Circumambulatory

—spatial infraction—

– Procession of the Magi

Benozzo Gozzoli

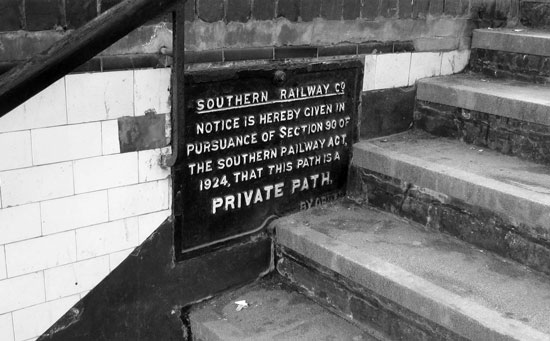

The logic of Norbiton’s streets has nothing to do with its circumference. Their grain is governed by the line of the railway, the routes into Kingston and Wimbledon. If you try to walk its perimeter you are forcing that grain, committing a minor spatial infraction.

—infraction—

– Norbiton Station

The same can be said of the streets of its interior: they do not lead to other places within Norbiton, but originate and terminate outside it. Their business is not with Norbiton, but across it.

When we walk the circumference of Norbiton, then, we do so as engineers of ideal space armed only with the string and sticks, the ambulatory measure, of our minds; we are engaged in the survey of the anfractuous, perhaps not properly existent fringe of an object which is only now coming into being: Norbiton: Ideal City. By plotting its rational limits, by walking its boundaries, we hope to conjour a more precise feel for it, and its putative interior.

![]()

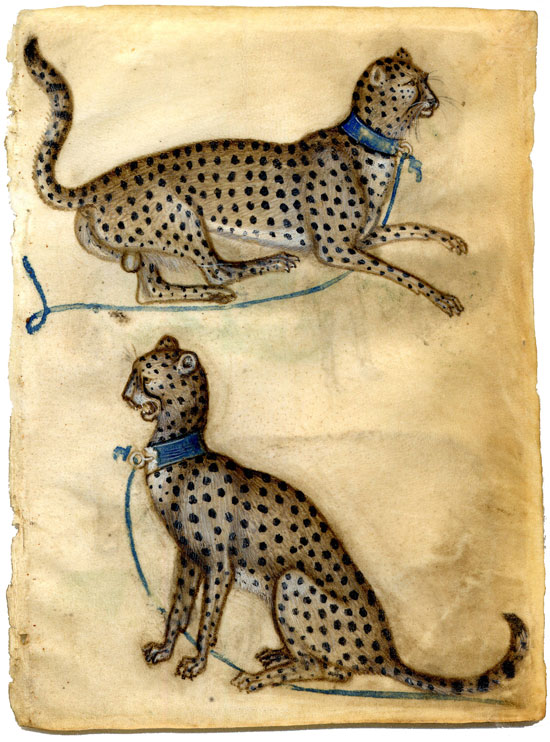

Humans, like a leopard or possible cheetah I once saw at London Zoo, are wont to walk relentlessly around and around the objects of their devotion, or attention, or delusion.

—devotion, attention, delusion—

– Study of Cheetahs

Giovannino de'Grasso

In walking around—circumambulating—we mimic a cosmic rotation. To circumambulate with your right hand to the centre is a solar charm. Thus we circumambulate to blot out sins, to draw down propitious consequences; or to search out the dark side of our moons.

The Greeks, in a ceremony known as amphidromia, processed a new-born child at a brisk pace around the family hearth. Clockwise. According to Grimm1 in Estonia, the father was obliged to run around the church during baptism. The Hindu bride walks three times around the hearth. Similar customs pertain in Rome, in ancient Japan, in orthodox Greek churches. Plutarch narrates that the Gaul Vercingetorix, before surrendering to Caesar, walked three times round the chair on which Caesar was sitting. Always clockwise.And we, buried deep in some greater future’s mythical past, deep in Ur-Norbiton: we go widdershins, grinding our gears against the cosmic rotation.

