Diurnal

—who sees the sun rise?—

– Christ in Gethsemene

Andrea Mantegna

Who sees the sun rise in Norbiton? The sunrise is a concealed and to all rational purposes a fictitious virtue; it happens elsewhere, off across the city, probably to someone else; and not every day. It is a promise of poetry which has already evaporated in the moment of fluorescence. A promise never fulfilled.

There is no sunrise then in Norbiton, but there is a dawn. The dawn is a universal beneficence. It touches even us. The dawn, if you care to notice it, is always up there somewhere. It happens regardless. It is a routine of life. And because it is a routine, it works.

![]()

The transformational power of the sun was well known to the renaissance magus, for whom solar or Jovian energies and influences countervailed against the melancholy opacity of Saturn.

Perhaps you do not need to be a renaissance magus to understand that.

The transformational power of the dawn, however, is not merely associated with the revivifying power of the sun. It is associated, in Norbiton and perhaps elsewhere, with the reassertion of meaningful routine following a long night of formlessness.

Hunter Sidney, insomniac, says that in the dark months following the end of his affair with the woman for whom he had left his wife and family, the only consistent mental calm he experienced was in the first vertical hour of his day. The dawn has a way of straightening your thinking. By night you have no structure of habitual action to fall back on; you just lie there. But with the dawn you can, for a brief period, test the power of some simple matutinal routines, before those routines became skewed or swamped by a mass of increasingly desperate habit.

Whatever the details of Hunter Sidney’s personal Gethsemane, I think we can deduce from this a first working distinction between habit and routine. Habit is a dead accumulation; routine has an outcome. Habit is an inverse index of the intensity of life, routine is a productive process. Habit is contingent; routine is necessary. Which is another way of saying, routines mean something; habits do not.

Although let us be clear: routines are composed of sub-routines, which are in turn composed of habits.

![]()

There is no velleity in habit—a habit is either good or bad, virtuous or vicious.

But while there is no velleity, there is ambiguity: you will as occasion demands see a habit as either deleterious or beneficial to your productivity or general well-being, depending, if I am correct, on whether or not it maps to a routine.

Mrs Isobel Easter, for instance, whose agoraphobic life is a scaffold of habit, claims that a record of her approbation or disapprobation would read like a history of tides.

—agoraphobic—

– Scaffolding in a side-chapel of the Basilica di Sant'Andrea, Mantova

She lists some of her habits for me.

• The habit of abandoning books three quarters through, and dog-earing the pages Fruitful impatience or fecklessness? Personalising the text or indifferently urinating against it?

• The habit of sleep in the early afternoon Idle capitulation or counter-intuitively efficient recuperation? Very pleasant, either way.

• The habit of eating direct from the fridge Liberal spontaneity or mere gluttony? Eating from the fridge is the sort of thing TV chefs own up to with all the enlivening gameness of a nonagenarian chasing his nurse around the bed.

• The habit of taking sugar in tea Tea is a fine vehicle for sugar, much better than coffee, because you can drink much more of it; it was to service our addiction to refined cane sugar that the British turned to tea in the first half of the 18th century. Dr Johnson—I’ve been to Lichfield and seen his teapot—could sink 25 cups at a sitting.

• The habit of tidying away what she is still using Tidy-minded or insane? It is known in the literature as Penelope Syndrome. This sort of idle busyness is characteristic of accidia, as I note elsewhere. A clutter of objects is both stimulating and psychically draining. Clarity of desk, clarity of mind. I worked for a man once who insisted on glass-topped desks in every office. No clutter, he said, rapping the desktop with his knuckles, no backstage. Only there was clutter and backstage, and now you had to look at it, and at your knees, while you worked.

• The habit of smoking A devil-may-care aid to concentration or a depressingly moderate fix?

• The habit of late nights For an agoraphobic, staying up late into the night is in a way a normalising event—everyone is at home on their own in the middle of the night. But it throws the delicate balance of the morning.

• The habit of Star Trek A puerile pass-time or an hour in space? She got this habit from me. She likes to watch The Next Generation late at night with a towering whisky nightcap.

All of these habits she deplores, at some time or other, to a greater or lesser extent. I have good days and bad days, she says; and it’s more or less a question of how the habits are distributed. I think. Or perhaps the way the habits are distributed is just how I know whether I’m having a good day or a bad day. Perhaps I shouldn’t think of it as bad days and good days at all; a bad day can lead to two good days; sometimes you need the bad days. Perhaps I should be thinking in terms of a week or a month, but then it’s the same, isn’t it? You need a bad month or two here or there.

