Iconoclastic

—inscribe ourselves on the world—

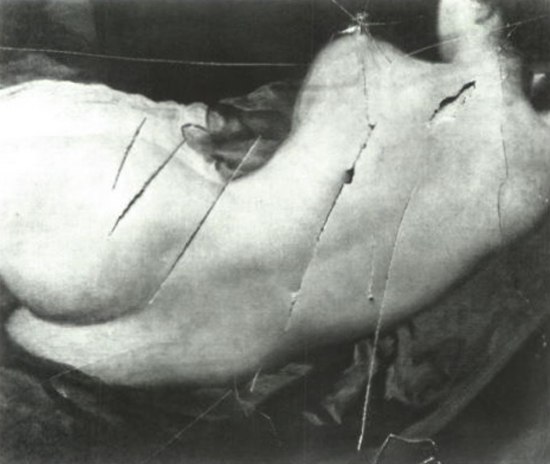

– Rokeby Venus

Diego Velázquez

The citizens of Norbiton: Ideal City are not image breakers, any more than we are book burners. This is not how we have chosen to inscribe ourselves on the World.

But we are learning. That we are cultural accumulators, rather than demolishers, clearly lies at the root of our collective and individual failures. We do not take hold of our adversaries and shake them to the roots of their hair. We do not blow holes where the doors should be. We do not tear down what lies in our way.

This is not going to change—not much ever does—and we are comfortable with that. We will die like the illiterate Krook of Bleak House, surrounded by the mysterious indiscriminate detritus of a culture we were never really part of or party to.

But it is increasingly clear to some of us that if we wish to ensure that the arrangement of cultural goods in the ideal city—that sublimate of our better parts—remain fresh, open, and rational, we might need to add a little tearing, uprooting, defacing, BURNING, and striking out! to our modest civic arsenal.

—fresh, open and rational—

– Rokeby Venus defaced (1914)

Diego Velázquez, and Mary Richardson

![]()

Hunter Sidney takes a further step, however. As with any city, he claims, each life in the Ideal City is tethered and weighted by concealed and controlling images. In unopened albums, in shoeboxes, in attics, there are photographs of the deceased, of the lost, of the loved and hated; mementos of the painful or best-forgotten past; images so potent that they cannot be easily looked on, are almost magical.

He believes that if we could locate those images, root them out, itemise them, study them, and then calmly eviscerate them, we would mentally unanchor or deballast ourselves, float free away from this endlessly iterated present and end up in some other possible, structureless future.

And he is right to the extent that such images—indeed, all images—create the sustained illusion of presence.

—sustained illusion of presence—

– Rokeby Venus detail

Diego Velázquez

![]()

Forest and field are shaped by fire, generation after generation; cities too are periodically opened by conflagration, old timbers swept away. So too breaking images, or disturbing the accretions of objects, prepares the way for new images, new arrangements. Thus the iconoclasms of the sixteenth century in Northern Europe—in England, France, the Netherlands, parts of Germany and Switzerland—were not a salting but a ploughing of total-image-space.

The art of the Northern Netherlands in the seventeenth century, for instance, saw a proliferation of new image types—the still life, the landscape, the domestic interior—growing up in the interstices of the old vanished art of altarpieces, saints and donors.

—landscape exhibit a—

– Het Lam Gots central panel

Jan van Eyck

—landscape exhibit b—

– Landscape with a View of Haarlem

Jacob van Ruisdael

—domestic interior exhibit a—

– Werl Altarpiece, right panel detail

Robert Campin

—domestic interior exhibit b—

– Woman in Blue Reading a Letter

Johannes Vermeer

So effective, at one level, was the iconoclastic programme that little is left of the art of the Northern Netherlands; sharp eyes will have noticed in the above not only a juxtaposition of centuries but of distinct locales, Flemish and Dutch. The seeming fact, however, of the eradication of a tradition and a form of thought through the eradication of its images was nothing of the sort. A sort of generalised memory was retained; present habit was given form by what had preceded it.

