Epistemological

—psycho-perceptual mechanics—

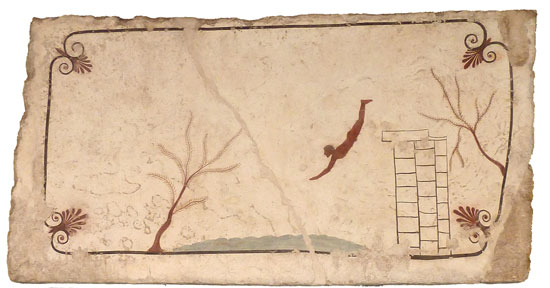

– Diver, Paestum

There is no such place as Norbiton Garden City.

While this is probably for the best—the concept of Garden Cities being so much junk civic DNA—Norbiton nevertheless has a residual affinity with allotments and gardens.

Gardens, like sleep, are places governed by a peculiar psycho-perceptual mechanics.

They are at once concentrated, private, enclosed; and yet diffuse, exposed, open. There are walls, but there is the open sky; there is the weight of physical labour necessary to maintain their shape and purpose, and the intellectual and practical need of the gardener to know the garden, plant by component plant, to develop a body of know-how; there is the sensory tickle of breezes and perfumes, the scintillations of light and droplets of water; there is a purity (weeded beds) and a compacting (the logic of garden rooms), but also a proliferation, a fecundity, a bolting.

—intellectual needs of the gardener—

Knowledge in a garden—of a garden—is part practical know-how, part taxonomical grid, part aesthetic case-study; a flower or a plant as object of knowledge passes easily from one way of knowing to the next as we select, dig, admire. We wheel our barrow, hoe out weeds, take cuttings, collect seed. Generations have done the same before us, turned the year over like composted experience, bent on the production of knowledge.

Thus it is that in a garden, under conducive circumstances, if you are responsive, sit quietly, listen carefully, your subterranean existence can quietly assert itself. It is not that you do not worry, in a garden, about your daily occupation, your want of success, your financial predicament; it is that these objects of knowledge are, or can be, reworked or reconfigured, cracked like nuts or carbon chains, made strange, volatile, succulent.

We remember, as the outcome of this chemical procedure, and as though after a long amnesia, what it is that we actually desire, love, or hope for.

![]()

Perhaps I can restate that as a general proposition. Under certain conditions—in a garden, in the Ideal City, in a garden of the Ideal City—objects of knowledge achieve weightlessness. Or, at the very least, a considerable buoyancy.

—buoyancy—

– Painted Garden of Villa Livia, Palazzo Massimo, Rome

What we know, in other words, seems so light, when we are able to inhabit it. You can climb inside a city or a garden. We experience them as having extension and duration. We no longer feel a single neuron firing at the thought of them; rather our neurons are flickering firestorms of activity.

This is true, as I say, of certain classes of object. A city or a garden, but also a book you read and re-read, a painting you stand in front of, music you listen to or, especially, play; a person you talk to, make love to; a day in a given season—early spring, mid-summer; anything, in short, that is or can be roughly iterative.

Under these circumstances of approximate and varied repetition, the object of knowledge—which you are from time to time actually inside—is a thing of volumes, not masses. Volumes are airy and weightless. Masses are monolithic.

Hunter Sidney disagrees.

—Hunter Sidney Disagrees—

He says I am too freely conflating two versions of garden: one where the garden is known, and one where it is experienced. These are to an extent mutually-exclusive determinations. In order to be known—grasped—it must be translated into a knowable form, a mentally portable object of some sort. It must, in short, be made available to Thinking. But that is all.

I do not contest any of this. Hunter Sidney is simply not seeing all around the object of knowledge I am attempting to shape for him.

We are as it happens in a garden, and I am talking Hunter Sidney through my theory of knowledge.

The garden is dell’Aquila’s. Dell’Aquila is not here. It is secluded and peaceful, and warming gently in the early spring sun.

