Gastronomical

—salt—

– Banquet with Mince Pie

Willem Claesz. Heda

I once knew a bishop, a noted theologian, who ate only salted toast for breakfast. He was a model of retired asceticism, shuffling around with his mild and distant prelate's smile, his belly lined with small but sustaining quantities of dry toast.

For all I know, my bishop was a subtle purist, consuming his salted toast in a sensory and carnal ecstasy, an ecstasy he misidentified as a mystical experience.

Be that as it may, salted toast is the acme of the gastronomical object: it is at once a fetish of the ingredient and an acquired taste.

The ingredient, in this case, being salt.

—fetish of the ingredient—

![]()

Salt has a magical or alchemical quality.

By itself inedible, a non-food, in subtle combinations it alters the timbre of a given taste, suppressing certain spikes in the chemical signatures of what we eat, allowing others to flourish and opening up a dish for inspection by your palette. An unsalted meal will be a muddled dull lump in the mouth. Thus we say salt brings out a flavour.

It also carries a taste of its own, more or less acrid depending on its purity, which as infants we acquire and as adults we come both to relish and to fear.

—relish and fear—

– The Burning of Sodom

Camille Corot

It is the emblem of all gastronomy, the ingredient par excellence.

![]()

The ingredient is the smallest gastronomical unit known to man.

It is conceptually indivisible. In a culture's gamut of ingredients, its cooks' cupboard, a whole naturalia of plants and animals and minerals is stripped back to its various edible properties, which are then tagged to a location. The ingredient comes from a place. It is Pugliese oil, Galician anchovies, Cretan honey, Maldon sea salt. Jimbalian fudge.

The ingredient is where we locate wholesomeness. It is the ingredient that says to us, well-being, health, purity, pleasure, goodness. Thus we assemble our ingredients in ample space on the kitchen work surface, in their bags and packets or wrapped in paper, or chopped into little dishes, an illusion of taxonomical completeness and order rapidly dispelled in the hot steaming chaos of cooking, in the always imperfect facture of the dish; and then we recycle them, pulling yesterday's dishes from the fridge and reconceptualising them as ingredients to a new dish, a gastronomy of scrag-ends.

And while the gastronomical object assembled from these ingredients is a compound or complex one, it is not therefore opaque. Ingredients are combined, juxtaposed, cross-referenced; but they are not indiscriminately mingled and multiplied. The aim is to achieve a separation, a chromatography of oral sensations. Complexity, as and when it develops, is held in constant tension with transparency.

This transparency is not guaranteed by the purity of the ingredient alone. It is hard won through a set of processes—known collectively as cooking—allied to a keen sense of taste, both of which are not only acquired, but in time hallowed, sanctified.

![]()

Clarke argues that the ingredient finds its natural context, not in the meal, but in the dish. A dish is a bottom-up assembly, a forum for ingredients and processes, which are its two essential constituents. A meal is assembled not from ingredients, nor from dishes, but from plates of food; and it is always located in a broader context of conviviality.

—conviviality—

He makes his observations in the New Devi Tandoori restaurant on Kingston Hill, a convivial spot in which you can eat like a philosopher (as opposed to a theologian).

You ascend to the restaurant chamber by a short stair between the external and internal door. The chamber itself is of modest, you might say quattrocento, proportions. The bar is to the back, there are tables arranged along the walls and through the centre of the space, and it can seat perhaps fifty diners, perhaps fewer. The food is well cooked, fresh, distinctive, hot, and the restaurant is reasonably popular.

There are five of us in our party in the New Devi today: me, Clarke, Hunter Sidney, Solomon and Emmet Lloyd. It is a weekday lunchtime, and we are the only customers.

Restaurants are the bourgeois ideal of a convivial space, but the New Devi is not, properly speaking, a restaurant. What is it? In Italy you can distinguish trattorie, osterie, ristorante; not to mentions bars and all-night rosticerie. Not every kitchen with tables is a restaurant. Also in Norbiton there are cafes, pubs, take-aways. And there are the curry houses.

The distinguishing features of a curry house—as of any truly convivial space—are several: the food, the beer, the over-attentive but somehow not irritating service, the liqueur on the house, the decor, the table furniture including plastic flower; and the music, a few distant ragas like white noise, familiar, comforting, characterless, so that you can, for instance, share a meal in silence if you wish—by no means inconsistent with conviviality, properly understood.

But, unlike the gastronomical experience, these individual features are not analysed out. The convivium is necessarily a continuum.

