Infernal

—convivial journey to the smoking pit—

– Compianto su Cristo Morto

Niccolò dell'Arco

The Geography of Hell is well known. It has its plains and relief and rivers and cities like any other place. And it has its entrances, its gates, its maw. There are roads that lead there which are well marked, and guides (Sibyls, crones, spirits of the departed) to give you directions.

And where there are roads, there is an economy, a possible distribution and exchange. Devils come up and souls pour in, Orpheus descends, Christ harrows, and unquiet ghosts populate the night of the city, its gardens and corners and backstreets and empty houses, with mischief and evil.

But this ebb and flow, this mild friction of cultural exchange, can from time to time accelerate. In the right circumstances—a riot, a carnival, a sack—any city can become a door to Tartarus, can suddenly find that the residents of Hell are holidaying in the streets below, and that the gate is now off its hinges; or conversely, that we have slipped through the gate ourselves en masse and started to take a convivial journey to the smoking pit, on an insane jamboree to locate and retrieve a soul in perdition, to source information from the all-seeing dead, to wring concessions, to make a barter.

As I say, the Geography of Hell is well known. If you are making a descent, there are maps (a little old, some of them), there are guides (you will need to correct for their honesty). You should have no problem.

![]()

How do you sack an Ideal City? It is easier to shake the roots of a building than to shake the roots of an idea. However, in the case of a city the two are not always wholly distinct. The sack of an empirically real city—Rome, for instance, whether ancient (410, sack of Alaric the Goth) or modern (1527, Imperial Forces of Charles V)—is also the sack of an idea: the idea of civilisation, or refinement, or dominion, or hegemony; the idea of a unified entity, an empire, a body. Strike at the bricks of the city, and you strike also at its idea of itself.

Thus, as Gibbon notes of the Landsknechte, present in numbers in 1527, "It was their favourite amusement to insult, or destroy, the consecrated objects of Catholic superstition: they indulged, without pity or remorse, a devout hatred against the clergy of every denomination and degree, who form so considerable a part of the inhabitants of modern Rome; and their fanatic zeal might aspire to subvert the throne of Antichrist, to purify, with blood and fire, the abominations of the spiritual Babylon."

—fanatic—

– Design for a Stained Glass Window for Christoph von Eberstein, with Landesknecht and the Eberstein Arms

Hans Holbein

![]()

Norbiton: Ideal City also has its empirically real roots, reluctant though we sometimes are to acknowledge the fact. Strike at those and you shake the idea. On July 10th, 2010 Madingley Tower went up in flames and the top stories were gutted.

—gutted—

Clarke, whose flat was on the top floor, found himself sleeping in the aftermath on my sofa. And while he was there, taking stock, I suppose, of the situation, he—we—received news that Alfred Cannoner, the artist whose exhibition Clarke had been on the point of curating in the basements of Kingston Hospital1, had suffered a proto-fatal heart attack and was laid up with masks and drips in a ward of the hospital, a daylight analogue of his own Vitruvian Man, located in the Stygian blackness down below in the boiler room.

![]()

We live in what Hunter Sidney sometimes refers to mordantly as fairly modern times, when a city can be conveniently levelled with explosives as it is sacked. However, in times past a sacking army would, once the walls had been breached, concentrate its force on the soft or portable matter of the city. Buildings could be burnt and damaged, and conflagration would sometimes take hold in wooden towns; but a stone city was resistant, recalcitrant. Sacking it was like sucking the meat from a crab.

