Contractual

—precisely located—

– Statue of Gattamelata, Padova

Donatello

We are each of us dispersed over a map of contract. The more contracts you are party to, the more precisely you are located on that map.

The map of contract is four-dimensional: most contracts are of fixed duration and extend over time as much as they interrelate individuals and corporate bodies through space. And to the extent that contract space—the totality of all possible contracts—is personal to, and derived from, each individual, perhaps map is the wrong word; perhaps it would be better to say that we each occupy or traverse on a daily basis a sphere of possession defined or opened up by our ongoing contractual relations.

In theory—call it a legal fiction—each time you sit down and uncap your pen and make a show of reading over the terms, and then put your name to a contract, or make any kind of promise in a public or domestic or personal sphere, you do so from somewhere: you emerge from an uncontracted space, stepping out naked and startled, as it were, from the primitive forests of your soul. The contract marks your entry into civility.

This space is very often convergent with an actual spot on the face of the earth—your desk, for example, or the sofa in your living room; if you are Federico da Montefeltro, great condottiere of the quattrocento, you emerge from a nest of rooms around your studiolo, directly into the halls of public business; if you are a Polyphemus you emerge, blinded, perhaps bewildered, perhaps chastened, from your fortress of caves, your schizoid private space, and you grope your way towards civility.

—grope towards civility—

– Federico da Montefeltro — Piero della Francesca

![]()

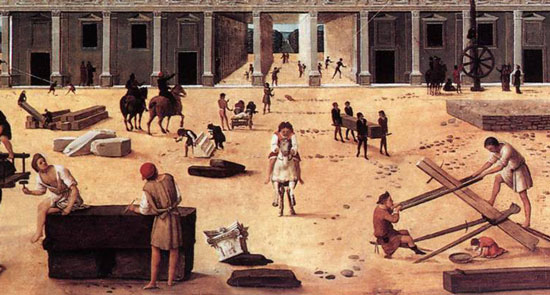

In quattrocento Florence the standardised, notarised contract is a tool that is a surprisingly little-used tool.

Agreements, for example, between merchants wanting palaces built and the wallers and architects who would build them were loose and flexible; a fee would be agreed, perhaps the nature of the materials to be used (often supplied in any case by the patron); the waller would not usually have the personal liquidity to pay for all the workers he in turn sub-contracted (again, without standardised legal instruments), so would draw on the patron from time to time as though on a source of credit.

—loose and flexible—

– Building of a Palace — Piero di Cosimo

Disagreements would be settled usually by the responsible guild, who had an interest not only in protecting their members but also the good name of their trade. It was not a perfect system—the lack of formal constraints would more likely work against the small tradesman or artisan than against the wealthy patron—but it was a system appropriate to the scale of the city and the structure of its corporate governance.

We can conclude therefore, that when a contract is drawn up and signed and notarised, it is a sign that some new dimension has entered the agreement. It has nothing to do with public, private, domestic spheres. The axis along which it operates is external – internal. A contract is a sign of externality.

By the end of the century contracts are becoming more common. They stipulate terms and conditions more fully, they include non-compliance clauses, penalty clauses. Externality enters internal social relations, the contract becomes a document of mutual coercion. Your townsman, in matters of business, becomes, as a legal entity, a stranger to you.

This is why you, now, have a contract of employment, a rent agreement; why you signed contracts on your mobile phone, your internet connection, your financial instruments. This is why you are married.

—why you are married—

– Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine — Hans Memling

You are surrounded by strangers. The contracts you accumulate, so far from being a measure of conviviality, are a guarantee of your privacy, of your social autonomy, of your sundered social being—of your externality—depending on how you look at it.

But you won’t really know this, you won’t puncture the little vacuole of violence at their heart, until you breech some of their terms.