I am doing some sketching and thinking about the design of the garden. Hunter Sidney is sitting on the wall with his hands in his pockets.

As I sketch, I direct Hunter Sidney’s attention to the sensory objects of knowledge of this garden.

The breezes, for instance, are multiple, conversational; flowers nod and rock in the air as though moved themselves to contemplation; the warmth of the sun on the walls and slabs of stone sets up convections on which insects, ungainly or sprightly, set sail like Phoenicians on the Mediterranean trades in the early dawn of new civilisations; there is the sound of water trickling into a fishpond, the fish holding themselves still in the water as though humbled by the mercy of the new season; and there is also the building site diorama down in the corner where dell’Aquila is building his folly: a blue tarpaulin lifting at the corner in the wind and under it a stack of bricks, a caked orange cement mixer pointing skywards like a howitzer silenced by armistice.

So far from sensory divagation, I suddenly intuit, the garden has properties of sensory exactness. You are encouraged to perceive the finer structure of things. Perhaps what I call lightness is a sort of mental mobility.

—finer structure of things—

– Painted Garden of Villa Livia, Palazzo Massimo, Rome

Put like this, it is easy to see why gardens are traditionally apt locations for love and contemplation. In a garden the things you know—personal success and failure, for example—become toys of the mind; they can be reconfigured.

This fine structure, more or less immediately available, is the key to buoyancy, volume. And yet it is not distinct from the garden-as-known.

What is a garden experienced, after all, if not something known? The quality of knowing may vary, but the fact of it does not. I can hold a cup in my hand, drink tea from it; or I can look at one in a museum behind glass, or remember having done so. These are all facets of my knowledge of the world.

Counter-intuitively—and this is my point—the cup as held in my hand weighs less as an object of knowledge than the cup I hold in memory.

Hunter Sidney looks at me blankly.

Or not a cup (a bad example, I concede) but a woman, let’s say. And at this Hunter Sidney is finally convinced—although he does not say so—because his great love, the woman he sacrificed everything for, whom he has not seen for twenty years, but who lives half a mile away, is nothing more than a fading neuronal pattern of immense and contradictory weight.

![]()

To be clear, I, like the Florentine Renaissance, do not suffer from epistemological angst, but not for the same reasons. In my case, my humours are too sluggish and silted to respond to such a febrile stimulus. I am temperately conscious both of the flickering importunity of the sensorium and the stolid continuities of my identity; the one does not threaten the other. I am a saturated, loggy creature, a claggy mud god at the roots of the Ideal City. I think that after I die I will persist like bits of fired clay in a cakey layer of soil, not eternal, not sentient; just hard to get rid of.

No. My epistemological fears are all intellectual; I only find gardens, the sensorium, perplexing in the context of the Ideal City, because I am, like most people, at my happiest when I least exist, and I find that I least exist in the sensorium.

The Florentine Renaissance does not, on the face of it, suffer even this mild anxiety. Gardens in the predominantly urban painted space of the quattrocento are merely the defining spatial unit in certain classes of image: an annunciation, for instance, or an agony. It is a non-deformed space; it is a space that defines the logic of a given narrative point.

As an achievement, however, this can be read as one solution to the, if not strictly epistemological, then perceptual crisis set in motion a century earlier by the peculiar work of Giotto.

Giotto is notable for the three dimensional solidity of his figures, and whatever else that means it represents an irruption of weight into an art that is not set up for it. By weight I mean something more than three dimensional solidity, although that is a large part of it.

If weight, as distinct from mass, is defined by the force required to oppose it, then a painted object will have, or appear to have, weight if the architectonic resistance is inadequate to it.