I do not recall my leopard’s choice of direction, but in my head I picture it as counter-clockwise, the creature gently, insistently unwinding the skein of her animal soul.

—widdershins—

– West Wall, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Chapel, detail

Benozzo Gozzoli

![]()

The station is the Great Gate of Norbiton. It stands like a quest barrier on the northern rim of the ward.

—quest barrier—

Its main entrance is on the Coombe Road looking away from Norbiton; there is an exit also on Norbiton Avenue, leading into the fabled city. Its two platforms, running trains into Wimbledon and Waterloo and out to Kingston and beyond (the trains in fact loop back around the park and return to Waterloo by other routes) are connected by a subway. The borders of Norbiton proper follow the railway line: duck under by the subway and you’re in. Platform 1 is in Canbury; platform 2 is in Norbiton.

—you're in—

On platform 1 there is a modest coffee shed, run by Neville. Neville is fortyish, stout, frets over plastic cups and small change, makes a really very acceptable latté. The inside of the hut is decorated with paintings in which we recognise the hand of his children, vague infantile studies in medieval perspective, where daddy’s head is very big and the rest of the stuff of the world is jinked in anyhow wherever it will fit.

Clarke has a cappuccino sweetened with four little bags of artificial sweetener; Hunter Sidney has a cup of tea; I have a latté; Emmet Lloyd has what we’re having; and Kelley has nothing.

Kelley has his dogs with him: a pair of aristocratic loping greyhounds who pay no attention to any of us for the duration of the walk barring the occasional cock of an ear when Kelley speaks to them; they seem set on a mission of their own, moving through the space of their own contiguous city.

I am growing restless because Neville’s platform is more Canbury than Norbiton, so we drink up our frothy milk, thank Neville, and pass out on to the Coombe Road.

The circumambulation is under way.

![]()

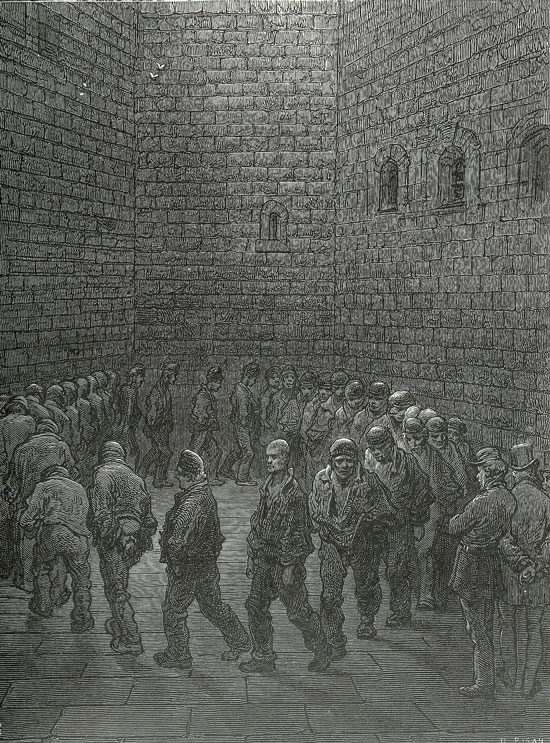

Farmers build city walls to keep nomads out. Nomads stop at the city walls.

Thus Gilgamesh built the walls of Uruk, enclosing its sheepfold and date field and temple and the city itself2.

But we forget. What are farmers, if not nomads caught in some inexorable economic eddy? In fighting Enkidu the wild man, Gilgamesh was wrestling himself and we, city dwellers of Norbiton, are barely polished wild men in exile. We have made our polis, our civitas, far from our homes, attracted by some aggregatation of matter and energy—call it a city—much as comets are jogged hurtling from the Oort cloud by the chance passage of stray stars.

Thereafter, failed nomads, we exercise our trapped souls like prisoners, or leopards, or orbiting comets: eliptically, in grim circles.

—grim circles—

– Prisoners Exercising in Newgate Prison Yard

Gustave Doré

![]()

Leaving the station on the Coombe Hill side, we work our way up to the northern boundary along Station Road and then Gordon Road.