Hunter Sidney agrees, by convergence. Of his occasional bouts of mild depression he says, they are an engine to something. There is always a bigger picture. You have to wallow from time to time.

I know this to be true, but crave the weightlessness of pure routine just the same.

![]()

Mrs Isobel Easter remarks in passing that she disagrees with my distinction between habit and routine as vice and virtue; surely, she says, you in your Idle City (as she insists on calling it) value the pleasant drift of habit for its own sake?

Perhaps, she suggests—as though proposing an alliance of convenience—there is an affinity of habit between Penelope at her loom and Polyphemus in his cave. Both are at loggerheads with the epic insanity of Odysseus. Think of Polyphemus with his introverted pottering ways, and of Penelope and her industrious subterfuge; he seeing to the wellbeing of his tiny sheep; she manipulating fibres smaller by several orders of magnitude than the most dextrous fingers.

—introverted pottering ways—

– Acis and Galatea, with Polyphemus

Alexandre Charles Guillemot

Habit might start off as a series of contingent and incoherent actions, but over time there is a gravitational sifting that brings them into some sort of mapped relation to the forces at the heart of existence: can you not, says Mrs Isobel Easter in so many words, read the shape of a life in the disposition of habits, just as you can infer the pull of planets, the organisation of a solar system, from the wobble of a star? The ascesis of an eremitical monk, for instance, is more a tissue of small habit than a big idea. Or again, you will judge a person—yourself perhaps—to be kind, or indifferent, or vindictive by extrapolating a hypothesis to that effect from a small number of unlinked actions; you do not deduce the valency of these actions from a known disposition.

I take it from this—although she does not state it thus clearly—that she regards habit as the temporal expression of the a-temporal logic of life. Or, more precisely, that the welter of discontinuous action in a life will come to be gradually but inexorably polarised.

However, I am forced to conclude that she has not grasped what it is I understand by routine. A routine of the Failed Life is not an efficient means to an end, although it might also be that; it is no more than a given set of patterned habits. A test of a routine would be that certain habitual actions would not fit, or would be disruptive. By contrast, you can just chuck habits one on top of the other, until you die.

A routine is a satisfying, complex object; a habit is an erratic pulse.

![]()

Having said that, there may be some truth in her assertion, if I have understood it correctly, that what I describe as habit and routine are no more than different stages in the life cycle of action, different aspects of the same thing.

There is a fresco by Pinturicchio (detached from its wall in Siena, and now in the National Gallery in London) of Penelope at her loom.

—different aspects of the same thing—

– Penelope at her Loom

Pinturicchio

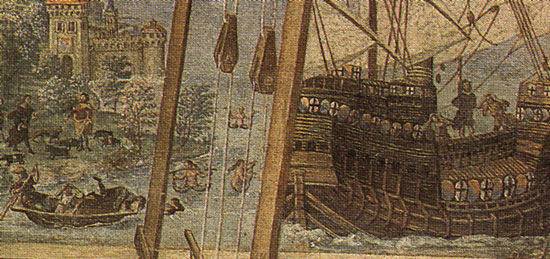

She is illustrated fending off a somewhat ungainly suitor (Antinous? or is it in fact Telemachus?), while through the window at the back of her chamber her husband can be seen:

(i) standing, immune, on Circe’s shore (his immunity contrasting with the involvement of the chief suitor, who has somehow contrived to wander inside the perspectivally approximate loom) and

(ii) tied up on the deck of the ship against the seductions of the sirens bobbing around in the water.

—standing...bobbing—

– Penelope at her Loom (detail)

Pinturicchio

He is also sometimes read as the figure stepping through the door at the back right.

Polyphemus is not in the frame, but you could imagine a companion piece, of Odysseus as seen through the cave mouth, navigating Scylla and Charybdis, or hard-pressed by Poseidon, or in the jaw of some other mytheme.

Penelope is weaving a burial shroud for her elderly, not-yet-deceased father-in-law, Laertes. The ruse of the shroud is recounted in Book II of the Odyssey by Antinous; the compression of events in the fresco is more acute even than it initially appears. In any case, allowing for the vernacular retelling to which Pinturicchio seems to have been working and the traditions of moral exposition to which those vernacular retellings were tied, it could be said that Penelope’s brief moment of covert resistance is here eked out and emblematised into a habitual disposition of constancy realised as a habitual action.