—architectonic resistance—

– Palm Sunday,

Capella Scroveghi, Padova — Giotto

So while the boys on Palm Sunday in the Capella Scrovegni in Padua can plausibly bow and bend the branches of the trees they are climbing against the infinite blue sky, because both tree and boy are convincingly round objects set against a spatial nothing (in that there is no such thing as sky and a field of blue will do as well as the 'real' thing), the great earthbound saints and sinners do strange things to the representation of architectural space, as for instance here:

—strange things—

– Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple,

Capella Scroveghi, Padova — Giotto

Joachim is expelled from the temple, not into a putative Jerusalem street, but into an abyss of gravitational chaos, as though, I note elsewhere, he is being thrown out of an airlock on a crazily implausible spaceship.

He will only finally drop to earth as it were in the Ideal City. Linear perspective is sufficiently wiry, sufficiently well-engineered, to act as a counterpoise to the colossal bulks of these saints and virgins. According to this interpretation, the construction of an illusory space is a way of situating heavy objects in a way that does not offend (although it may still astound) our perceptual equipment.

As for example, here:

—strange things—

– Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple,

Capella Tuornabuoni, Domenico Ghirlandaio

Ghirlandaio, at the end of the quattrocento, has retained Giotto’s definitive organisation of the episode, down to the slightly pained expression on Joachim’s face. The architectural and spatial system, however, is now an adequate counterbalance to the figural groupings. The handling of rational space has, for a while, overmastered the challenge of bodies.

![]()

Hunter Sidney has been pondering my epistemology, and now tells me drily that what I am describing as a potential property of knowledge—its buoyant volume—is in fact no more than a property of garden.

The properties of knowledge are not heavy or light, voluminous or massy, in and of themselves. They can be one thing or the other: it depends on their context, on how present they are to us. In a garden, certain objects are rendered more present. In the same way that we hear our pulse beat when we lie in bed, so are we aware of the acuteness of certain things we know—former jealousies, for example, former pain and suffering, the lineaments of our former selves – only under certain conditions.

Memory, in general, is thin, he says. Or in my terms, buoyant, volatile. You cannot be sure of anything that lies in memory. It is only a faded shorthand. If you try to grasp it solidly, it vanishes.

But it is also persistent, like a malignant gas. You cannot shake it off, or know its extent, or chart its strange interactions.

David Hume, in relating the anxiety which his epistemological scepticism from time to time brought on, says that all his doubts fell away when he took himself from behind his desk and engaged in the common affairs of life. Not only that, but returning later to his desk, his former anxieties seem shallow and weightless1.

But Hume was not proposing a solution. He was noting a discrepancy. And whether the garden is a bower of forgetfulness or the office of memory, is merely a matter of opinion.

![]()

Hunter Sidney, having exhausted his observations, wanders into dell’Aquila’s house, leaving me in the garden to sketch. I am trying to find a way to balance the new structure of concrete and granite and marble yet to take form at the bottom of the garden, with the garden itself, and am not finding it easy.

This is partly in the nature of the challenge I have set myself. I am designing a gravity garden. It strikes me that while the structure of a Renaissance garden in some sense reflects the structure of Renaissance thought, mapping out a taxonomically precise yet continuous space, so the garden of renaissance Norbiton should reflect our own structures of thought, and these, clearly, are gravitational in nature.

What does a gravity garden look like? It has, consciously or not, been done before. There is, for example, the Villa Lante north of Rome, where the basic configuration of the garden is gravitational.

Or there is the Hortus Palatinus, which hung suspended like the Gardens of Babylon in the middle air.

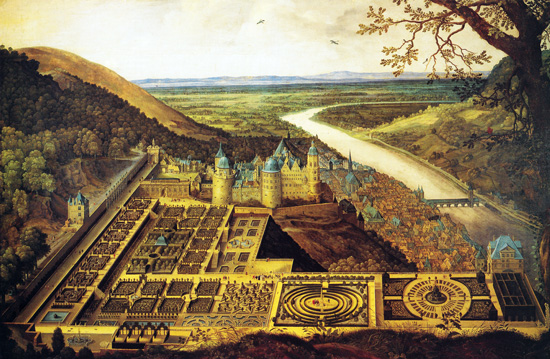

—in the middle air—

– Hortus Palatinus

Jacques Fouquières

Our scale is not so ambitious, but our coherence is perhaps more explicit. Our own gravity garden will be laid out in accordance with the following ample principles:

- Gravity will be variable but coherent by region. Whether gravity is strong in a given region (a region flattened to the ground, rolled, mowed) or weak (blossomy, airy, dandelioned), it will nevertheless be consistent in that region.