![]()

I am moved to consider the contractual basis of my public life because I am driving with Hunter Sidney to Richmond to negotiate a contract of employment, more or less, with that squat-bodied, crook-nosed, bandy-legged old condottiere, Tony dell’Aquila, Duke of Kingston.

I opened the door to the Ideal City by tearing up my contract of employment, and the more nebulous contracts of social engagement that it entailed. As Citizens of Norbiton: Ideal City we have endeavoured to create, not necessarily friendships, but a similarly hydraulic system of contracts, of mutual cooperation, around our various projects.

But now that I am leaving, for the first time, the city which I have come to inhabit, I am considering how to manage my relation with dell’Aquila. Richmond is an alien city, after all. And Tony dell’Aquila is a stranger.

![]()

I have never met dell’Aquila but as we drive over I am telling Hunter Sidney that in the precarious, perhaps hypervigilant mental state in which I find myself at this juncture, I have started to identify Tony dell’Aquila with Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, and Kelley with Sigismondo Malatesta, Lord of Rimini. Renaissance princes, gangsters, humanist patrons, vulgar rich: call it a sort of mental shorthand.

—mental shorthand—

– Sigismondo Malatesta — Piero della Francesca

Federico da Montefeltro made his fortune contracting his military prowess, or at any rate reputation, out to the highest bidder. The condotta, the contract of a mercenary, provided a guarantee and a commercial structure to military operations on the Italian peninsula in the quattrocento; the various kingdoms and city states hoped not so much to defeat their enemies on the field of battle as to outbid them, to out-negotiate them.

Federico’s native lands around Urbino were poor then as they are, relatively, now; agricultural production was limited by the marshy and mountainous terrain; industrial production was virtually nil. But the Duke could lead his little armies out for a few weeks every year, to the terror of Milan, Florence, Venice, and lead them back in again without necessarily donning his armour. No one doubted his martial virtue—it was, after all, stipulated.

After the Peace of Lodi (1454) his condotta with Milan paid 60,000 ducats per year in peace time and 80,000 ducats in time of war. Barring some brushes with Sigismondo Malatesta, Lord of Rimini, and the brutal subjugation of Volterra, in revolt from Florence, and perhaps one or two other small jobs, it was mostly peace time and he was able to concentrate on building the palace and the court for which he is now, occasionally, remembered.

When we arrive at Richmond, Hunter Sidney stays in the van and I walk through to the garden to find Tony.

![]()

Castiglione, writing a generation or two after the death of Federico, called the Palazzo Ducale a city in the form of a palace. But if that is true it is a city of interiors.

—city in the form of a palace—

From the outside, the palace is a prickly object. As you drive up the winding road to the town (I have always come to it by bus from Pesaro) you see the twin towers, the strip of loggias; you see an interminable jumble of brown stone and little windows and tiled roofs, a fractured mass of confusing projection and whimsy. It is picturesque, but it makes no obvious sense. Walk up and around the back (or is it the front?) and as you approach the entrance from the east the old medieval facade is perhaps even less prepossessing – prison walls, a fortress, a blank toad squatting on this little town.

—blank toad—

Around the entrance, however, you get the first indication of the nature of the articulation of space within, as if the interiors have seeped out of the doorway like classical magma: there is a spattering of rustication, a leisurely asymmetry in the courses of windows, marble moulding around the doors and window frames.

—leisurely asymmetry—

– Photo: yannick_anne (Flickr) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

This is a Renaissance villa that has been excavated from a medieval fortress. Three generations of architects1 worked with Federico da Montefeltro to bring the unsystematic accretion of centuries under formal control. They did this partly by restructuring the existing palace and partly by extending to the North and West, the site of the Duke's and Duchess's private rooms and the hanging garden.

It is a building that looks out over the landscape from within, not in fearful anticipation but in the security of possession. The interiors are rational in the same way the mind itself is rational—coiled, looped, intestinal, surprising, gravitationally centred, intermittently solar and shaded; Giuseppe Marchini writing at the end of the nineteenth century called them (the rooms of the palace, not the chambers of the mind) an “abstract ideality permeated with light”. And so the functional and ambulatory logic of ceremonial, executive, domestic and private spaces came to be expressed in a series of nested and interconnected centres. A(n ideal) city in form of a palace.