This is how personal—and tribal—memory is supposed to work: by generalisation, by mnemonic ritual and myth. The past was much like the present, only with some useful outcomes retained in a general use form, perhaps with some anecdotal flags and markers standing out here and there in the compost of beneficient forgetfulness.

Memory at its most useful, in other words, is never a narrowly particular regurgitation of precise sequential detail. We have no verbatim transcript of the past in our heads. The aesthetic of the lyrical recollection of past moments—as opposed to a discursive chronicle or epic rehearsal—is not an exclusively recent phenomenon, but is one fortified by the advent of general literacy, of printing, and of photography.

Thus while a photograph or diary entry or the recording of a song may grant Proustian access to the texture of a given stratum of time, or download for us a welter of accidental detail, in so doing it materially distorts the burden of the past, beneficial or otherwise.

![]()

Photographs, in particular, still have the power of the miraculous about them. They are images made without human agency, an arrested splatter of actual photons, conjuring real presence.

The Byzantines called such images acheiropoietai, 'made without hands', and they had a particular status as cult images.

—splatter of actual photons—

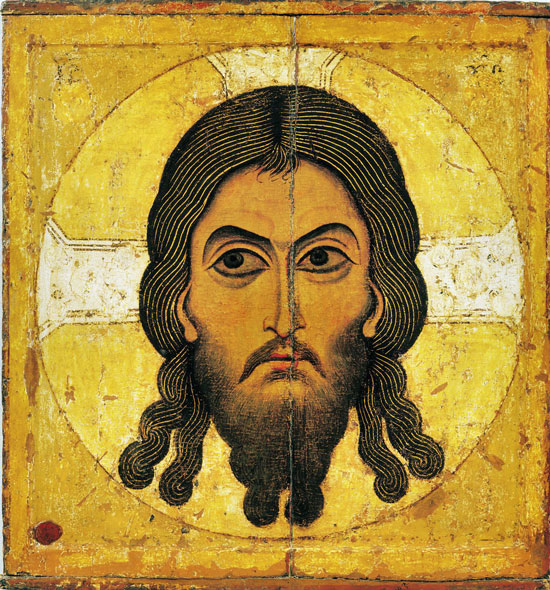

– Christos Acheiropoietos

icon from Novgorod, 12th century

The most celebrated was the Mandylion, the image of the face of Christ created, according to legend, when the saviour mopped his face with a cloth. Similarly the icon of the Madonna and Child known as the Hodegetria (she who shows the way) painted from the life by Saint Luke and credited with apotropaic powers, and in which the Virgin supports the child in her left arm, was believed to have generated the Dexiokratousa('she who holds with her right')—a mirror image of the Hodegetria—achieropoietically, by direct contact.

These images and their offspring were for the most part engulfed in two waves of state-sponsored iconoclasm, between 726 and 787, and between 815 and 843, during which, at various points, arguments were marshalled against and in defence of images. Both iconoclasts and iconodules, however, pointed to the miracle-working (or magic-ridden) power of images. Images were, above all else, effective.

During the Reformation, Calvin genially mocked the rather Byzantine distinctions which Catholics made between the worship, latreia, which was owing to God, the veneration, douleia, owing to saints and angels, and the particular flavour of veneration, proskynesis, which should be paid to images; but Calvin's own position was characterised by analogous careful distinctions, a form of vigilance usually associated with fear of lurking predators. Images, unless carefully handled, were strange and dangerous beasts.

Whether we care to admit it or not, we too are subject to a pre-conscious conviction that a person is in some sense captured in a photographic image, and that we see more of a person in a faded, monochrome, ill-focussed snapshot, than in the best portrait. A photographs is, whatever its limitations, acheiropoietic. We know Lorenzo il Magnifico, or Isabella d'Este, or Federico da Montefeltro, or Sigismondo Malatesta well enough from their portraits; but a photograph, however bad, whether of these luminaries or of their meanest contemporaries, the Failed footsoldiers of their age, would be a miracle of seeing, like having your eye guided to a tear in the fabric of time.