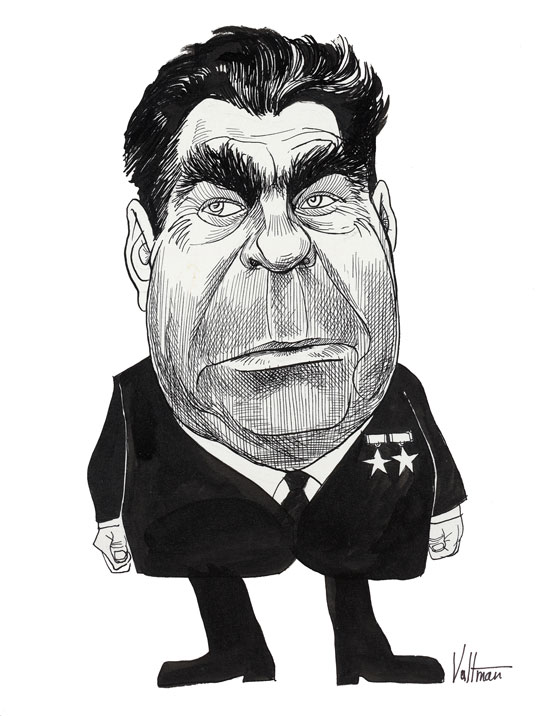

Perhaps there is in fact something to be said for not flattening a city that you attack. The neutron bomb, developed through the 1960s and 70s in the USA and elsewhere (France, notably) and briefly deployed here and there in the late 1970s and 1980s, is an enhanced radiation bomb, where the burst of neutrons released in a fusion reaction is allowed to escape. More neutrons (x10), at a much higher energy rate (14 vs. 1-2) are released in a neutron bomb than in an equivalent thermo-nuclear explosion. Its chief operational deployment was as a battlefield weapon (with artillery shells as one possible vector) designed to kill men in their tanks, but Leonid Brezhnev described it as a Capitalist bomb, because it destroyed people, not property (and, just possibly, because he did not have one).

—capitalist bomb—

– Leonid Brezhnev

By Edmund S. Valtman [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

![]()

Norbiton: Ideal City is sparing of infrastructure. We are all soft parts, so to speak. However, I think this fantasy of the preserved city (or country, or world) is a fallacy. You would not know how to occupy a city that had been stripped of its mechanisms and its relations, nor how to inhabit it. You would drink from the holy vessels, sleep in the tube trains, piss in the stair wells. The city would look like a city but would not be a city.

Francisco de Salazar, present during the first weeks of the 1527 sack of Rome, ticks off the usual horrors—dead horses and pools of blood around the altar in St. Peters, massacre of the innocents in the foundling hospital, graves opened in search of treasure, the Papal Palace used as a stable (not so much atrocious as resourceful) and so on.

But he also notes that "Mass is nowhere said; not a bell or a clock has sounded since the imperialists entered Rome, and indeed no one heeds such things."

The city is transformed for its inhabitants, not only because it is now a place of horror; but also because the usual routines of city life no longer pertain. It is a city denatured. No one goes to work, no one sits in a cafe, there is no set time for anything, there are no reliable sources of anything. In the wake of a sack and perhaps during it also, people are robbed not just of life but of purpose; they lie on sofas, drop nuts down the back of the cushions, muse on their lot.

![]()

While on the ground the sack of Rome would have appeared a chaotic event, to the more general eye, and at a distance of five hundred years, it was clearly the centrepiece of a strongly organised Infernal Geography.

If the Rome of Julius II (1503-1513) or even Leo X (1513-1521) had been located in militant if tarnished glory2 at the heart of the Western Christian World, the Rome of Clement VII (1523-1534) was more precariously situated. The Reformation had taken hold in the North, and in the East, Christendom was threatened by the encirclement of the Devilish Turk.

The armies that gathered in Italy during 1526—on the one side the Imperial Hapsburg forces comprising German Landsknechte and Spanish and Italian troops, and on the other the forces of the League of Cognac under the supine command of Francesco Maria I della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, and including the (much more aggressive and effective) Black Bands of Giovanni de'Medici, recognised as the last of the great Condottiere—tarried and lagged and starved and grew bored as their masters, the Princes of the Christian Republic, discussed universal peace and the Turkish menace.

When, early in 1527, the order was given to the Hapsburg forces under the combined leadership of the perpetually armoured Georg von Frundsberg (1473-1528) and Charles III, Constable de Bourbon (1490-1527) to withdraw (on the basis of a negotiated compromise), their combined troops, starving and unpaid, grouchily rebelled and marched on Rome. Frundsberg, unable to restore order among his beloved Landsknechte, suffered a stroke and returned to Germany to die. The Constable de Bourbon had little effective control over his miscellaneous armies, and was marched by them to Rome where he too died in the assault on the walls.

Thus was the geography laid out, circle within circle within contracting circle, Turks encircling Christians, Hapsburgs encircling the French, and at the centre, the dithering impulsive Clement VII in the Castello Sant’Angelo (built to a circular plan), peering out over his walls (the sack of cities exercises a lurid fascination) at the Barbarians, Goths from Germany and Visigoths from Spain, once again at large in the city of Empire and the Church and going about their repetitive business: raping nuns, massacring innocents, firing towers.

—lurid fascination—

– The Course of Empire: Destruction

Thomas Cole

![]()

Madingley Towers caught fire at around 1645 on Monday 12th July 2010. Clarke wasn’t in at the time, he and his girlfriend Mandy were both at work. But they came home to a gutted flat.

It transpired in the days that followed that the fire had started when a woman on the tenth floor set fire to a dictionary on her balcony. She had become frustrated with a word. She took the dictionary on to her balcony, poured white spirit over it, and set it alight. Clarke couldn’t seem to get this detail out of his head. It was, he noted, as he lay like a philosophically muddled Roman on my couch, very possibly a voodoo assault on himself. Burning a dictionary.