Gordon Road skirts the railway line and overlooks the back of the telephone exchange on Birkenhead Avenue. Just past the Big Yellow Storage Unit, and before rounding the dogleg at Wickes the builders’ merchant, a concealed path (Orchard Way) leads under the railway arch past Orchard Cottages and out of Norbiton.

—out of Norbiton—

The path runs directly to the door of the Norbiton and Dragon3, coiled, as it were, in the doorway to Norbiton.

—prospect of a pint—

We hesitate over the prospect of a pint, then double back to Gordon Road, and briefly join the A307 circulatory system as far as London Road, passing, on the way, one of the entrances to Tiffin School. We join the London road at the Lovekyn Chapel.

The Lovekyn Chapel is, I suppose, the oldest building in Norbiton. My brother used to teach the piano one day a week at Kingston Grammar School (which lies, for the most part, beyond the ward) and the Lovekyn Chapel was his practice room.

—practice room—

The chapel stands for the most part unregarded at the junction of two busy roads, and while it would be pleasant to reflect upon the 15th century chapel as an oasis of music and sanity isolated in a turbid river of madness, it is worth recalling that piano lessons, for both teacher and pupil and anyone who happens to overhear, are in themselves a chaos of half-scales, repeated dinning fragments, gear-grinding incompetence and the occasional moment of confusing beauty. My brother, shuttered in a pullulating asylum of proto-music, might have found some relief stepping into the open space of the light-controlled junction, joining the graceful flow of automobiles and pedestrians, participating in the clear patterns of daily life.

We cross the London Road in search of the narrow passage way leading between, on one side Kingston Grammar School (which Edward Gibbon briefly attended), and the gardens of the houses of Minerva Street on the other, towards the Fairfield Recreation Grounds. The Grounds lie outside Norbiton. They have perhaps four measured and whited football pitches, which are silent, it being Wednesday morning.

—silent—

Clarke finds a half-soft ball in the bushes by the fence, and blunders out on to the Rec., thumping the ball in front of him; in a minute or two Clarke and Kelley and Lloyd are having a bit of a kick around, Lloyd in one of the gaping goals and Clarke and Kelley vying for mastery of the ball; neither is much good, although Kelley might have been once; Clarke is long-limbed and ungainly, physically ponderous but an encumbrance for Kelley who contents himself with appearing not to care too much. Clarke does a lot of swearing, and a lot of standing with his hands on his knees, but in the end interposes his bulk sufficiently well to have more of the ball.

Hunter Sidney and I watch over the railings. I ask him why he supposes Kelley has come along. Hunter Sidney never says very much—it is too painful for him, I suppose—but he says now that Kelley likes to get out of the house, does not like to go into work, so here he is; he has a queer history of some sort—Clarke thinks he is a warlord, a gun-runner and IRA warlord, that he has in the past blown men to perdition; so he might be looking for solace in fretful inaction. But Clarke has a taste for drama, revolution. More and more as your life nears completion, Sidney notes, you hesitate in the mid-spaces between action and action; you sit and wait in the garden of your soul. It need not be anything more than that.

Clarke works some sort of clutsy but effective move on Kelley and toe-punts the ball past an incompetent Lloyd—who I realise now did not once touch the ball—and we are off again, circling the city, raising it from the dust.

![]()

I am not ruling out the possibility that some journeys might be linear, but processions are cyclical, whether in space (walking the boundary of a parish, for instance), or in time (anchored to the Church calendar or the wheel of the seasons).

In 1459, Benozzo Gozzoli executed a series of frescos around the walls of the private chapel in the Palazzo Medici, depicting the procession of the Magi to Bethlehem. The grandees of Florence—Cosimo de’Medici, his son Piero and his grandsons Lorenzo and Giuliano, and illustrious guests (Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Sigismundo Malatesta)—are depicted making their circuit from the east to the west, a clockwise procession to one whose head is bowed in devotion, if not to one whose head is raised in praise, or who watches from the sulphuric pits.