The tidal movement of Penelope’s weaving stands, as Isobel Easter notes above, in contradistinction to Odysseus’s ballistic progress: his vector, framed in her window like a picture, is highly particularised and unrepeatable. She, meanwhile, manoeuvres in a tight psychic space (a domestic space, specifically: the loom as big as a room) through a series of circular, repetitive and ultimately productive gestures. What she produces is not a woven ritual object—the key to her action is the unmaking, not the making—but a sort of spun yarn or narrative carapace designed to protect herself, like some voodoo incantation spread over days and weeks.

—you do that voodoo—

– Penelope at her Loom

French or Franco-Flemish, c.1480-1483

She has learnt, at one level, to organise the flow of her domestic situation through the application of industrious habits, at the cost of a certain (spatial) disruption. At another level the weaving/unweaving are companion actions within a routine, a systole and diastole, a contraction and relaxation. The unpicking is not so much an entropic relaxation (Hunter Sidney’s ‘occasional wallowing’) as a beating back against the current; nevertheless, both creation and de-creation, systole and diastole, come under the umbrella of a meaningful routine.

![]()

Hunter Sidney reminds me that Penelope was weaving a funerary shroud, and that this would have been a plain (white or grey) cloth. I had been about to speculate1 that it must have been ornamental, on the assumption that the suitors would have more readily noticed degradation in figurative design; and to remark, on the basis of that erroneous conclusion, that the habit of ornamentation is the salvation and delight of the domestic sphere.

Penelope’s purpose, however, was more focussed, more resolutely dour. Her struggle is no less murderously intense than that of Odysseus, but it is certainly less fun. I had always imagined myself out there, through that window on some strange shore, battling the gods in a blaze of action, but now find myself, like her, weaving mordant ornamentations in the confines of a disrupted space against the importunate attentions, the beggared fingers, of the chthonic hags of this world: time, memory, and loss.

![]()

At around the time of these conversations with Mrs Isobel Easter about habit, I was introduced by Clarke to an almost wholly unknown local celebrity, a blinded Cyclops in his cave if you like, old Nestor Spinetto, the expatriate Argentine who had managed Norbiton FC in their days of teetering glory in the mid-to-late 1960s and again, for a year, at the time of their demise in the late 1980s.

Nestor lives in a small flat in the Cambridge Gardens adjoining the Cambridge Estate.

—Cyclops in his cave—

– Cambridge Gardens, Norbiton

He is not a Cyclops, but he is blind, the aged crumbling remnant of a bullish man, shuffling tracksuited and slippered around his living room like a deep sea creature in an aquarium. He has sunken cheeks and a big purpled mouth with which he seems to pick up vibrations in the ether; it twitches when anyone speaks. He leaves his flat only occasionally, perhaps once or twice a week, to sit in one of the cafes along the Kingston road and talk to the Italians and Poles—people who understand the game—about last night’s match.

Not that he is afraid of the outside world, says Clarke, merely indifferent. He is not only blind but exiled, forever estranged from his homeland: there will be no homecoming. He sits in an invisible place, a place known only by touch, sound, smell; where the predominantly aural geography, the rumbling of the plumbing and the noise of the television or the children returning from school in the apartment downstairs, define the elastic and interpenetrating walls floors and ceilings of his space.

That space, to the eye, is grimy, tobacco-yellowed (he smokes thick black cigars in short bursts, keeping one going for the morning, and one for the evening), dust everywhere overlaying grease. But it is orderly enough. Someone from social services comes round to cook and clean for him each morning, but he has no patience for vacuuming or detergents, so she mostly just tidies away for him, replaces batteries in his radio, finds things which have gone astray, and talks through from the kitchen to him while she works. She is Peruvian or Bolivian, Clarke doesn’t remember which, and she and Nestor talk in Spanish; his speech massy, ornate, sinewy, dark, like a Pollaiuolo bronze.

—massy, ornate, sinewy, dark—

– Hercules and Antaeus

Antonio del Pollaiuolo

We find chairs to sit on and Clarke leans forward to engage him in conversation. Nestor has groped his way back into an armchair dotted with crumpled and forgotten antimacassars. On a small table at his right hand he has a radio, his cigars and ashtray, a coffee cup. When he speaks he speaks only to Clarke, never to me.