![]()

Food in the New Devi is a particularly dense and complex object; it is an assault course, a brow-mopping experience, warm bread and cold beer, dripping gravies, acrid chutneys and whole green chillies; it is the sort of food the eating of which obliges you to enter, in your small way, a spectacle of gastronomy.

—spectacle of gastronomy—

– Feast of Acheloüs

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder

The gastronomy of the cinquecento, similarly, worked to a principle of the spectacle of the dish.

The medieval world and the classical world had had their own versions of gastronomic spectacle, but it was the particular fusion of Florentine sophistication with French centralised power, as realised in the marriage of Henry II of France to Catherine de' Medici in 1533, which exploded food and feasting into the myriad-faceted object we know today as la grande cuisine.

Catherine arrived, the legend goes, with chefs and pastry makers in her train, and set about revolutionising the bone-chuckers of the medieval court, introducing in the process such delights as canard a l’orange, carabaccia (onion soup), peas, beans, artichokes; and gastronomic protocols such as the separation of salt and sweet foods, the use of the fork and the division of the meal into courses. She also started fashions for fine table furnishings, silverware, glasses, embroidered napkins.

—use of the fork—

History, needless to say, is at once more brutal and more subtle than myth. French cuisine was already undergoing many of the changes with which its queen was credited, and Catherine's principal contribution, we are told, was to sharpen the contrast between Paris and the rest of France: la grande cuisine was to be a strongly central, non-local food-event, an object of power and control; a cuisine which sucked everything it could into the centre in the form of ingredients, and belched them up again in the form of spectacles of eating: swans stuffed and re-feathered, glazed boars, fountains of wine, showers of sugared petals, all of the visual and mechanical excess which the sweating cooks and engineers of the Renaissance could muster1.

![]()

Consequently, perhaps sympathetically, most cinquecento representations of gastronomical matters separate the formal setting of the meal from the fact of the food itself, and we have on the one hand last suppers and feasts of Herod and weddings at Cana where there is not much eating or drinking going on but where everyone seems to know his or her place, and on the other displays of food disgorged on tables, proto-still lifes, where there is not much eating going on, even though, as in this by Beuckelaer, the Lord God Christ Almighty is getting his feet washed off to the rear (and perhaps wondering if they can just do him a piece of salted toast or something):

—food disgorged—

– Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

Joachim Beuckelaer

![]()

How, in contrast, is the convivium represented?

Jacopo Bellini’s last great painting, known as the Feast of the Gods, was painted around 1514 for the studiolo of Alfonso d’Este, brother of Isabella, under instruction from Mario Equicola, a humanist poet and scholar in the service of Alfonso’s sister Isabella at Mantova.

—convivium—

– The Feast of the Gods

Giovanni Bellini

It represents a moment described in Ovid's Fasti where Priapus (on the right, below), stimulated by the excesses of the feast, lifts the skirts of the nymph Lotis with a view to stealthy rape; but she is awakened by the opportune braying of Silenus’s ass (on the left of the picture, gearing up for a bellow). Priapus is caught in the moment and laughed to shame by his fellow gods.

A quorum of the gods is assembled. In the centre Jupiter is sitting companionably with his eagle. To the left of him, Bacchus, depicted as a child, is drawing wine from a barrel, and Silenus is hugging his donkey, and Mercury is lounging in the foreground with his caduceus; to Jove's right, Pluto has his hand on Persephone’s knee, while Persephone is eating a quince. Beyond them Apollo, hand on lyre, is having a drink, with Ceres sitting next to him. Various lower orders of creation (satyrs, nymphs) are waiting table but also partaking of the feast in a fraternal sort of way.

Personally, as feasts go, I’d want a little less sexual assault, a little less donkey; a bit more food (fruit is barely food), and more variety in the alcohol (perhaps some cocktails, or a pyramid of flaming sambucas). But there is nevertheless an easiness and an exuberance about the disposition of the figures which reflects, or perhaps promotes, a vision of harmony without hierarchy.

As we have seen elsewhere [see Celestial], the gods of the Renaissance could double as aspects of the complex soul and do talismanic duty in banishing, for example, saturnine and melancholic humours. Whether Equicola’s purpose was more than didactic I do not know, but I would be pleased to think that the painting is in some way a depiction of the inner convivium, an assembly of spirits momentarily at ease with each other and the material world of naiads, satyrs, pricks of lusts and snorting asses.

