of virtues, about to tip over and down the rabbit hole of history, at the provisional bottom of which Clarke like a blacksmith of the mind now argues the finer points of their existence with a lump hammer ad infinitum and ad nauseam.

![]()

In much the same way, I suppose, as physicists handle the interactions of matter and energy through mathematical objects, as it were by proxy. However, I'm extrapolating this supposition from something I think I heard a physicist say on the radio some years ago: that you don't understand quantum mechanics, you just get used to it.

I would apologise therefore for being way out of my depth, as in fact I am, if it weren’t for my suspicion that imaginative accounts of the sort I’m proposing have none—no depth, that is: they define their own terms, beyond which there is simply nothing – they are not constrained by inconvenient external referents, such as, for example, a universe.

![]()

To be clear, for create I do not intend summon from nothing.

The beginnings of surplus capital can be traced from such diverse phenomena as the division of labour or the codification of property rights. Accountancy practice does not bring the capital into being so much as summon it from latency, give it shape, present it for manipulation. Its availability to merchants or bankers (tellingly, much the same thing in quattrocento Florence) is heavily dependent on standardised forms of recording and presenting its movement, its characteristics; it can then be manipulated, transferred.

![]()

Von Humboldt, in his voyage to the watershed of the Orinoco and the Amazon and his tracing of the Casiquiare which joins them, mapped, as he went, not the unknowable jungle, but his own footsteps.

He followed the river and recorded the position of small missionary stations or trading posts as he went. In May 1800 he and his travelling companions reached Esmeralda, last Christian settlement on the Orinoco. It was little more than a few huts, 'home' in the words of Laura Dassow Walls, 'to a few score Indians, zambos, mulattoes, banished soldiers and exiled monks'.

Humboldt marked it on his map. In 1958, two botanists who retraced Humboldt's route found no sign of the place: it had been sucked back into the jungle, effaced, reclaimed, 'although it is still to be found on every modern map'.

You never know, looking at a map, where the past of it begins and ends, where a bit of coast has fallen into the sea, a hamlet vanished into the jungle, or a road now become part of a one-way system.

![]()

Emmet Lloyd's fortune, I now know, is derived from a family nursery business. Nursery as in plants. Half the nurseries in South London, it seems, are owned by the Lloyds.

Emmet passes on occasion through the business like a comet on an irregular orbit, his arrival greeted like a harbinger of great evil, but his actual presence making, in fact, very little difference.

For a number of years it has been his chief objective to 'go technological' and he has employed a number of software engineers to create a searchable database of all plants (whether all of Lloyd's plants or all plants full stop is not clear to me). Each of these software engineers has left in different circumstances; but given that the database is to be cladistic rather than Linnaean, fully searchable also with image-matching capability, and, the latest notion, user-led (whatever that means—a sort of plant wiki, perhaps?), there is doubtless some correlation between the upward spiral of the specification, and the downward spiral of the engineers.

I confess it seems an interesting project.

—item: bromeliad—

– A Pineapple

Jacopo Ligozzi

![]()

Clarke, who does not properly understand it, regards it as a meretricious trick; he says that there is no mystery to it, it is not a symbolical form (his expression); he does not understand the maths, as I do not, cannot remember his art school arguments, but he is confident they refute it.

To be clear, by linear perspective I understand something done with an Albertian insistence on straight lines. The back end of a horse, no matter how well executed the foreshortening, is not linear perspective.

Thus:

—Full Alberti—

– Flagellation

Piero della Francesca

—Back End of a Horse—

– Battle of San Romano

Paolo Uccello

Having said which, it is only fair to point out that some of the lances in the Uccello have fallen at right angles to the picture plane and to each other. A sort of degraded perspective grid is down there somewhere.

![]()

Erwin Panofsky, the great theoretician of linear perspective, argues that perspective is a symbolic form, a neo-Kantian term (derived from Ernst Cassirer) for a ‘form of knowledge’, which in turn is a representation or structure or frame that stands between the viewer and the world and allows the former to ‘both make and obtain’ knowledge about the latter.

Examples of symbolic forms, for Cassirer, include language, myth, science.

Panofsky’s description of the pictorial space in linear perspective as infinite is not, so far as I can make out, a mathematical assertion; he merely intends that the pictorial space is imaginatively extensible in any direction beyond the plane: we see but a slice of it. This distinguishes it from those medieval paintings of the whole Choir of Heaven ranged in order, from where there is nowhere to go.