I sit and look around at the yellowed craquelure of this invisible interior. What is our business here? I am curious for a number of reasons about the habits of a blind man, but this is not our stated purpose and in truth you do not learn much about a person’s habits by paying them a visit. Clarke wants me to meet Nestor pursuant to an insane project of his own to resurrect Norbiton FC next season and employ Nestor as manager. I am pencilled in for left-back – so often, according to Clarke, a troubled mischievous thorn in the flank of both teams.

Nestor is reluctant to commit himself, not, I infer, because he doubts his own ability as a blind man to manage a football team, but because he doubts his capacity to give a toss for the duration of a season.

However, in the course of a brief discussion about how a blind manager might handle a match or training session, he makes an interesting comment on the interrelation between, as I understand it, routine and repetition. He says that as a coach you are always skirting the object of your attention, closing in on it, circling it. All of the routines of training are designed to capture and then opportunely release something which no one can see, no one can point to, no one can name. They grope for a term, he says—team spirit, they call it, flowing football, total football, in Greece they called it divine madness. Draw your own conclusions. If you have ever played football, you know that from time to time Football emerges from football.

He picks the stub of his cigar from the glass ashtray and lights it. How do you make this happen? he says, puffing grandly as though intoxicated with the fumes of his own Pythian rhetoric. I do not know. Nobody knows. But it is what we are searching for, more than winning or losing. You do not worry, almost, or you worry in a different place, if you lose the game. If you—your team—has played on this plane, you know it, and you are happy.

And so in training, you have your routines, your drills, and you repeat and you repeat and you repeat until the blood seeps from their boots. And why? So that they can forget. Their muscles remember, perhaps, but they run on to a football pitch as through on to the planes of forgetfulness; you, as a trainer, a coach (not a manager); you are their Charon. You ferry them to them land of forgetfulness.

And there they are, or can be, at peace. They go up through the gears, the machine rattles, it shudders; and then it breaks some mystical barrier and all friction of action and running and thinking dissipates, and for a short time there is peace. Everyone has time. The goalkeeper at peace in his area, he plucks balls from the air and bounces them on the turf and spits them back upfield like an immovable vortex of physics; and those balls find the players at peace and in full possession of themselves; everyone has the time they want, they can move or not move, trap the ball or saunter into space, and everything they do means something. Has purpose.

And you, as a manager at a time like this, much though you rejoice, you perceive it could be so much more; the players, you imagine, could disentangle themselves from the topologies of pitch and ball, from their relative positions, could interrelate at the level of the forces at play; nameless, unnumbered players, interlacing pass and movement derived from the molecular interaction of the teams – and he points to his temple, or is it to his eye, with that arcane manager’s gesture, as though we are party now to the Masonic secrets of all managers. As though thinking the game into being from first principles. Inventing the game. A one off, for all time.

When we leave him, his vision of mystical lift off at the Rec. smouldering like Troy behind us, Clarke says, 'you know at NFC he played a clattering 4-4-2. We were butchers'.

![]()

There are spots on the face of the earth where no human sound is ever heard – no car, no plane, no buzz saw. Some years ago there was an attempt, I do not know whether successful, to enshrine the inviolability of these spots in international law. No human would ever visit them, no plane would be routed over them, no road built near them; no one would hear the alien silence, even though it would be created for us, would only exist for us, and then only as an idea: it would be enough to know that it was out there, somewhere.

The point that Nestor is groping mystically towards, if I can summarise it, is that there is just such a point of balance in life that is outside habit and routine, but is held in place by it, created by it, defined by it. An emergent point of balance. This point is not all of life; it is certainly not all of the Failed Life. The Failed Life is more about the routines than this point of balance, or at least it is about their systemic interrelation. But the point of balance is, if you like, the hypothetical at the heart of the machine, the ambiguous singularity you will never see—it will only ever emerge in the form of a practice or pursuit of some description. It is non-material, but it is not mystical, spiritual; it is conceptual, it is rooted in understanding. Those footballers running around out there in the warmth of perfection: they know they are playing well, are in the zone; some of the spectators know too, and others do not, they cannot all distinguish or discriminate.

In leaving my job, I realise now, I risked being engulfed by a cascade of habit—and for a few months, the Star-Trek months, this is what happened. But on leaving my room and creating the Ideal City I moved, temporarily, into a world beyond the easy reach of habit. More or less everything I did or touched had to be placed in the systems of my life by hand, as it were. Everything was, not new, but newly interrelated.

With the work in the gardens of Mrs Isobel Easter and Tony dell’Aquila, for instance, habit did not exist. I did not know enough. Ingrained habit in a craft invokes pockets of fluent skill. These I did not have.