The procession traverses a stylised landscape, peopled with camels and dromedaries, leopards and hawks, pheasants and swallow and quail; with its high horizon, this is not a landscape at all but a Franco-Flemish tapestry; the trees are manicured, the champaign illustrative, as though these lands were brought to ordered life by the procession which circles within it, in its rites and devotions.

—rites and devotions—

– Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Chapel, East Wall

Benozzo Gozzoli

![]()

Gozzoli’s chapel décor is commemorative: it was frescoed in the same year that Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Sigismondo Malatesta and others came to Florence to attend a summit with Pius II4, who was intent on crusade. Florence showed its absurd power with jousts and ceremonials, banquets and dances, and hunts involving lion and giraffe, all choreographed by Cosimo’s son Piero, who was also responsible some months later for directing the work of Gozzoli on the chapel frescos.

The chapel was a centre not only of religious devotion in the Palazzo Medici5, by now the de facto hub of Florentine power, but also of political theatre. It was in the chapel that visitors to the Palazzo were greeted: Galeazzo Sforza, for example, who stayed with his entourage in the Palazzo Medici during the 1459 festivities, and who, aged 15, must have wondered at this small, densely configured chapel, like a packed grenade, and its contrast with his father's own vast and crenellated castle.

Sforza would later be assassinated, in a plot perhaps connected with an attempt on Lorenzo de’ Medici’s life; Italian politics was a great field of disarray, brought here and there, in fits and starts, into still and ponderous order: in the chapel, for instance, where the circling dumb show, the circumambulating grandees and princes and condottiere circled, not a religious object, but an ill-defined locus of something black, something malevolent; whirling themselves in the process into a scintillation of brocade and gold leaf6, an iridescence of power. Gilgamesh built the walls of Uruk, after all, only to terrorise its sons and daughters thereafter.

But all that black power has its blind spots, its points of resistance. Thus our artist has slipped in two self portraits, one on the West, one on the East wall. He flickers through the procession in his own mobile performance, his own magic, his circumambulatory conjuration. He wears different hats in defiant whimsy. Catch me if you can, as I have caught you.

—whimsy—

– Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Chapel, details

Benozzo Gozzoli

![]()

From the junction with Fairfield South, we head down Villiers Road, which marks the western boundary of Norbiton and, at the point where it meets the Hogsmill River, its most extreme south-western tip.

—extreme tip—

The Hogsmill River is where Millais drowned his Ophelia. Villiers Road crosses it these days over a flat bridge. On the near side, a path leads alongside the river for a hundred yards before a fence halts further progress. We are left with the alternatives of either wading down the river or scouting out to the south of our domain.

—wading down the river—

The river itself is flat, placid, ankle deep. There are plastic bags caught in the weeds and bobbing plastic bottles, and the buzzing of river insects. Its banks are probably well known to children and teenagers, who are accustomed to getting down low to see the terrain, getting into the crawlspace of the world. But this is a little more than we bargained for and we continue, without discussion, down Villiers Road to Lower Marsh Lane, up the far side of the Hogsmill valley towards Surbiton.

Lower Marsh Lane has the feel of the country about it, or at least the feel of those fractal edges of London in its more ungoverned, less compacted use of space. Civ Clarke says that in Rome on an outlying road like this you’d find grubby boys herding goats or piling up washing machines on the hot scrubland by their gypsy encampments. But this is not scrubland; it was no doubt once marshy, the sludgy beds of the Hogsmill spreading itself out in choked oxbows and stagnant meanders. Now it is the sewage works, and the walker is surrounded by invisible wisps of light high gases. The security guards who patrol, we are informed, twenty-four hours a day behind the wire fences might from time to time be led astray in the small hours by the wills-o’-the-wisp, the sewage sprites, dancing over the rich soaked land, the big squelch of river valley and sewage seeping across the land. Perhaps they are sucked down, smiling delirious oracle smiles, to roam the silent dark lost forests for eternity.