From another (counter-whimsical) perspective you might suppose that the palace was not quarried from the brooding medieval clay but grown from the logic of its ornamentation. As though in some Dionysiac moment of transformation the tendrils and arabesques and stamped iterative motifs of each doorway and window frame and fireplace and corbel had spread over the whole fabric of the old Saturnine medieval rocca, pushing at its cracks and weakness from within, rearranging, carving out, sorting and pushing stone from stone from space, like some grotto of imagined rationality; and then retreated like a tide, their briny scouring and gouging work done.

—logic of its ornamentation—

– Iole Doorway

Thus on one plane there is at Urbino a Renaissance spatial organisation hidden within a Medieval fortress. Read this way, the Duke is a beneficent minotaur at the heart of a complex functional space (overlapping and perhaps mutually informing domestic, devotional, ceremonial spheres of possession). In the mould, then, if not the precise form, of all Court bureaucracy.

However, on another plane, as you stare harder, the single point of the Duke resolves into a cluster of independent sub-systems or objects: his wedding contract; his routine of study; his presence as executive and judicial centre of his realm in the off-square Camera del Bisquadro; his diplomatic double persona (the commercial and military condotta blurring over time with the Knight of the Garter and Papal defender); his daily passage through his inner realm, intarsia of the studiolo, polychrome marble of the chapel, white and gold of the public rooms; his contracted building arrangements with the Laurana and Martini and their dust-trailing workmen who co-inhabited this termite space for thirty years.

The palace, taken this way, is not the natural outgrowth of a single unified being, a unitary consciousness or Will imposing itself on the material conditions of its existence. It is, rather, a precarious complexity, rational precisely insofar as it is precarious.

And by precarious I mean something quite precise. I mean that, whatever it is we are talking about—Federico as cluster of objects, palace in form of a city, mind grown inward in the accreted coral of ornamentation—it is both set up, held in place, and renewed by the discrete contractual obligations not only owed by others, but to others.

![]()

Hunter Sidney, to whom I outline much of this in the van on the way over to Richmond, later on counter-relates the following:

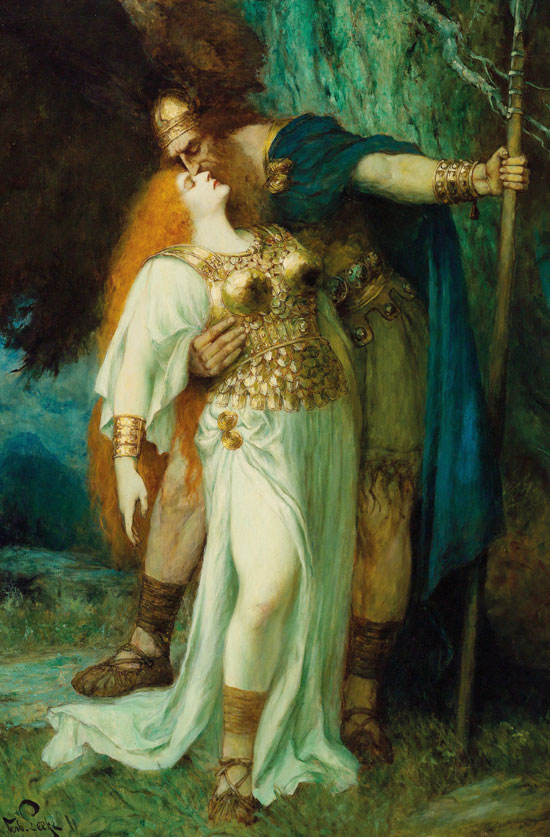

Wotan, Wagner's wandering god, has the terms of the contracts that guarantee his power etched along the shaft of his spear. He is an Old Testament god, and an Olympian god, stated in other terms.