Perhaps, were I producing a garden from scratch, on a bare piece of earth, nothing to guide me but the fences, the nature of the soil, the facing; I suppose in that case old habits of thought would be allowed to reassert themselves; I would perhaps think too much about the history of the plants, their provenance; I would build something ungainly and unattractive, old fashioned, ponderous, verbose; it would have parterres and grottos and rooms; it would stink of the past.

But I am working to a clear grain, in a pre-existing place, and my hourly conversations with Mrs Isobel Easter, in particular, generate enough clear direction for me not to have to consider the end of my actions. In this way gardening has become, for a short spell I hope (I do not especially enjoy gardening), a paradigm of routine in the Failed Life: a routine that presupposes no end (although there may be an end in view); a working from, rather than a working towards; one that cannot be analysed, therefore, in terms of its efficiency, nor the contribution of its component parts easily assessed. This is not to say that there is no discriminatory logic, but its terms are internal; the Failed Life is intended as an internal logic of existence.

![]()

Two or three days after our meeting with Nestor, I find myself with Clarke, Hunter Sidney and Nestor at the top of Madingley Tower, in Clarke’s isolarium, waiting for the sun to rise over Coombe Hill. It is a cold morning and we are layered against the cold; Nestor has on a QPR bobble hat that only a blind man would wear. I have made a thermos of coffee, and share it around.

Dawn is a predictable event but the sunrise is not. The sunrise in a city is haphazard, squeezed out in some ad hoc compromise between brick and sky, old world and new.

While we wait, Hunter Sidney tells me a little more about what he calls his Gethsemane months.

He says that what he was experiencing was a reconfiguration. He still went to work every day and sat in his office like a heap of cold embers in a grate; he spent his weekends alone in perplexed and motionless anguish. But the whole experience, like the conflagration of love that had engendered it, swept away for a time the habit of his life.

Habit, he concludes, is a delicate ongoing carboniferous sedimentation, dispersing to invisibility in the approach of a storm, but settling again relentlessly once calm is restored, heavier and heavier, hardening imperceptibly, until it fossilises its incumbent in an attitude of forgotten Pompeian pain. It becomes, at this stage of development, mere activity, a reflex emptied of all desire or joy or attention.

Whether you can ever make anything of this remnant alone is a question that Hunter Sidney was not called upon to answer; because what he was developing in the daily-returning eye of that swirling storm, as he sat in the dawn light reading Seven Pillars of Wisdom2 and drinking tea for an hour and watching the day take form, was the kernel of a routine, one that would ultimately resist the return of untutored habit, based as it was on clarity, necessity, and understanding.

Thus from that period of emotional reprogramming emerged, by way of these islands of respite, the anti-literature; to invert our imagery, the habits that had buoyed him on the surface of life were burnt away, and he was free to begin his long slow determined descent to the Deep Net, where he now resides.

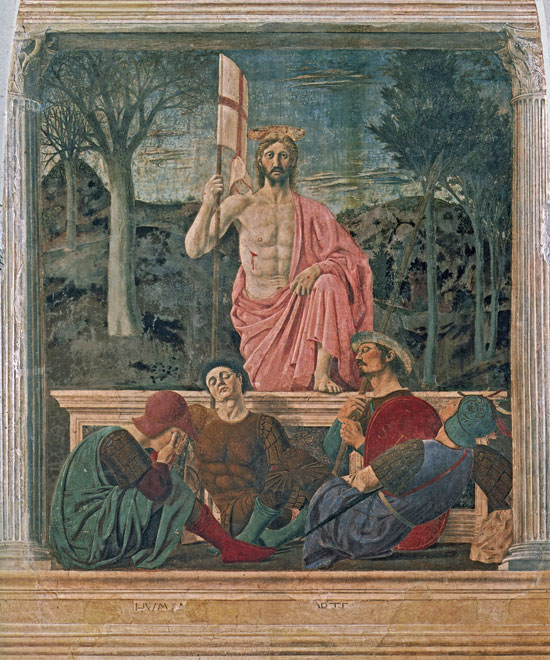

We waited a long time and were preparing to give up, but the sun finally hauled itself over the house tops on the Coombe Hill, glanced at us where we stood glumly worshipping, and then careered upward towards a bank of cloud approaching from the west. We waited for another few minutes until Nestor declared, perhaps in pity, that he could feel it on his face, and then went back to bed, or to our morning books, as habit might dictate.

—feel it on his face—

– The Resurrection,

Piero della Francesca