—nowhere to go—

– Choir of Heaven

Fra Angelico

![]()

Not to mention the forms of religious observance, in which we capture our gods.

Chakotay, for example, the Native American New Age mystic first officer of Star Trek: Voyager, no longer takes peyote to kick-start his dream quests—he has a medicine bundle containing various hoodoo rocks and sticks, and a hyper-technical 24th-century bit of apparatus which provides a more controlled, possibly more mellow, hallucinogenic stimulus. When his crewmates accuse him of being ‘a spiritual man’, he modestly concurs. In his trances he converses with his spirit guide, a timber wolf, and encourages Janeway to encounter her own (a lizard?).

I attended a Roman Catholic secondary school where we were annually invited to venerate the relic of our titular saint, a fibia or tibia or leg bone of some sort, which was contained in a glass tube resembling a piece of apparatus from the chemistry labs. We venerated the relic to the talismanic drone of the school hymn, a dreary 40 verse epic in Latin, O beate me, Edmundo!, which was studiously copyedited by generations of schoolboys to O beat me Edmund! in every hymnal; it didn’t scan but we would attempt to sing it anyway. It was just a moment of resistance, a last clutch at a mouthful of air, after which the oceanic hymn dragged us to the bottom; and so we mumbled and sang and processed like wraiths of the deep to the side chapel and kissed the glass tube; an altar boy (hirsuit young greaser, typically) would wipe each boy’s slaver off with a cloth. There was incense and hyper-vigilant surveillance as teachers and prefects nervously marshalled this departure from the well-oiled routines of control. We processed, then, with the docility, not of a devout cloister, but of a prison yard: this was all a bit of a change before we returned to breaking rocks.

I would very much like violently to upbraid my young self, shuffling along in that insane procession, this is the 1980s. Just walk out of there. You don't have to do this. But that young self, arrogant, complaisant, on the inevitable road to Grand Failure, would not, in the best tradition, have heard a word.

—upbraid my young self—

– John Knox Upbraiding Mary, Queen of Scots

William Powell Frith

![]()

By Francis Yates, for example, who was certainly no art historian. Botticelli was working within a context of iconographical or symbolical representation where it was not a great leap from saints with their attributes to pagan gods doing funny stuff in a garden; and while Botticelli was an intense young man who would later chuck examples of his work (so the story goes) on to Savonarola’s bonfires of the vanities, it does not necessarily follow that what he was doing here was making a magical object.

![]()

Clarke relates that when he was in Rome his girlfriend the artist had, on her kitchen wall, a number of postcards of paintings which she had collected over the years, cramming, in that demotic way of postcards, vast canvases or frescoed walls or sculpted peach stones or miniature ivories into the same format, as though in these latter days we had finally lighted on a golden aspect ratio.

Clarke doesn’t recall what the individual painting were, but she liked Titian and Veronese, Rubens and Velazquez; Caravaggio, Stubbs, Turner, Ingres. And he says that once or twice she wondered aloud to him what the connection was between them all.

—wondered aloud—

– Louise-Albertine, vicomtesse de Haussonville

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

There must be some common factor, she speculated, which prompted her to take these particular cards down and post them back up again in every house in which she lived. Not something deep, necessarily, perhaps something superficial, some tickling of the eye, some particularity of hue or form. But there was something, she was sure of it. Some pattern to all this, which she could perhaps hope one day to learn to read: it could be that the key to her life’s work, her struggle to understand the world in paint, was staring at her day after day on her kitchen wall. She might be able to harness it. To take an audacious short cut and end up somewhere remarkable.

Clarke says he tried his best, for her own sake, to piss on her bonfire. He volunteered that the cards had a history – she had bought this one here, that one there; there was no pattern to her trips, so there was no pattern to the cards on her wall.

This made her simultaneously sorrowful and disproportionately angry, as though the two of them were locked into some drama of conversion, and he was dumbly resisting the little glints of salvation she was showing him.

She was engaged, Clarke realises now, in a form of sympathetic magic, insofar as magic overlaps with psychology. Arranging and rearranging familiar objects, furniture; cleaning, gardening. It was a way not only of reading the world, recording the traces of your interactions with it, but a way of taking control of it.

He himself has postcards on his wall, or stuck to his fridge with Grand Canyon magnets; objects that he values, that would be impossible for anyone else to understand. He spends time now thinking about the connections. He says that his point about the contingency of his girlfriend’s having picked up postcards here and there was an irrelevance; her life was anyway a contingent pattern: you worked with what you had. And it was she, in the end, who had bent these disparate objects into an orbital geometry.