Clarke claimed that he was not bothered by the loss of his material self. He had, however, managed to get some time off in this period owing to what he called his 'situation', and what little of it he did not spend on my sofa watching the New Avengers and eating pistachios, he devoted to the final extermination of what he perceived to be a plague of rats on the allotments.

He had long been setting traps for them on everyone's behalf, as he claimed, and laying down poison, but the traps and the poison had been dispersed over the whole expanse of the allotments and had been, he said, ineffective. He now centred them, all his traps and poison, and all his guile and malice, on his own allotment: it was defended like a Saracen castle with precipices and sink holes and bastions and counterscarps and murder holes and boiling oil and spiky pits.

He caught one rat, and the rest stayed away.

—the rest stayed away—

![]()

To escape from a city in full sack, so to speak, is to make the progress of an Aeneas or Dante through Hell. The whole fabric of the city is immersed in ruin and pain, there is no escape, the city is pinioned on the rack, no one is going anywhere; and yet you walk through inviolate, keeping to the shadows, a spectator, a survivor, nervous, appalled, guilt-ridden.

On the night of 6th May 1527, the first night of the sack, Isabella d’Este was in Rome, staying at the Colonna Palace. The Colonna were allies, more or less, of the Constable de Bourbon against the Pope, and had at the end of 1526 made a proto-sack of the city, driving the Holy Father into the Castello Sant’Angelo. But the Constable de Bourbon was dead and the Landsknechte and Spanish were lawless. That the Palace was safe—and it was, for a night or so anyway—was due to the presence of Isabella.

The Gonzaga of Mantua and the Este of Ferrara (and Isabella was both) had switched sides during the progress of the Imperial Army through Italy, betrayed Giovanni delle Bande Nere, and provided Frundsburg with the artillery he lacked—small mobile field pieces called falconets.

It was a shot from a falconet which killed Giovanni delle Bande Nere in a skirmish: he was wounded in the leg, the leg needed to be amputated, septicaemia set in, and he died. The Gonzaga and the Este, in short, broke the winter stalemate and allowed the Imperial forces a clear run at Rome.

According to her son Ferrante, who was in the city as a lieutenant of Bourbon and who paid her a visit at around eleven in the evening, Isabella gave succour to twelve hundred women and a thousand men in the palace that night. It was impossible, he said, to move without picking your way over their huddled bodies, impossible to stop your ears to their moaning, whimpering, crying, keening.

By 13th May he and some other Gonzaga had assembled boats on the Tiber, and Isabella and her group of refugees were escorted under cover of pouring rain and in the protection of a squad of harquebusiers along labyrinthine streets, through the tortured city, past the exemplary suffering of men women and children, past the great smouldering palazzi, down to the river where, the rain mounting to a full storm, they boarded boats and sailed to Ostia3.

From Ostia Isabella made her way to Civitavecchia, thence overland to Corneto (modern Tarquinia) and from there back by a circuitous route to Mantua. She had escaped with her entire retinue and all the antiquities she had accumulated while at Rome, in what later came to be depicted by her enemies as a mini sack of her own.

![]()

In a painting of 1562 by Pieter Bruegel, the so-called Dulle Griet or Mad Meg, a giant bag lady makes resolute progress, sword in hand, across an insane landscape and towards a gaping hell mouth, as though she were intent on stopping it up, or forcing her way in and leading the reprobate up into the sunshine and air; apparently not realising that diabolical madness is already at large, and that she is the source of it.

—source of it—

– Dulle Griet

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The painting has been variously read, but is most likely an allegory of Madness and Folly. The striding giantess is the allegorical representation of (artificially induced) Madness; her counterpart giant, the figure sitting on the roof with a Ship of Fools on his shoulders, is the allegorical representation of (natural) Madness or Folly.

There is, in other words, no descent. Griet’s motion is all sideways, across the Hell Mouth, and Folly is just sat there. The centre is no centre. There is no down, and there is no up. The horizon is a conflagration of burning cities.

The painting is, whatever else, an emblem of the times. The old world is broken. If, as Hannah Arendt says, the controlling philosophical character in the West was, from the time of Plato and Aristotle down to Renaissance neo-Platonists, wonder—wonder at the world, its constitution, arrangement, proliferation; then from the beginning of the seventeenth century onward, that wonder is displaced by doubt—not merely the Pyrrhonian doubt of a Montaigne, a wholesale scepticism as to the reliability of senses and opinions and an end in itself, but doubt as a systematic motor of enquiry.

It is as though, in the insane progress of Mad Meg, we see the extinguishing, not of reason, not of proportion, but of humanistic wonder.

