supplemental notes, pt.ii

...monstrous Etruscan effluent...

Effluent or tonic, depending on your viewpoint.

The Etruscans were a lost, or rather submerged, race, who were known to the Renaissance from Roman accounts of their barbarity.

The Romans adjudged them piratical, terrorising the Tyrrhenian Sea; they were given to luxury, indolence and vice, to torture of their captives (whom they would bury alive bound face to face with decomposing corpses), and to mysticism—many Roman religious rites were derived from the Etruscans, and even in the days of the Empire they were still employing Etruscan haruspices to prognosticate with livers. They used a language we can barely decipher, which appears not to have been Indo-European. This would argue either an unfashionable movement of peoples (Herodotus has them coming from Lydia) or a pre-Indo-European remnant, like Basque, a knot of resistance to the steady march of the farmers (in the disputed account of Colin Renfrew in Language and Archaeology 1990).

But whatever else they might have been—and needless to say, we have not seen their own account—the Etruscans were builders of cities. The Etruscan state was not a state but an insouciant federation of twelve great cities. It was their division in the face of Roman drill and focus that led to their gradual downfall and submersion beneath the Classical waves. Civ Clarke tells me that, once you are attuned, you still see Etruscan faces walking the streets of Rome, those long chins and almond eyes and deep smiles.

Each Etruscan city was balanced by its own city of the dead, a necropolis typically built on an adjoining hill or ridge, the architecture of whose tombs was modelled on the houses of the living: a domestic architecture of the dead.

In the necropolis at Tarquinia there are number of painted tombs depicting the sort of activity, I take it, that Etruscans enjoyed—hunting and fishing, games, banqueting, fucking each other, and music. D.H. Lawrence wrote a potty book about the Etruscans, called Etruscan Places. He was, unsurprisingly, a fan. And in fact they don’t seem so monstrous to me, but then I am not bound to the body of a corpse, and invited to meditate on putrefaction.

—don't seem so monstrous—

– Tomb of the Triclinium Tarquinia

...the resemblance...

I do not want it to be understood from this that I was in love with Veronica de Viggiani. I was, however, strongly reminded in her presence not only of the former lover in question, but of a particular region of mental geography, if you like, which I had once known well but which had recently been submerged, taken on the status of mythic land, a hazy island on the immense ocean—and that region was, I suppose, associated with love. She reminded me of love.

It was, to put it differently, as though an aged Marco Polo, long since returned from the East, his limbs creaking with rheumatism, dwelling mostly on the ruin of his vast ambitions, the modesty of his estate; as if he were now shown a good map of the lands of the Great Khan. He would trace with a hesitant but wholly absorbed finger the journeys he had made, recall the cities he had seen, marvel at how much he had forgotten. And if that map were a person? An acquaintance from that land, someone who could stand witness for him that what he had seen was true, that what he had related had in fact fallen out as he told, whose own memory varied from but stimulated the workings of his own? His general idea of the East, this complex mental token, but a token nonetheless, would be analysed out again into its constituent elements: the East, in his head, would live anew.

Veronica could neither bear witness for me that my supersaturated love had been well founded, or returned; nor could she show me a version of the evolutions of that story. But she did remind me of the specific draft of love I had taken. If, I now realised, I had cheerfully disregarded the want of love in my life in recent years, it was because I remembered love only for its generalised chemical properties. But any given love will in fact be stamped with a unique signature. This, I suppose, is why when an affair ends badly you see the beloved several times daily for weeks, months—in my case years—after, in glimpses of strangers rounding corners, the backs of distant heads, a brisk gait or flick of the hair at five hundred yards: the whole world is bent to the specifics of your case. You do not hallucinate your love, your bereavement, you merely project its overwhelming veracity, as though your head were a battleship crewed by missionaries.

So, not in love. No reason to be. But contiguous to it, suddenly aware of its absence.

...proud of the operation...

Later, Clarke disabuses us of our admiration. He has been to Cobham several times, he tells us, and talked to the nurserymen. The computer manifest bears little resemblence to the world it purports to describe.

It seems that the software systems they have in place—what Emmet calls the plantware—are not robust enough to be reliable. When the system says a pallet is ready to ship, some gnarled old nursery hand has to potter out there with a spade over his shoulder and ‘verify’ that the pallet is in fact ready. Typically, however, it isn’t, but some other pallet is, and the nurseryman will just ship that instead without bothering to notify the system. The system itself further corrupts and misplaces even the inputs it does receive. It is always in arrears, a poor shadow of reality.

Emmet and his father (or anyway his father’s old retainers) are running parallel businesses, only one of which is making money.

...a veduta of that same square.

The view is from the North. Piazza del Popolo can be regarded as the gateway to Rome, the first bit of the old city the visitor on the Grand Tour would likely see (if we except the Milvian Bridge).

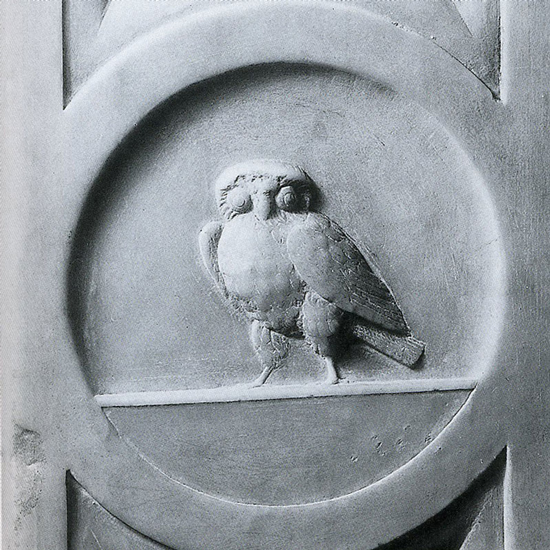

I am, I realise, going to make too much of this, but the doorway that separated Isabella d’Este’s studiolo and grotta in the Palazzo Ducale in Mantova, designed at some point prior to 1505 by Gian Cristoforo Romano, was a repository of emblematic meaning, carrying images of three of the muses (Euterpe, Clio and Thalia) and Minerva, and six of associated animals of various sorts (an owl for Minerva, a peacock for Clio, and so on).

—an owl for Minerva—

– doorway, Palazzo Ducale, Mantova

—and so on—

– doorway, Palazzo Ducale, Mantova

A door, I am going to speculate, is akin to a directional node in a unicursal labyrinth. It does not necessarily mark a forking of the ways (although it might very well), but it does mark a passage from one state to the next. Hunter Sidney talks of the ornamental border separating cells of a single life; I wonder if he realises that he himself (as I suspect) provides the emblematic device on the hiddenmost interior of Mrs Isobel Easter’s domain.