No, there was something here worth pondering. The artist was right, but not in the way she thought. There is a connection, but the underlying topology is complex, polycentric; some of the data is corrupt, meaningless. There is no tracing of connections, no isolating of commonality; only an onward pondering, and a retrograde remembering.

![]()

Such is money. Banking was a relatively new technology of which the Medici were masters; the Sforza, with their great caparisoned horses and blunt bludgeoning swords, their condottiere master, belonged to a passing age. And so the Castello Sforzesco, if memory serves, is a bloated and scruffy enclosure; one which might be in need of a little formal circumambulating, a little psychological topiary, of its own.

—bloated and scruffy—

– Castello Sforzescso, Milan

Photo: I, Sailko [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

Having said which, I should confess that I play a little fast and loose here with my chronology. The Medici chapel was painted some months after the visit of Pius and his guests, presumably after the departure of the young Sforza, and certainly before he was greeted in the chapel.

But the point stands. What is a few months in the vast history of human ritual and power? If we go, once again, a little widdershins, a little nomad, and conjure thereby some true if slightly shimmering effect from the morass of events, who can object?

![]()

Tony isn’t really a duke. He is a wealthy businessman, semi-retired. He ran a firm of builders and had his commercial finger in a lot of concerns, locally. He and I are going to contract for some work on his garden. I come, evidently, highly recommended – by Kelley or his wife, I don’t know which.

His commercial base is in Kingston but he lives now in Richmond, an expensively dull suburb of London on the other side of the park, far beyond the gravitational reach of Norbiton. I am driving Old Sol’s Mark V Transit. They don’t allow commercial vehicles through the park, so we are going around. It is a day of convalescent sun somewhere on the margins of winter and spring, a mid-week morning, I don’t recall which day. We are—I am—moderately excited because we are driving circuitously away from Norbiton. Neither of us gets out much these days.

Norbiton is an Ideal City, with all that that implies of civic virtue and civilisation, the commerce of great spirits; Kingston is an empirically real town, with all that that implies of trade and pigs-to-market. Perhaps it pleases me to think of Kingston as sweating under the yoke of an in-bred aristocrat, but the truth is dell’Aquila is a poor immigrant made good. And most of Kingston doesn’t really know he exists.

![]()

I don’t know why, perhaps because of his ongoing, almost comfortable feud with Kelley. Clarke relates that it was dell’Aquila who orchestrated the takeover of Norbiton FC by Kingstonian. dell’Aquila was the owner of Kingstonian, as of so much in Kingston, and at the time they played on an insubstantial tract of mud out on the Richmond Road somewhere. It seems he saw the extraordinary Palladian North End go up across town, coveted not the stand, but the space, the planning permission (which had been contravened, as he no doubt discovered, in many respects), waited for a moment of vulnerability in Kelley to develop—lack of liquidity, specifically, coupled with building regulation inspections—and rapidly orchestrated the takeover of the whole club and the Recreation Ground.

Kelley didn’t really know what hit him. Where Kelley’s power is monolithic, conspicuous, vulnerable, dell’Aquila’s is tentacular; it is rooted in his building firm, but he owns by all accounts a lot of property throughout Kingston, and has stakes in other businesses.

Back in the 1980s he suddenly and briefly emerged, like a properly menacing Gatsby, from the shadows. He was a major investor in the creation of the Bentall Centre, and now sat—in his capacity as town councillor—on the planning committees which oversaw the Leonardesque diversion of the London Road from its natural course, and the consequent pedestrianisation of Kingston Town Centre. As a fluorescence it was more low-pressure sodium than Florentine, but it brought about its transformation, none the less.

He is now retired or semi-retired. He makes an appearance at the football once in a while, perhaps to stimulate fading memories of dusty kickabouts in the bombed out streets of Salerno with the other malnourished post-war kids, heads shaven against the lice, as wiry and able and dangerous with a football at their feet as they were in life.

Or perhaps not. Perhaps he is just keeping the sympathies and resonances of his network, his sphere of possession, alive, out of habit, against a rainy day.