- The gravitational pull of a garden object will be both actual and perceived, and no particular priority will be given to one over the other. Thus the summer house could be considered actually massive (made of marble, granite) or apparently mass-less—for example a volume ornamented with tendrils.

- The architecture of the garden—it follows—is to be considered in section as well as in plan. There will be layers. As for example: bedrock, earth, undergrowth, heavy gnarl-rooted plants, quick climbers, mobile grasses, birds both in their nests and out of them; insects etc. [earthbound (crawling things), massive (bumble bees, dragonflies) lightweight (butterflies, hoverflies) imperceptible (mosquitoes), intermediate (beetles, ladybirds, honey bees, spiders) and so on]; upper airs, ethers, spirits.

- Some of the garden elements, the heavy ones typically, cannot be moved—trees, house, summer house (if that is a heavy element). These will in the first instance dictate the grain of the gravitational system.

- Since there will be zones of varying gravity, it further follows that there will be intermediate zones, zones which climb precariously between the wells of gravity. These will be the pathways.

- Gravity in the gravity garden will depend on meteorological conditions and variable light. A garden in spring will not obey the same gravitational rules as one in winter; one in sunlight and breezes will be different from one in wind and rain.

![]()

I have decided that as part or subset or room of the gravity garden, I wish to construct a rain garden.

A rain garden is designed to structure rainfall, when it comes. Certain leaves husband water and let it go in large drops at a given rate; others curtain it down in rivulets; others shower it around in fine sprays. I saw Monty Don in the Brazilian garden of Burle Marx pour water on a leaf which repelled it like a magnet.

There is thus a gravitational structure to rainfall and its aftermath, one which is open to artifice. There are, moreover, possibilities for handling the run off in various ways, channelling it, dispersing it, concentrating it in clays or draining it away through fine sands.

Somewhat perversely, I wish to build the rain garden in Mrs Isobel Easter’s garden.

I want to build the rain garden in Mrs Isobel Easter's garden (without her or her husband's knowledge) for two reasons. In the first place, the Easter garden is conducive—there is a lot of overhead vegetative plumbing space to play with. In the second place, and more importantly, my conception of a gravity garden at dell’Aquila’s is in fact only part of what I am now starting to see as a gravitational system of gardens in Norbiton: Ideal City as a whole.

If different gardens exist in the minds and memories of the perceiver as objects of knowledge, objects which have the summational power of, for example, the spines of books, then it seems to me consistent with the structure of the Ideal City that its gardens should be at once visible and invisible—visible to initiates and non-initiates alike, but properly visible only to initiates—citizens, in other words.

Thus if I am anyway willing to stretch the boundaries of the Ideal City to encompass dell’Aquila’s garden, I see no reason why we should not make of all our collective gardens and green spaces one coherent space—not contiguous or connected, but coherent as a mental object. To this end we would build the gravity garden, the rain garden, a sun garden (the isolarium—a few or possibly no plants), and whatever else we can think of for Hunter Sidney’s back garden (which I have never seen), for old Sol’s, for Emmet Lloyd’s if he is willing. I do not know if Cannoner has a garden. I do not, but could imagine a tiny window garden of microscopical alpines and mosses and lichens.

Norbiton Garden City may not exist, but there is no reason why Norbiton: Ideal Garden City should not.

![]()

Hunter Sidney comes back from casing dell’Aquila’s house. I do not know it at this point, but he has pocketed an object that he found in dell’Aquila’s living room, a photograph in a frame of dell’Aquila with Isobel Easter and some other people (including Kelley), taken some twenty years previously.