—sewage sprites—

We will have to come back here by night. By day, a weekday morning, there are a few people going about their business. The Surbiton side of the lane is lined by tatterdemalion stone cutters and sellers of granites and marbles for monuments—some of them, as I learn later, part of Kelley’s spidery business (Kelley says nothing about it as we pass them); they are spread out along the road with strips of stone leaning this way and that, old men with leather hands whitened by the stone dust stooping about among their inventory; and then the cemetery, Surbiton cemetery, which, as we peer over the brambly railings, seems only half full, as though the Last Trumpet were still many drowsy centuries off; the corpses have hung up signs, gone off somewhere. A notice on the gate says that someone is carrying out an audit of the gravestones and monuments for safety but nothing much seems to be happening. Perhaps the notice has been there for years, the progenitor of this audit now lying in some other graveyard and the dead here, after a momentary hiatus of activity, left to themselves again, a hidden corner of municipal informality, a pleasant enough place to spend eternity, or some of it at any rate.

—some of it—

After the cemetery Lower Marsh Lane thins to a path, still straggling between the sewage works and some old pumping stations with their abandoned winching tackle and wonky Thames Water signs. We pass Berrylands station, whose steepling platforms are ranged against Norbiton station as one castle might defy another across a rich champaign, re-bridge the Hogsmill and cross back into Norbiton along the Kingston Road at the junction with California Road.

—steepling platforms—

Berrylands Station

![]()

"DEAREST H... I’ve been so overwhelmed with work, and the mountain of the Unread has piled up so, that only in these days here have I really been able to settle down to your "American Scene," which in its peculiar way seems to me supremely great. You know how opposed your whole "third manner" of execution is to the literary ideals which animate my crude and Orson-like breast, mine being to say a thing in one sentence as straight and explicit as it can be made, and then to drop it forever; yours being to avoid naming it straight, but by dint of breathing and sighing all round and round it, to arouse in the reader who may have had a similar perception already (Heaven help him if he hasn’t!) the illusion of a solid object, made (like the "ghost" at the Polytechnic) wholly out of impalpable materials, air, and the prismatic interferences of light, ingeniously focused by mirrors upon empty space."

William James, letter to his brother, Henry James, Salisbury, Connecticut, May 4, 1907

![]()

What William James is saying is clear, even if he playfully skirts around it by saying the opposite: it is the walking around an object that conjures that object. There was no prior object. There is no object. There is only the walking about.

Thus we think about, or speak about, or god help us write about. We write spells hoping to conjure objects which do not otherwise exist—as objects, that is. They must presumably exist on some continuous plane of experience, or energy, or matter. But we cut the cloth of the world as we move through it. About it. Thus gods emerge in the desert air, in the rock of the mountains, as we move our sheep to pasture. Gods emerge in the city when we build great empty temple, sculpt processions around their exteriors, their curtain walls. Effigies of movement. (Gods emerge in movement. To sit, to stay sitting, is to suffocate your god).

But why this particular path? Does it not suggest an object? Dimly, perhaps.There is something named in there, something vague—a Norbiton. Generations have walked about it, and named it, and considered it. It has grown from some nodule, some clumpiness, some irregularity in the fabric of the landscape—in the case of Norbiton, an outlying farmstead, perhaps. Something has started generational feet moving, generational minds passing over hidden topologies. There is something there, something in what we walk or talk about, that we desire. And desire, like the gods of the desert, is at once vengeful, hot, mobile, inexplicable.

![]()

Back on the Kingston Road, a disagreement flares up. Clarke can’t be bothered to continue. If anyone is going to suffocate a god by sitting still, it is Clarke.

We stand in the street and look around, discussing possibilities. If we want to complete the circumambulation we’ll have to turn up Dickerage Lane, cross the railway and wind back towards the station along Orme Road and Gloucester Road; but this would take us outside Norbiton again, we would complete our circuit in the manner of a besieging general looking for weaknesses. Or we could keep inside the railway line, following Douglas Road and Porchester Road and Homersham Road as far as Norbiton Avenue; but we wanted to throw a girdle around the earth, not shave off round Norbiton's imagined corners. This is Clarke’s line of argument—there will be no point completing it unless we walk along the railway line.