![]()

"We live in a very disordered time, which we have very little hope of seeing very soon improved, as I fear that it will receive a greater shock, so that the patient will soon be entirely prostrate, being threatened with so many and various illnesses, as the Catholic evil, the Gueux fever, and the Huguenot dysentery, mixed with other vexations... All this we have deserved through our sins.

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)—Geographer, native of Antwerp, friend of Pieter Bruegel."

![]()

Hell is the Great Theatre, the seeing place of suffering. Virgil and the Cumaean Sibyl are not so much guides as usherettes.

I think it is a plausible supposition (one I cannot be bothered to verify) that Bosch and Bruegel derived their hell visions from the imagery of the masked travelling theatrical troops of the middle ages, the morality plays and commedia dell’arte with their tumblers and jugglers, their fire-breathers and bird-masked satires, a broad visual comedy of recombination and transformation.

—tumblers and jugglers—

These were demotic theatrical forms, associated with carnival and holiday, and Bruegel’s carnival scenes and hell scenes and sack or massacre scenes are, if not interchangeable, then easily confused, each overlaying the next: the Dulle Griet bacchantes could be cut and pasted into his Carnival and Lent; his Carnival could be a corner of the procession to Calvary; the procession could be a massacre of the innocents; the massacre of the innocents a detail of the Children’s games.

—cut and pasted—

– The Battle of Carnival and Lent

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

These are densely-packed worlds and under the pressure of crowds carnival spills over into violence. It is as though the ontological states available to any given man or woman, or to any given society—hell, purgatory, paradise, earth (and the twelfth-century Nicolas of Clairvaux adds the paradisus claustralis)—had become compressed, thinned to translucence, paradisical gold to airy thinness beat, such that hell fire luminesces behind it.

Moving from one state to another is a matter of fractions of degrees, a half turn of the head, a momentary relaxation of vigilance, a sag in your energy, a change in the seasons, a glucose sweet, a Martini; slipping about through the fractured structure of the universe in such a way that there is no tracking back, no retracing, no guide will take you back the way you came: there is only repetition, Meg-like occupancy of a self-generating labyrinth of pleasure, of pain, of fear, of regret.

![]()

No one eats their livers in Norbiton. No one pushes rocks or gets bound upon a wheel of fire; no one stands on their head in a lake of fire, or is picked up and thrown about by a screaming wind. We are, by these standards, a happy people.

But we are not immune to more ordinary suffering; while you and your spirit guide would pass through our Stygian deep without noticing us, we are, like you, intermittently cancerous, debilitated, depressed, enfeebled, faltering, unsure, bewildered; we ache, we groan, we creek, we stoop; we despair, and we die.

When, at about two in the morning several days after the fire at Madingley Tower, Clarke received the message that Cannoner had suffered a heart attack, he came and woke me, made me get dressed, and took me over, as I supposed, to see the dying man.

It was a Friday night. I had vaguely imagined, while I was dragging on what clothes lay to hand, that we would go around to the main entrance, announce ourselves as relatives, sit waiting for news with Styrofoam cups of wan tea, amid the groans of drunk hooligans recently emerged from the cracks and fissures of micro-violence that open each week in small towns.

But no. Clarke was my Virgil and knew the back entrances to the hospital. We made no attempt to see Cannoner that night, that was not on Clarke’s mind. He wanted to go and inspect the exhibition he had been curating, Cannoner’s Vitruvian man. Or anyway inspect its ruin. I think he took me with him because he was scared to find the dismembered man remembered, so to speak, banging on the door like the mummy’s revenge.

I hadn’t visited the exhibition space before and I don’t know what I expected to find. A warren of netherworld tunnels, forgotten rooms, storage spaces, skunk-lit and signposted with hand-painted signs; old armchairs and a fridge full of beers, the chunks of the Anatomical Man attached to the wall with hoops of metal, or on spikes for all-round inspection. If it had been me I would have matched the electronic and circuit-board flesh with illustrative diagrams of his bodily systems, a guide to the Arcanum of the Latin Body.

I saw now that the exhibition as realised was almost impossibly modest.

It occupied a single room, a few strides across each way. It was insistently noisy with the hum of the boiler which occupied one corner, and it was over-warm. There was a table running the length of the one free bit of wall, the Vitruvian man strewn over it. The room was lit by two merciless fluorescent strips. Why Clarke had come to see this, I couldn’t say. Perhaps, as I hinted above, he needed to see that it—the exhibition—was really dead. Perhaps he had really wanted to look at Cannoner but had come to his senses at the last moment and brought me down here to view Cannoner’s simulacrum instead.

So there we stood, staring at the ugly incomplete object, just me and just Clarke in the middle of the night standing in front of that appalling piece of junk, that abomination of collage, poorly conceived, poorly assembled. And thus, in a moment of great weariness, the Ideal City, for a fraction of a second, blinked out of existence.