—tear in the fabric of time—

– Boulevard du Temple, Paris (1838)

Daguerreotype, believed to be the earliest photograph showing a living person. It is a view of a busy street, but because the exposure lasted for several minutes the moving traffic left no trace. Only the two men near the bottom left corner, one apparently having his boots polished by the other, stayed in one place long enough to be visible.

Since we have ceased to regard the accurately documented resurrection of the past as a miracle, we might not venerate such an image, or credit it with magical powers. But we would be mesmerised, nonetheless, by its hypervalid presence.

![]()

Byzantine pictorial space is a calculated mysticism: it projects out of the picture plane like a holographic negative, so that approaching the icon brings you within the point at which the orthogonals converge (insofar as they are consistent); and thus inside the pictorial sphere itself, which is, so to speak, the container of presence. You are involved, enchanted, in a miraculous space, the sensorium of God as Newton fancifully put it (without specifically referencing Byzantine icons).

—the sensorium of God—

– Maestà di Santa Trinita

Cimabue

David Freedberg relates how, according to edicts of the Council of 815 (which marked a temporary cooling of iconoclasm) it was permitted to leave in place only those icons which had been set higher up in the sacred space and thus at a greater remove from the congregation, as though it were sufficiently prudent to protect worshippers from accidentally straying within the crackling smog of so many enchanted spheres of possession.

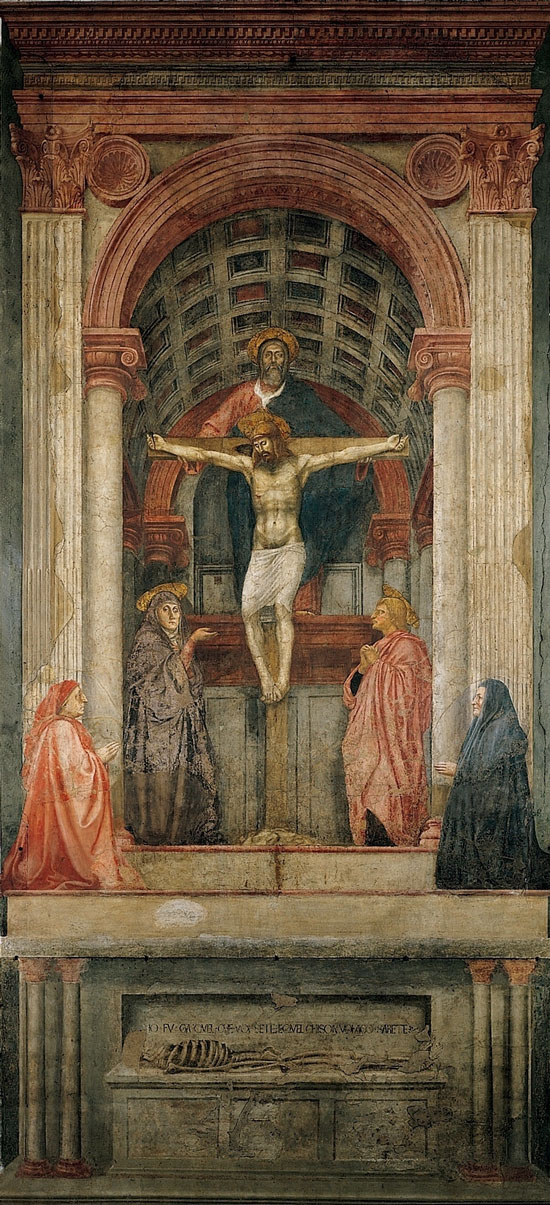

By the quattrocento, the pictorial plane had been inverted, or more properly polarised, and the development and, as it were, perfection of that polarisation is a key element of what we call the Renaissance. The illusion of presence was still strong, and perhaps in some ways stronger, as a result—the work of Masaccio, for instance, was considered technically miraculous by his contemporaries. Pictures were now windows on other, imagined, worlds barely distinguishable from windows on the empirically real world.