This theft is, from an epistemological perspective and in the light of our previous conversation, interesting.

Hunter Sidney has had no photograph of Kelley’s wife, nor a sight of her, for twenty years.

Not only that, but the jealousy which prompted the dissolution of their affair was precipitated by Tony dell’Aquila.

Jealousy is an epistemological crisis, not resolvable to what a person did or did not do, but involving unknowable and unrecorded intentions, untraceable movements of the minds. And a photograph is only one sample of a person taken across a multitudinous dataset, not so much a resolution of memory as a hypothesis, a starting point.

All of which would suggest, to my snooping soul, that Hunter Sidney's photograph is a prompt and focus for action. Whether that action comprehends a confused sense of somehow reclaiming the object of his obsessive devotion, I can hardly tell.

![]()

I have noted that the quattrocento Renaissance did not do epistemological doubt, as such; but the same is not true of the French Renaissance of the sixteenth century, and in particular of Montaigne. Montaigne’s great trick—of dismantling our certainty not by attacking the philosophical grounds of that certainty, but merely by pointing out, repeatedly, destructively, you might say juristically, the mutability of our opinions, both individually and as a species—has the effect not only of detaching us from our moorings, but of setting up a mutual gravitational system. There are no fixed bodies in this lower world, he seems to say. We and our objects of knowledge are in bemused rotation about each other.

—bemused rotation—

For a glimpse of this represented in paint we need to look, not to Florence or Rome, but to the Netherlandish painting of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Netherlanders, it has been observed2, focussed their visual attention on the discrete object, rather than on the narrative pattern into which those objects fall. While the Italians painted istorie, drama unfolding eternally in infinite space, the Netherlanders—the van Eycks, van der Weyden, Robert Campin, Hans Memling, Bosch, Pieter Bruegel—painted stuff: objects talismanic or plain-speaking, ethereal or domestic.

What, after all, is the garden in The Garden of Earthly Delights if not a container of strange objects warily circling one another, a quizzical loop in which the viewer is inevitably involved? And what, we might continue by extension, is time spent in any garden but a dalliance on the edge of perceptual reason?

—dalliance on the edge of perceptual reason—

– Garden of Earthly Delights, left panel

Hieronymus Bosch

This, more or less, is the sort of garden I want to make. One which does not pretend to completeness, order, symmetry, an end point in a logical chain. Those things have had their time and place in the desires of men and women. The garden and gardens I wish to set up for Norbiton: Ideal Garden City are ones which stake their claim to order on a creative leap in medias res—a garden which is nothing more, to put it another way, than a stone kicked in idleness over a precipice: how it bounces, what it dislodges, where is comes to rest, cannot be predicted except in the most general terms, but those terms are sufficient to guide the attention not only of the gardener—returning to my theme—but all who visit the garden.

![]()

Usually when we try to verbalise what we feel it comes apart in our hands. Like a parchment or papyrus brought to the light after millennia of inaudible and invisible eloquence, our clumsy attempts to unscroll our mental objects of knowledge and read their contents off to the world at large, or to friends or intimates, are blown away, words and dust scattering on the unyielding breeze.

Mental objects, as I say, are hard to catch hold of. This catching hold of is the business of art, of scholarship, of science; the mathematics of quantum physics, to take an example, are an object of knowledge (or form of inquiry if you prefer) for capturing, thinking about, subtleties of particle interaction or configuration which we cannot even imagine.

The structures and forms of the ideal city serve a similar purpose. A city and its institutions catch hold of a certain quality of experience which are not easy to verbalise. They are sensory nets. And the gardens of that city are, I would hazard, a special sort of perceptual array. In a garden you are in the city, but you are not; you are on the outermost spiral edge of the strange object we have created, where its gravity is weakest, in its sensorium; and here, the component objects of knowledge of that city are commensurately light, can be nudged and bobbed into place, or rolled into position—can, in short, be thought; and, to a degree, expressed.