![]()

A bonded servant made 7 ducats per year. The richest merchants in Florence (the Medici, the Strozzi, the Rucellai) would do well to generate annual revenue (not profit) of 20,000 ducats. The alum mines at Tolfa generated around 50,000 ducats in 1480-81 for Pope Sixtus IV, whose annualised income has been estimated at around 290,000 ducats. In the reign of Clement VII, Michelangelo suggested in a letter that his services to the Pope should be valued at a rate of 15 ducats per month; this was taken to be a ludicrously low estimate, and the figure of 50 per month plus expenses was mentioned.

I think a ducat might more or less equal to a florin. Who knows?

![]()

Federico was injured by a sword blow in a joust at some point after 1450, and lost his right eye and the bridge of his nose. That side of his face was monstrously scarred, by all accounts—he was typically portrayed thereafter in left-profile, although this is also a convention of medallion-portraits in the quattrocento, and there is one painting of him—in triumph, by Piero della Francesca, in which he appears in right-profile.

—right-profile—

– Triumph of Federico da Montefeltro

Piero della Francesca

For all their modern drives and classical sensibility, there remained in the princes and merchant aristocracy of the Renaissance a weakness for medieval chivalric trappings. Martial games had their classical lineage, into which the joust or tournament fitted. In the giostra at Santa Croce of 1469, won, not surprisingly, by the young Lorenzo the Magnificent, the youth of the ottimati paraded to the piazza Santa Croce with their retinues done up in their finest medievals; Lorenzo’s banner, possibly painted by Andrea del Verrocchio (who was responsible for the apparato of the entourage and Lorenzo himself), involved a complicated representation of a female figure standing next to a laurel with all its branches withered bar one, which she was busy weaving into crowns; this was accompanied by the Old French motto le tems revient.

Descriptions of the event are thick with brocades, damsels and fleurs de lys; but Lorenzo’s horse was adorned with a ‘classical’ breastplate, and I am moved to wonder if the time renewed was any particular time, or a mis-remembered jumble of all time, like some post-apocalyptic Mad Max version of history.

Gifts of ceremonial armour were commonplace in the quattrocento: following his triumphant campaign against Volterra, Federico da Montefeltro received an enamelled and gilded silver helmet designed and produced by Antonio del Pollaiuolo, bearing the emblem of a griffin (arms of Volterra) being subdued by Hercules (iconographically associated with Florence). The helmet is now lost, but was much discussed in the literary accounts of Urbino3.

No doubt the gnarly Duke (per poco non dimezzato) felt a throb of sympathetic pain as he took possession of the ludicrous object.

Perhaps Minotaur is a touch strong, but I don’t think you would want to stumble in on Federico in his studiolo and catch him in a sulk.

![]()

Actually I may be conflating Hunter Sidney’s position with that of Civ Clarke, who has independently volunteered that marriage is a violent or coercive institution. I paraphrase his argument as follows:

In all other contracts, explicit and implicit, the extent of the agreement is limited in scope. We do not contract ourselves into slavery. We agree to do this or that for this or that amount of time; but the agreement extends no further. If we are to identify a virtue in the disposition of contract in total contract space, it is precisely in this limited extent, which allows, among other things, for a flow in the system—as one contract expires, others come into being, and so on.

Marriage on the other hand—the modern Western form of it—demands total surrender. You do not limit the extent of its influence on your life in any way. All behaviours, desires, actions, inactions, hesitancies, inadequacies are provisionally entailed. You can never say about anything in the context of your marriage, this is not relevant. This is relevant only to me. You could argue further—and Clarke does not hesitate to do so—that not even the responsibilities entailed in parenthood, or running a corporation or a country or an army, are of this insane and formless nature. The contract of parenthood, to take one example, is implicitly structured around a series of sub-clauses under which the parent is expected to relinquish responsibility over time. Heads of corporations can delegate, take time off. When they are lying in the bath listening to Mozart drinking gin and recalling dimly the dreams of their youth, they are no longer the President of the Corporation. They are something else. But they are still married. All good will which might subsist between two individuals is necessarily exhausted in the limitless emotional subsections of the marriage contract.

Clarke isn't married but he has a girlfriend, Mandy. I wonder if he reasons to her in this vein.

The universal vigilance of the marriage contract works on us like an emotional panopticon, Clarke assures me. It renders us docile, and as Foucault explained, docility is a condition of control.

I should point out that panopticon, pronounced 'panoctogon', is also Clarke's nickname for his own towertop flat. Make of that what you will.

![]()

Forzieri are sometimes inaccurately called cassoni. The term cassone did not appear until the cinquecento, and even then did not denote the bridal chest. Forziere denotes a strong box, locked with a key. Draw your own conclusions.