![]()

We are not gods, nor yet masters, and acknowledge the dominion of neither, so the convivium of Bellini’s gods fails for us in the end. I cannot but feel, as I look at it, that I would be the tootling satyr, dancing in profile for a well-modelled Mercury’s peripheral amusement.

Our feasts are more thoroughly demotic. In the New Devi Tandoori we are approaching the fulcrum of the occasion. The waiters have wheeled in our dishes on oiled trolleys as though from the kitchens of another world, they are disposing silver-grilled salvers the length of the table, lighting the devotional candles, softly moving the imperishable flowers in their decorated vases to one side. Some years ago the manager replaced the floral motif plates with plain, square, slightly concave ones; these are now polished and placed in front of us. We murmur our thanks; the waiters in return murmur the names of the glistening dishes as they appear: chana massala, lamb tikka jaalfrezi, vegetable dansak, lamb patia, pilau rice. We start to spoon the familiar exotics on to our plates as the waiters silently withdraw, great mounds of rice and meat stretching in front of us like the feasts T.E. Lawrence describes.

Hunter Sidney is sitting listening to Emmet Lloyd list restaurant meals he has enjoyed, each meal, each restaurant brought to memory by mention of the one preceding it, so that Emmet Lloyd continues to proliferate examples without, seemingly, the power either to generalise his experiences or to stop himself; I am not listening to Emmet Lloyd but watching Hunter Sidney, because he has some chickpeas balanced on a three dimensional wedge of naan, and I find this an oddly interesting object. I am looking at the wedge of naan, a sort of folded up cone, and I am wondering about dimension in food: whether the fact of a three-dimensional infolded structure being placed in the mouth is different from simpler, say flatter shapes being placed in the mouth.

I am sure it is, but could you therefore look at a plate of food and somehow read the taste of it in the shape? The contours and blocks and volumes of food on the plate (heaped, distributed, separated, smeared, flattened, puffed) might be—perhaps are, by obsessive chefs—indexed to the shape of the mouthfuls you are expected to knock off them, like a sculptor.

Hunter Sidney eats the mouthful of naan and chickpea and allows Emmet Lloyd to complete his catalogue; and then Hunter Sidney tells us about the news he has had of the recurrence of his cancer.

From the expression on our faces the five of us might suddenly be adrift in a lifeboat, having just cast lots to see who eats whom.

![]()

Ours is a literate kitchen culture. We not only reflect on what we do in kitchens; we write it down. And this writing down is more than a record of what we generally do, a memory system, a periplus of salty promontories and bitter wrecks—it will gradually determine how we do things in future. It will be an analytical tool.

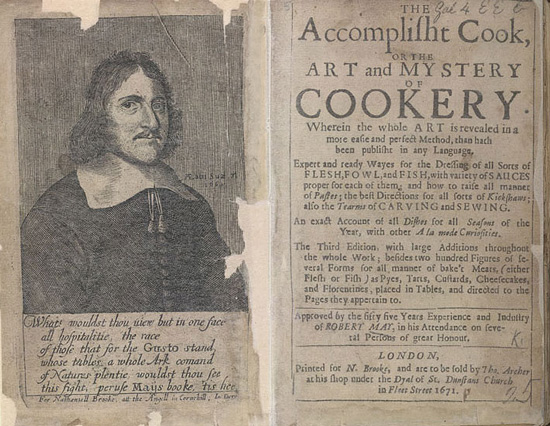

—salty promontories and bitter wrecks—

– The Accomplisht Cook

Robert May

And not only analytical of processes. Ingredients become ingredients in virtue of our descriptions of them. Pepper cracks, oil drizzles, cream dollops; duck is fatty, rice is fluffy, potatoes floury. Oil, as I have remarked, is Pugliese, Cream Devonshire, Salmon Scottish.

In the conversation in the New Devi which follows Hunter Sidney's announcement, Clarke recalls2 that his friend in Rome, Ray Bartley, devised his own system of flow-chart recipes, in an attempt not only to record better his kitchen practice, but to streamline it. But he found over time that he began to regard his cooking not as a sequential practice, a following of steps, but as a recursive one, a continual return to a hob or an oven to monitor temperature, adjust seasoning. Cooking became a sort of oscillation around an object, rather than a march to the table; which induced or perhaps merely exposed a routine fretfulness that could only be dissipated with an array of thermometers giving up real-time data which he could then feedback into his dish-system.