His spearshaft was made from wood torn from the Welt-Esche, the primeval Ash; he wrenched the wood from the tree as a young and impetuous god. The tree withered and died but the spear is as sound as ever. In similar vein he sacrificed an eye so that he could take Fricka for his wife. Now, impotent Cyclopic god, he wanders the face of the earth trying to find a non-punitive non-compliance clause—a way of extricating himself from his contradictory contractual obligations, including that with his wife (goddess, not incidentally, of properly contracted marriage).

—extricating himself—

– Wotan's Farewell to Brünnhilde, Ferdinand Leeke

Only his grandson, Siegfried, conceived in an incestuous and adulterous liaison, grown up in the wild forest under the tutelage of an amoral dwarf, knowing nothing of fear, understanding nothing of the world, has sufficient anti-authority to destroy the great god’s power, shatter his spear, immolate his daughter.

All this Hunter Sidney tells me when we are sitting back in his upper room. The lees of our tea are cold, and it is dark outside. We are all, says Hunter Sidney, wandering Wotans. We all come to that in the end, playing out the inevitable consequences of a network of obligations thrown together at random, on the hoof, in the impetuosity of youth. It was Federico’s privilege to do so in marble. It was Wotan’s curse to do so on the World's stage (or Bayreuth, as it is known). And it is our own muddle-headed defiant fate to do so in Norbiton.

![]()

Hunter Sidney's is a gloomy soul at times; I am not so sure that we are entirely trapped by our youthful undertakings. But equally I am not sure if the relationships or contracts we form in our youth are of less weight than we suppose at the time, or more. Or both: less in material terms, but more in terms of psychic hauntings.

But then Hunter Sidney has been married and I have not. He maintains that in marriage you either surrender your autonomy or swallow that of a fellow individual, or you attempt to build a new corporate entity.

And that last may be an impossibility. Marriage, historically, is about appropriation, or stipulated exchange of goods (procreation, dynastic alliance, social or financial advancement) the precise balance of which may vary according to place, time, and social degree. The notion that in marrying we are forming a romantic cooperative conceals a more brittle, much edgier truth.

In Florence in the quattocento the betrothal and marriage of a socially well-positioned couple was attended by a series of private and public ceremonies.

The betrothal took place in a private space—the bride's father's house, typically—and involved the witnessed signing of a notarised contract, which stipulated, among other things, the size of the dowry, the nature of the trousseau and the groom’s bridal provisions (typically a bed, a pair of wedding chests or forzieri, a lettuccio (a sort of divan) and so on). The betrothal was either accompanied or followed after some days by a ring ceremony, also conducted in the bride’s father’s house; the ring ceremony entailed a banquet and a church blessing, and the marriage was frequently consummated, once again, under the bride's father's roof.

The bride would then remain in her father’s house2 until the groom came to carry her in procession back to his own house, on foot, as required by law if both houses were in Florence.

This procession was known as the vincolo vero, the real bond or chain, and was the first proper public display or acknowledgement of the alliance.

—vincolo vero—

– Rape of the Sabine Women, Sodoma

It was frequently attended by riotous behaviour, both good and ill-natured, on the part of rival families, of the two families themselves, or of the popolo minuto, which would avail itself of the opportunity to get drunk, mock its betters, vent its spleen.

The union of two Florentine families of the ottimati, in such a clannish city, was a brutal act, as though in forging this contract all order and sense were violated, the celestial dome had cracked and was venting spiritus, effluvia. Marco Antonio Altieri, writing at the beginning of the cinquecento, likens all weddings to the rape of the Sabine women. The groom’s party, coming to collect the bride, were as a brigata (Altieri's term) descending on her house; in some circumstances there were tableaux acted out of forced entry and submission.