In the sala degli angeli in Urbino, just over your left shoulder as you stand in front of the Ideal City, is this object:

—strong box, locked with a key—

On the assumption that it is a forziere rather than a cassone, it pleases me to think that someone else conceived of marriage as a reconfiguration of space.

![]()

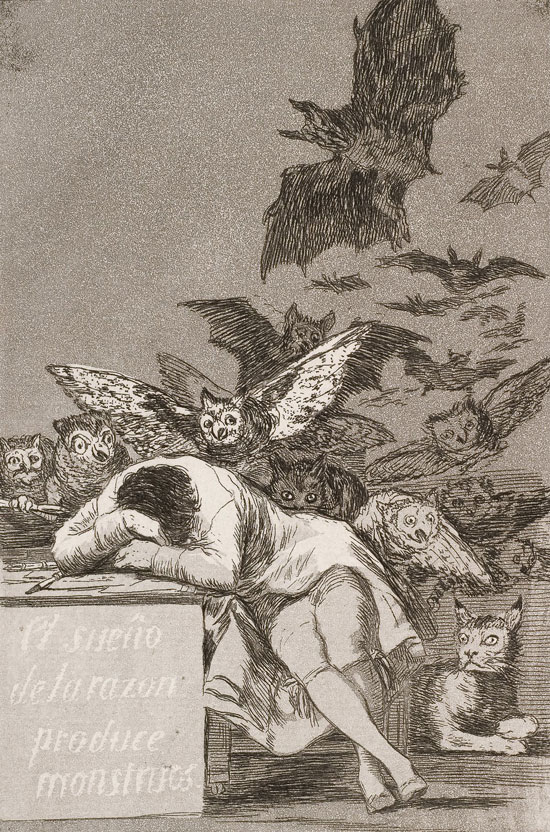

I recall reading in Raymond Chandler’s letters that much as he felt an impulse to write during his insomniac nights, he could rarely use anything that he wrote when he came to re-read it. It was always tinctured by fevered exaggeration. It was monstrous prose. At night you are hyper-alert, he concluded, to the presence of the beast, whatever it is that predates upon you, creeping around the diminished ring of firelight. For this reason he used the time to write his fanciful letters.

I do not know if he considered the reverse possibility: that by night, having less in view to distract the inner eye, you more accurately perceive both the texture and lineaments of the condition of your life, the apparent exaggeration being no more than the surprise of disclosure, the lurid flash of clarity.

Perhaps, had he written his novels by night, he might have crystalised the genre of night-novels: that is, novels to be read only at night, under the arc-light of full self-awareness.

—arc-light of full self-awareness—

– The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

Francisco Goya

![]()

The routines were not complex, quite the contrary, but they centred on the fact that this was the only time of the day that he could read anything. Reading was the fulcrum of the routine, allowing him, for a moment, the balm of other voices in his head. He would sit by a window, open depending on the season, drink tea and read his morning book.

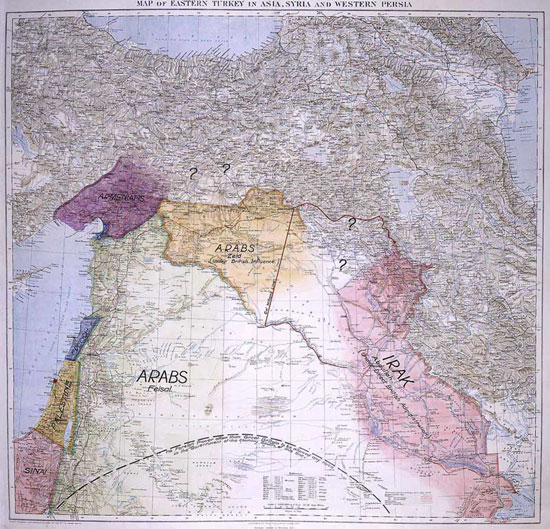

The only book he recalls reading in this period was Seven Pillars of Wisdom, the whole interest of which, claims Hunter Sidney, lies in the interplay between on the one hand Lawrence’s manic attempts to goad the (by his account moody, contemplative, volatile) Arab nation into self-determining life, and on the other his own tendency to melancholy reflection, self-recrimination and inaction.

Lawrence claimed that the title of the book had nothing to do with its content, but derived from a juvenile novel concerning seven cities, which he carried over for sentimental reasons. It is taken from the book of Proverbs: (ix. I) ‘Wisdom hath builded a house: she hath hewn out her seven pillars.’