While I disagree, I’m not going to put up a fight, but Hunter Sidney says we should do things properly. We need to make a good start. We've come here for a reason and we should see it through.

Clarke counters that for a project or series of projects dedicated to the failed life, cocking up a foundational venture would be not only appropriate but proleptic. Hunter Sidney tries to remind him that the failed life is not about failure, but it is a difficult argument to make and he is running short of breath.

Kelley, who has not, seemingly, been paying much attention but has stood a couple of yards off smoking a cigarette, now says

"Doing things properly is right; but part of doing things properly is knowing when to ditch them, or which bits of them to ditch. This fucking walk, for a start.”

He has a point. Building is as much about dereliction as construction. Letting the form of the project emerge. I am suddenly convinced that what the project needs is a meta-circumambulation. A futile abortion of a foundation ritual. We should head up to the allotments and have a drink.

Hunter Sidney gives up the fight and we walk up Kingston Road. As we go, we discuss the building of cities. Or rather, Kelley gives us a lecture on the building of cities. He says this is no way to build a city, this voodoo traipsing in circles, this mordant musing over dead stones. (And he is right: we have learnt nothing, established nothing, defined nothing). Nor, contrary to what he implied earlier, do you build cities by dereliction. No. You build them one brick at a time, and someone, somewhere, has to feel the heft of every single last solitary brick.

He explains that when he built his football stand (the Palladian North End—see Architectural for a refresher) in the 1980s, there were weeks and months with no work going on at all. And he would go over every day and just pick stuff up and shuffle it around, thinking he would be smoothing the way for when they got back to it, how the bricks should be there and the trucks could pull in here and so on. And then he took to laying courses of bricks himself.

When you are putting together something of that size, he says, and you are reduced to doing it a brick at a time, by yourself, in your off-hours, and every time you raise your eyes to wipe the sweat away you see only how much there is left to do, stretching off to the horizon, piles of bricks and stacked bags of cement and who knows what else, rusted scaffolding and heaps of rubble and hardcore, like some vast jigsaw and you cannot even remember what the picture was of. Well, he says, my whole memory of that time is of me labouring in futility in the rain, trying not to think about how it was impossible to do all this on my own. I don’t know about your Ideal Cities, but that’s how real ones are built right enough—one bitter fucking brick at a time.

![]()

Cities rise and cities fall. In tracing their boundaries, fault lines in the landscape, we raise them up or bring them down; there is a magic to it.

When Israel, returning out of Egypt, set about conquering the land of Canaan which it had been promised, but not gifted, its first obstacle was the city of Jericho. Jericho, Ur-City. Joshua marshalled his men to walk once around the city each day, processing the Arc of the Covenant, for seven days, and on the seventh day, to walk seven times around the walls, and blow their trumpets. And the walls fell.

It is not clear if Joshua marched his army widdershins in some drawing up of black chthonic magic; or if what he was doing in destroying Jericho and its inhabitants was a constructive, godly, therefore cosmically congruent, i.e. clockwise-leaning act.

It does not matter. It did not happen. But the story—not a story, really, so much as a formal memory of a pastoralist people's sheep-eyed, goat-eyed mad encounter with the first city—understands something. As a small boy at a convent school I was invited, with my little classmates, all unknowing, to process the boundaries of our parish church in some Marian rite. There was incense, a cross, mad devotions, and a crocodile of infants, my round and ignorant face among them. All the magic that could be summoned by the crowd was summoned. And then? The priest is likely dead, many of the nuns and teachers. Some of the children too. The rest of us are grown old and forgetful. There are no longer any traces of our collective madness on that suburban pavement.

But I remember, because it was different day. We were not in school. We were out in the streets, in the sunshine, enjoying what for a six-year-old is a version of freedom. Walls, perhaps, were being undermined. And who knows? Perhaps elsewhere, down some long and resonant future, on another day of freedom, shimmering sympathetic cities were steadily rising out of the dust of the plains.

—out of the dust of the plains—