—barely distinguishable—

– Holy Trinity

Masaccio

Perhaps therefore it is a little surprising that beyond the persistence of icon-like images, such as the sacra conversazione, the range of narrative subjects remained very narrow. Renaissance art is full of annunciations, adorations, assumptions, dormitions, crucifixions, martyrdoms, last judgements, Jeromes penitent and at study, and so on, each tied to a very tight typological oscillation.

And the representation of those moment is fixed, to a large extent, by tradition. Tradition offers not only psychological continuities—the World remains the World, generation to generation—but also magical transmission. Our rituals, or our modes of representation, work because they are embedded in the structure of the cosmos, not invented out of our heads.

These are more than mere mnemonic aids for the illiterate. These are narrative moments surreptitiously granted iconic status. Narrative sacred art in the quattrocento is an art of the icon, not of the narrative.

![]()

Clarke proposes that we play a parlour game, which he calls Smash that Image!

If you could smash any image, any artwork, which would it be? If you could walk into any gallery and deface a painting, crack the nose of a sculpture, how would you choose?

You will in all likelihood only have one shot, so to speak, so you need to think carefully. Would you be looking to purify, to outrage, or to silence an image?

All are attested sources of motivation. Mary Richardson attacked the Rokesby Venus in the National Gallery partly to summon outrage—she was a suffragette; but partly also because, as she said in an interview in 1951, she did not like the way the male visitors ogled it. Pornography, she intuited, is our nearest functional analogue to transubstantiation.

In 1975 Wilhemus de Rijk, an unemployed teacher, took a bread knife to Rembrandt's Night Watch (a painting with an iconoclastic pedigree, as it were—it had previously been knifed in 1911) because he said the figure of Banning Cocq (whom he identified with the Devil), had been talking to him. Not unreasonably, he wished to silence it. He later killed himself, reversing the logic of his act.

—diabolical Cocq—

– The Nightwatch detail

Rembrandt van Rijn

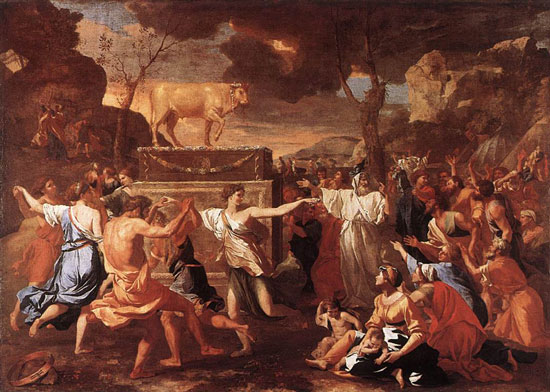

David Freedberg in The Power of Images suggests that attacks on Poussin’s Dance Around the Golden Calf in London were targeting its apparent celebration of idolatry—the knife attack of 1978 dwelt with precision on the calf itself, the more recent spray attack on the twirling line of idolaters. The attacker in these cases and others like them is not, he opines, merely venting rage or madness, whatever that is: he, or she, is interacting with the work, meddling with its power, driving a formal stake through it.

—meddling with its power—

– The Adoration of the Golden Calf

Nicolas Poussin

Returning to Clarke’s question, how would you go about it? Would you use a knife to inscribe your encoded motivation into the canvas? A hammer on some soft marble faun, like a vengeful Thunder God of the North visiting the olive-soft Mediterranean? Or would you go helter-skelter with acid for the sudden urgency of it, the freedom of non-directionality?

And what would you shout as they wrestled you giggling to the ground? You would wish it scripted, I think. Nation’s Favourite Painting my Arse! Michelangelo was an old pope's whore! Bless the Pequod!