Hunter Sidney, perhaps spurred by his own melancholy restlessness at this time, claims that the title is in fact pertinent. That wisdom might lie neither in action nor in inaction but in some ugly juncture between the two struck him, as he sat at his window, book on his lap, looking out at the world, as by turns a depressing or energising quandary; one which he claims never have resolved to his satisfaction.

—never satisfactorily resolved—

– Map presented by Lawrence to the Eastern Committee of the War Cabinet in November 1918

![]()

The discussion of habit with Mrs Isobel Easter took place over two or more conversations held in her garden in the early spring. Typically in that period she would bring me tea shortly after I arrived and thereafter every hour or so, swapping my old cup for a fresh one. Sometimes she would then stop and chat, sometimes not.

If I recall, it was a discussion on the nature of gardening work, conforming as it seems to do to a routine of pottering maintenance interspersed by moments of more violent contraction (uprooting a bramble bush) or innovation (planting, or as I am learning to distinguish, sewing something), which led to our discussion of habit and routine in general. On some days I leant conversationally on my spade more than I wielded it, but I took this to be an aspect of the tacit job description—the garden was a limb of Mrs Isobel Easter’s sphere of possession as much as it was of mine, and the dialogues were a form of ritual parlay at the boundary, or intersection; we were like two Papua New Guineans comparing kinship rosters to see whether they need to try to kill and eat each other.

![]()

By, I suppose, ‘the forces at the heart of existence’ whatever they may be; I hesitate to point out that in a gravitational system each distinct body will exert its own contrary pull; I think I would prefer to test the hypothesis that a life is a series of actions or inactions connected by their own internal, mutually interfering and reinforcing logic; like a Buckminster Fuller tensegrity structure.

—mutually interfering and reinforcing logic—

– Skylon, Festival of Britain, 1951

Hidalgo Moya, Philip Powell and Felix Samuely

I don’t think of saying this until later on, in the pub, when it is too late. Mrs Isobel Easter does not drink in pubs.

I would counter-observe (against my own hypothesis) that when Thomas Browne in the Religio Medici (1642) notes that ‘age doth not rectify, but incurvate our natures, turning bad dispositions into worser habits, and (like diseases) brings on incurable vices’ he seems to be supposing the pre-existence of a disposition which is then reinforced by habitual action. I concede that this has the merit of intuitive simplicity.

![]()

I know of a man who developed the habit, in early retirement, of eating curry for lunch and curry for dinner, in the same curry house, every day. He ate a lot of curry, and drank a lot of beer, and was dead at the end of a year.

If death by curry was his object, as it seems to have been, can we say that he had established for himself a routine? I don’t know. I suppose there is no reason why a routine could not be tinctured by destructive anxiety, just as so many of our habits are. I think it matters, though, whether he sat at his table in the curry house awash with guilt and sadness at the satisfaction he was taking at gorging himself, at the pain he was causing his wife, at the amusement he was giving the waiters; or whether he positively enjoyed playing out an endgame of sublime absurdity, relished his food, mused on the vicissitudes of life as he chewed his lamb tikka jaafrezi, took another sip of Cobra, lit a Rothmans between courses; folded his newspaper under his arm and strolled home in the mid-afternoon, suffused with well being. It matters, because the routine is managed not only in relation to some end, but also in relation to some here-and-now, insofar as the here-and-now and the end are linked. The here-and-now, to put it differently, might very well be the end.

When he died, his curry house catered the funeral, and I like to think that his wife, who presumably made the arrangements, knew what she was doing.

![]()

The Kelley garden, as described elsewhere, appears at first glance to be organised as a space of carnivalesque licence, stuff growing pretty much where and how it likes. It is founded, however, on a strong general architecture (admittedly only partially visible now, like medieval field systems seen from the air, or the stones of lost cities rising from the jungle); and from time to time over the years hands other than my own have been turned to the task of restraining its fecund baroque: beds have been restored, trees lopped, undergrowth cleared. Here and there, now and then.

A case in point is the bramble bush which runs along a part of the stone wall on the lower right of the garden as you descend from the house. Someone at some point, you infer it must have earmarked it for benign neglect, offering as it does a little natural play, some berries in season. A wild margin. I do not know that the someone in question was Isobel Kelley – as I do not know how far the garden is (as I like to think) a raggedy palimpsest of her struggles over the years with her husband – but I like to entertain the mental picture of her, a feigning sleeping beauty awake and silently patrolling the inside of her aggressive thorn hedge, picking the odd berry as she goes.