The only thing that holds these vast social forces in place, staples together the cracked dome of the spheres, is the notarised contract.

![]()

"Si che representandose in ogne apto nuptiale la memoria del quel rapto de Sabine."

Marco Antonio Altieri, Li Nuptiali, Enrico Narducci, ed. (Rome, 1873), 73

![]()

Another interpretation of the vincolo vero and the ceremonial attending the wedding would be that the bride continues to dwell in her father’s house, that the marriage is consummated under his roof, because she, with her father’s connivance, is establishing her place—the place from which she emerges. I do not know if this is historically or psychologically likely, but it appeals to me at some level. When I quit my job and spent the ensuing months watching Star Trek, thinking nothing I did not want to think, allowing my disembodied spirit to float at large around its objects of knowledge, I see now that I was establishing a fortified camp—a place (in my case) not in which I expected attack, but from which I planned to sally forth.

Compressed into one room, like a singularity at the heart of (my personal) Norbiton, was all that matter of the Duke’s palace at Urbino. This was the place that would be always at my back; all contracts, promises, agreements would start here; I would calibrate my contracts, from this place.

It is important for me to know this. Until now all my contracts have been within Norbiton. But now I am leaving the City and its mutually-assured freedoms, and am striking out into the crooked world.

![]()

The contractual agreement I reached with Tony was, on the face of it, appealingly loose. He wanted me, not to labour on his garden, but to help him plan around some changes he was making to it. On the basis that I would first give it some thought, then make some recommendations, then revise my recommendation, plan the work, and oversee it, there were many points where my involvement could lapse, or my fees escalate. The money he was offering for the first stage – having a think and making some recommendations—was generous considering I had no experience or expertise, nor any other calls on my time.

I say on the face of it, because the misgivings I had experienced on leaving Norbiton had resurfaced in his garden. I was obligated now to think about garden design, to read a little around the subject, the history of Italianate Gardens. That was OK. I had some money up front and plenty of opportunity to call a halt. But, sitting in the Albert and having a pint with Hunter Sidney and Clarke, I began to suspect that the soft nature of the contract concealed operations at levels of which I was unaware. I had come to dell’Aquila on the recommendation of Kelley’s wife, presumably with the acquiescence of Kelley; but Kelley and dell’Aquila had a history. Kelley’s wife didn’t go out, but had maintained contact with an enemy of her husband. Was I just gardening, or was I some sort of intermediary, a retainer of Kelley’s sent as a conduit of diplomacy, perhaps, or espionage to a rival court?

Or was I—a deeper or possible more pragmatic fear—merely a clause or a term in someone else’s contract?

![]()

Contracts vary in their detail. Many contracts, for instance, contain pages and pages of unread standard clauses that may or may not be invoked, depending on circumstances. Clauses can be gestural, rather than effective. Or ambiguous, poorly worded, mutually misunderstood.

You might argue in consequence that the number, and validity, and extent of the contracts you have made with other individuals and corporate entities could give you, if you knew how to triangulate the values, a measure of your social being, and a measure of your freedom, properly understood.

A measure, too, of your aspiration to freedom. A contract is a promise, and it is in the capacity to promise and to forgive that Hannah Arendt locates our power to act in concert – to take Action. To act in concert, moreover, in pursuit of a common goal of limited scope. A project, say. A garden, a library, a city in form of a Norbiton.

The texts of our freedom, then, lie all around us ready to hand; but, as I discovered in dell’Aquila’s garden, not only are we largely ignorant of their hieroglyphic intent, not only do we find it hard to gauge the relative weight of the clauses; but at the point where we think we might have got to the bottom of it, to have resolved the ambiguities into some workable understanding, we look up, take off our spectacles, rub our eyes, and see Federico da Montefeltro, or Sir John Hawkwood, or the Gattamelata, thundering over the horizon towards the gates of our city, looking to close out a contract of their own, made with unknown third parties.