The Sistine Chapel—my own answer—would be difficult to bring off. I assume a paintball gun could be loaded with acidballs, and you could, in the few brief seconds allowed you, seek to tattoo your message to humanity over the steroidal nudes and transsexual sibyls, before you were pinned to the ground, wrestling and struggling as the 'Great Artist' himself did, no doubt, in the grip of popes and plutocrats.

![]()

Hunter Sidney makes his comments on images—that we are tethered to them, that we might free ourselves of them—in lugubrious answer to Clarke's parlour game. We are in Solomon’s library: Solomon, Veronica de Viggiani (the achieropoeitic vera icon in person), Clarke, Hunter Sidney, and myself.

The library has become, by accident, an icon-rich space, or iconosphere. We had originally envisaged donating copies (or the originals) of our entire libraries to Solomon’s shelves, either in book form or in digital form, so that the totality of the library would in fact become a number of distinct but overlapping sets. But this was too vast an undertaking and it rapidly faltered.

Instead, a litter of objects had now washed up across the shelves. We started to bring personal effects and deposit them with and alongside the texts, as a sort of ritual of compensation when we provided only digital copies of books. Something for the shelf, we would say, something of actual weight.

My own contributions had included:

- my chess clocks

- my collection of busts (a total of two: one actually an amphora handle, I think, which has a certain anthropomorphic form; and the other a brass door-knocker)

- a Malaysian tapir, scale model

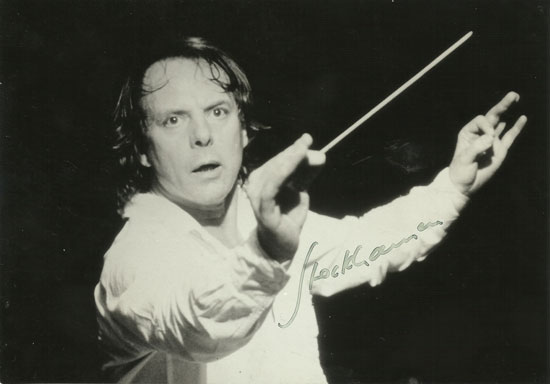

- my signed photograph of Karlheinz Stockhausen, and

- my beetles (again, two: sternocera chrysis chryisidioides and a Lucanid – both from India)

—Stockhausen Acheiropoietos—

And so the library is now configured for images like a Catholic Church. Catholic churches, and also Orthodox churches, are image-rich, as though in cosmic balance with the word-rich liturgy which they host. The liturgy makes no mention of the images, it is essentially a visually spare if wordy ceremony. In any case, this tacit overloading of image space is something we have achieved in what I suppose is our own proto-sacred space, a merged and collective version of our private rooms.

![]()

As Hunter Sidney sits there absorbed by the presence of a photograph in its frame, contemplating, although I do not know it, its destruction, I am granted a sudden intuition—call it a moment of puritanical empathy—and suggest that we ban these images and icons from the library, sweep them off the shelves and into black sacks, and process them around the Norbiton civic boundaries and down to the uncomplicated oblivion of the Villiers Road Municipal Dump.

I call this moment an intuition because it feels not unlike fear. I have realised, from one moment to the next, watching Hunter Sidney's absorption in his image, that like him I have not uprooted the various structural elements which made up that job and life (academic ambition, quattrocento painting, former lover, all that) which I so violently and, I thought, finally quit; rather I have only shifted them here, to this place, in the talismanic form of bric-a-brac, spoglia and whatnot that encrust the shelves. I am the self-same individual, translated, and in this respect am closer now to the brink of universal, or existential failure than at any point hitherto, as though everything I have lived for the last year has been played out in an anteroom to the Zen Enlightenment of true failure.

The force of the intuition subsides almost as quickly as it arrives—perverse proof, perhaps, of its accuracy—and I am pleased to say that no one takes me up on my proposed riot, except Clarke. Clarke says we shouldn’t stop with the library; we should go from house to house—Hunter Sidney’s, mine, his own—clearing out the fungal past, all clinging persistent remnant of the people we used to like to think we were.