Whether in time this led to a new cooking in the Bartley kitchen is unknown. Also unknown is whether the recipes were to be accompanied by photographs. Because the Ideal Object of gastronomy is not a recipe, in the end, but a close-up of the inviolate dish.

Perhaps Catherine de’Medici’s spectacles of la grande cuisine were an inevitable consequence of the invention of printing a century earlier, and it awaited only the development of colour plates for gastronomy to be sucked, in its entirely, into The Book.

This is how we now represent food to ourselves: the extreme close-up, the adjectival welter. By contrast, we have no active tradition to represent people eating. When we try, we are conspicuously uneasy. Because we know that tables in restaurants are islands on which diners are beached, family dinners are a cavern of silence, and the dinner party is a Herod's feast of grotesque punishment.

—a Herod's feast—

The Bartley flow-chart, in this context, is an emblem of sanity, a demystification. Learn to cook, the lesson goes, so that you can stay in the kitchen, and eat alone, ruminatively, when customer and guest and family have trailed back from Calvary.

![]()

Michel Jeanneret notes3 that in the years of the High Renaissance (roughly 1500-1527) the Last Supper fell from fashion as a subject for painters.

Its formal qualities and problems had appealed to the Florentines of the quattrocento, who painted it—or had it painted—again and again, on refectory walls of one monastery or another, as for instance here by Andrea del Castagno, with those typically gristly quattrocento scorci, or tricky foreshortenings (of heads, mostly, in this case), brilliantly handled within a shallow space adapted to the horizontal composition.

—gristly scorci—

– Last Supper

Andrea del Castagno

The last supper is not so much a last meal as a last symposium—a dining together at a point of crisis where what needs to be said is framed in ritual rather than in conversation. You can imagine Christ, like Feisal, or Hunter Sidney, making believe with his hands on the bread and lamb of the Passover, until the moment comes when the ritual must take form.

The ritual in our case is a flaming sambuca. At the New Devi they never fail to offer you a liqueur on the house as you pay your bill, and we never fail to accept. We always have a sambuca which they bring to the table flaming, a couple of coffee beans toasting there. We watch the mild candescence belch like swamp gas over the clear liquid. Then we lean forward and carefully puff it out, and drink in silence, reverential or embarrassed as the case may be.

Perhaps, where the quattrocento liked to think of Christ and his apostles at the Last Supper as neo-Platonic philosophers punctuating their dialogues with a few grapes, the cinquecento understood that we eat to forget.

In 1573, Paolo Veronese stood accused before the Tribunal of the Inquisition in Venice over an enormous Last Supper he had painted for the refectory of San Giovanni e Paolo, now hanging at the Accademia in Venice and known as the Feast at the House of Levi.

—Paolo Veronese stood accused—

– Feast in the House of Levi

Paolo Veronese

Veronese was summoned to account for the variety of irreverent figures in his painting—the serving men, the animals, the mercenaries. A transcript of part of the exchange follows.

Q. In this Supper which you painted for San Giovanni e Paolo, what signifies the figure of him whose nose is bleeding?

A. He is a servant who has a nose-bleed from some accident.

Q. What signify those armed men dressed in the fashion of Germany, with halberds in their hands?

A. It is necessary here that I should say a score of words.

Q. Say them.

A.We painters use the same license as poets and madmen, and I represented those halberdiers, the one drinking, the other eating at the foot of the stairs, but both ready to do their duty, because it seemed to me suitable and possible that the master of the house, who as I have been told was rich and magnificent, would have such servants.

Q. And the one who is dressed as a jester with a parrot on his wrist, why did you put him into the picture?

A. He is there as an ornament.

—ornament—

– Feast in the House of Levi, detail

Paolo Veronese

Veronese was let off with various provisos which he roundly ignored—his toothpick solution was to change the name of the painting, not to paint out the innumerable offending figures—but in the matter of defiant insolence, he had form. He had in fact turned the Last-Supper-at-Gomorrah into something of a genre piece. There is, for example, the enormous Wedding at Cana now hanging in the Louvre, which he might have asked to be taken into consideration.

Christ sits, whether in the House of Levi or at Cana, and mildly endures the vivifying chaos. Like Wotan in Valhalla, he is in passive-agressive pursuit of some elusive, probably inexistent, greater order; rehearsing in the form of this convivial moment suppers still to come where the feasting will be stripped back to a decorous and ritual contemplation of salvation.

Only, as Veronese very well knows, this is the last supper, and there is no salvation, just the salt toast of imminent and bewildering death, enjoyed in the company of ornamental jesters.