Civ Clarke, however, points out that I infer incorrectly. He knows, he says, for a fact that the bush has, on at least one occasion, been summarily dealt with. He was there. As was Kelly’s wife, Mrs Isobel Easter. As was a younger, more energetic Hunter Sidney.

It was a morning, he recounts, in Spring, when both Hunter Sidney’s love and the bramble hedge itself were yet to blossom; but there they were, will Kelley also, ripping out the whole bush.

It was a day’s work. They had first of all to cut the bush back to the root which, since the rambling thorn had infiltrated other more virtuous plants, was a job better done with secateurs and gloves than the hedge trimmer which Kelley produced. The lopped tentacles had then to be dragged out and cut up, adhering to and occasionally penetrating their stout-seeming gloves, stamped into bins and carried out through the small gate in the far back wall to the van. The exposed roots were then dug out, to begin with a surprisingly easy job, growing somewhat tougher as they approached the plant’s inner citadel, and finally near impossible as the roots delved under the wall itself, as though into some last underground redoubt.

Towards evening – in Clarke’s breathless retelling – Kelley moved in for the kill. There was a last litter of leaves and scraps of bramble lying over the grass behind them, the newly bared dank earth in front was churned up like some medieval battlefield under the clodded boots of heavy men; Kelley’s greyhounds – ancient precursors to the current springing pair – were lying some yards back, watching the weary activity of their master with the bureaucratic impassivity of a pair of diabolical sentinels. Clarke and Hunter Sidne were leaning on their tools.

Clarke says he had suggested pouring poison of some sort on what remained of the root, but Kelley seemed determined to finish it off by hand, and was on his knees, sweating and swearing, alternately digging and hacking with the spade and reaching into the hole and wrestling the stump back and forth, when his wife came out with cups of tea for the three of them. She had been doing this regularly all day, but this time she brought also a cup for herself, and she and Clarke and Hunter Sidney stood around for a minute or so in silence, cups of tea in their hands, in the cooling air and under a reddening sky; no one said anything and Clarke says he was moved briefly to take in the whole scene – the mud, the dogs, the gloaming, himself no doubt looming white and appalling like a tuberous god come to witness an act of propitiation on the part of Kelley – (in my imagination the scene has about it something of the Primavera re-imagined by Bruegel).

But then after a minute Mrs Kelley said, under her breath, Jesus, he'll give himself a hernia for the sake a giant turnip he's got in his head; Kelley, Clarke relates, turned and smiled, wiping mud over his forehead. He stood up and took his tea from the grass where she had put it, and Hunter Sidney, as though he had been waiting all day, all his life even, for this moment, stepped forward, stooped his frail-looking but, as it turned out, surprisingly wiry arm into the hole, and pulled and wrenched as though he had his hand around the vitals of the garden itself.

The struggle wavered this way and that, and then, with a final barely-audible but clearly chthonic imprecation and an answering dull snap the hero's arm emerged from the hole with a fragment of thick root; in the gloom he chucked it to one side (one of the dogs got up, stretched, and went over to investigate) and stood peering into the hole; he might have been waiting, says Clarke, to see if devils were going to pour forth.

Behind him, Kelley made a joke about his own inadequacy, but Mrs Isobel Easter (this, in Clarke’s estimation) just stared in mute admiration.

That Hunter Sidney could have seduced Mrs Isobel Easter by a display of superior strength is clearly a fanciful simplification of Clarke’s. But something about that day was fixed forever in Hunter Sidney’s erotic imagination, else why this tattoo, why the mandrake?

![]()

The enclosed private garden, as opposed to the cloister garden for example, is in medieval and other literatures a locus aptissimus for love: the pursuit of love and the act of love. The right place. In particular the enclosed garden, the hortus conclusus, the flower garden, the rose garden. Little wonder that Gabriel traps his Virgin in a hortus conclusus when he makes his pandering annunciation.

The sensory divagation or if you prefer dispersal to be had in a garden is a forerunner or complement to the sensory divagations implicit in the act of love. It is moreover intimate and exposed, public because in the open and private because separated off. And it is, finally, opulent—both in terms of actual wealth in medieval society, which is a sufficient stimulus in itself, and it terms of the leisure which that wealth affords.