He has called my bluff and I let it drop. But I am granted in the process a further morbid insight: that iconoclasm, like all forms of riot, is a contagion; and that Norbiton: Ideal City, being a pure construct built on principles of universal disrespect, has no systemic immunity.

![]()

Iconoclasm can, and occasionally does, proceed in a leisurely manner, by edict. It can be carried out calmly, with bureaucratic neatness, like any municipal work. It can surgically remove the vitals of a given image, rendering it harmless, leaving the remnant corpse intact.

—splatter of actual photons—

– iconoclasm in Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal, Antwerp, August 20th 1566

Frans Hogenberg

But bureaucratic or otherwise the Beeldenstorm (or Image Storm) which fluoresced in the Netherlands in the autumn of 1566 was peculiarly indiscriminate, not only battering the cult images of Christ and the Virgin, but also directing its ire at narrative images, political images (the statue of the Spanish Duke of Alba was dragged down in Antwerp), and secular images. Popular preachers even pointed fingers at images on coins and imprints of books.

It was indiscriminate, but not uncontrolled. It was, according to many accounts, carnivalesque. Image breaking was accompanied by looting, feasting, ritual inversions. In many towns men went about destroying the statues and paintings with ladders and ropes and the tools of their trade, while women methodically looted for food, drink and household goods, and the children (as recorded in Amsterdam) played riotous games of Papists versus Beggars. The impulse was at once centripetal—spitting out the images of external control (the Church, the Spanish)—and centrifugal1, communities stepping out of doors and engaging in common work and celebration.

It is not merely theological energies which are released when the spell of images is broken. The Spanish, who would fight mostly unsuccessfully to retain control of their Netherlandish domains for the next eighty years, were, if they knew it, trying to grasp something ungraspable, something Protean: a society already resequencing its own DNA.

![]()

In 1566, the year of the great Beeldenstorm, Pieter Bruegel painted a John the Baptist Preaching, generally taken to be a representation of one of the rash of illegal Calvinist or Anabaptist or Mennonite field sermons (hagepreken), which preceded the iconoclasm of that year.

—stand awkwardly outside of—

– The Preaching of John the Baptist

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

This is not a painting into whose magic circle you step, an Icon, properly understood. This is a painting which you stand awkwardly outside of, and read like a peasant with your lips moving, your finger tracing the line of the words.

The Baptist is structurally, but not visually, central. He is lost in the crowd, you struggle to pick him out; and while he organises the crowd around him—by the power, you must surmise, of his voice—it is a rag-tag, slouchy, self-determining crowd that he organises, a crowd you would hesitate to join.

The visual centres of the painting are the town in the distance and the vast circular hat in the foreground. The town is a destination perhaps, a City on the Hill, but it is empty of people, the people are here. The hat belongs to an invisible individual, cloaked and concealed, female, or so you deduce from the baby in her arms and her male fortune-telling companion. But this is not an iconic figure, not 'she who shows the way'. The way is barred to you, the back is firmly turned.

Between the Vacant City and the Aegis-Hat, this is a baffling painting. It is troubled, we might surmise, by the fact of presence in painting per se—it is, after all, a representation of image-breakers by one of the great image-makers of his age.

Bruegel’s crowd might not be welcoming, but neither is it a courtly hierarchy, or a procession of angels. We would not need to wash our hands, or wear a special suit, to join its throng. We might slip in and out of it, be part of it and yet not part of it; be present, half-present, absent. But it is your own presence that is revealed to you, a presence that is usually, in the presence of myriad others, lost; and it is revealed to you, unusually, as a function of the flickering half-attention of others, intent as they are on a silent sermon.

Perhaps this is how the iconoclasm of the Ideal City would look: a pretty stone shell, distant, empty and gleaming; and out here, beyond its walls, unmediated by its structure and roles and implied hierarchies, the poor soft mollusc of the citizen body.