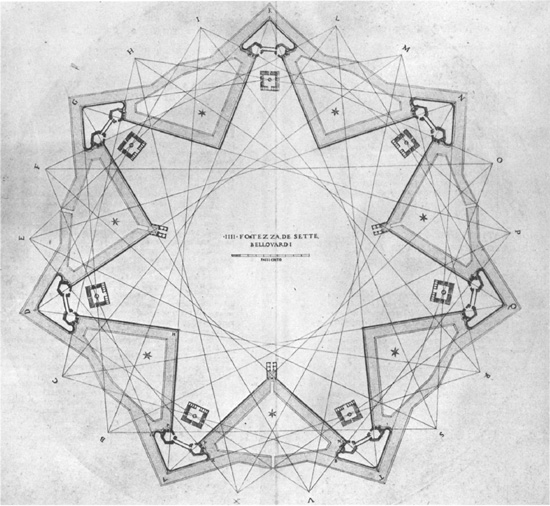

Geometrical

—city that repels—

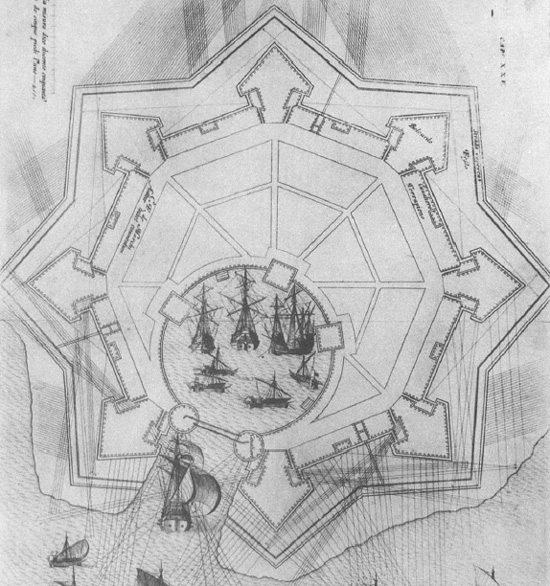

– Model of a design for a fortified port on the Brandenburg Sea,

Bayreuth Historisches Museum

The Ideal City as imagined by the quattrocento Renaissance is not a city that defends itself, but its geometric regularity, while originally merely intended to open out and rationally sub-divide its civic space, can also be tuned to a diamond hardness. The Ideal City can translate itself into the city that repels.

In contrast, Norbiton: Ideal City, while laid out according to a rational and (potentially) intelligible geometrical scheme, is a conspicuously defenceless civic entity. It has and can have no curtain wall, no drills, no militia; it does not busy itself with ballistics or breaches. It will fall—at any rate melt away—at the merest breath or rumour of assault.

But then, neither is Norbiton: Ideal City subject to a regular Euclidean geometry. The Failed Life has its Geometry for sure, but the space upon which it is written is curved, folded, n-dimensional, strange; and to describe any one point—this location, this moment, this predicament—even incorrectly will require a formidable headful of co-ordinates.

Paradoxically however, Norbiton is itself an outgrowth of strong points, bastions, ravelins, demi-lunettes, and the whole apparatus of tortoise vigilance. Each of its citizens is bristling like a Swiss Guard with defensive attributes. If, as I suspect, the best foundation for a proper defence against the World and all that it can do lies in studied equanimity, then that equanimity will in turn only be delivered by a properly prepared map, or plan, or approximative geometry of Norbiton’s various invisible perimeters and redoubts, and the lines of communication that connect them.

—properly prepared—

![]()

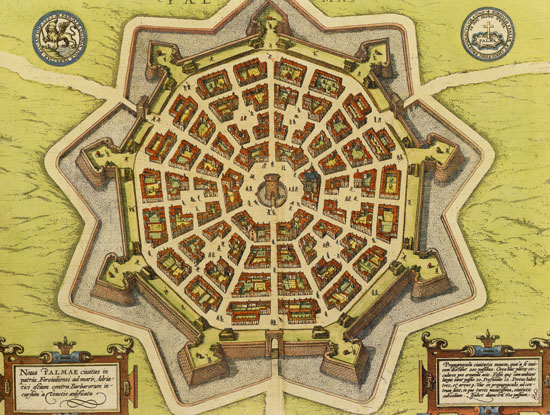

One of the only towns to be constructed according to the rational principles laid down by Alberti in the 1450s (in de re aedificatoria) and imaginatively developed by, for example, Antonio Averlino (known as Filarete) in his designs for the ideal city of Sforzinda, was Palmanova, a fortress town on the margins of the Venetian Republic in the 1590s.

—lone hieroglyph—

In the same way that Ficino, following Pythagorean tradition, understood certain musical intervals to chime with the harmonic structure of the universe, so the early Renaissance understood that the geometry of towns could be made to click into place with the geometry of the created universe. The rational designs were embedded in a deeper, fundamentally irrational search for order in patterns. Thus Palmanova, from the air, looks like nothing so much as a crop circle, a lone hieroglyph, a letter to the gods.

Conversely from the ground, with its low profile and raised earthworks, it can hardly be seen at all.

—hardly be seen—

![]()

"The perfect fortification belt envisioned by the sixteenth century military architect ... was a regular polygon with blunt, evenly spaced bastions and predetermined curtain lengths, which could be surrounded with an impenetrable wall of defensive fire created by tightly interlacing firelanes."

Horst de la Croix, 'Military Architecture and the Radial City Plan in Sixteenth Century Italy', The Art Bulletin, Dec. 1960

![]()

Between Alberti and Palmanova the Renaissance lost interest in Ideal Town Planning, and civil and military engineering began to disentangle themselves from the more humanistically-oriented pursuit of architecture. However, the ideal form of Sforzinda and its cognates was hijacked by military engineers anxious to combat certain advances in artillery and ballistics which had rendered the medieval fortress obsolete, almost overnight. In particular it was supposed that correct geometry would thwart the iron cannonball.

The iron cannonball was first used extensively on the Italian Peninsula in 1494 by the army of Charles VIII of France. Its predecessor, the stone ball or the stone ball reinforced with iron bands, would mostly crumble on impact with stone walls, and a thick, well-made stone wall was therefore impregnable. Moreover, the sort of ordnance capable of throwing a stone ball sufficiently far and fast to dent even poor masonry was too cumbersome to allow very mobile campaigning. The medieval world was one of corpulent defence.

Charles VIII with his iron artillery cheerfully smashed his way through the Italian peninsula in a matter of weeks. Garrisons learnt to capitulate at the mere rumour of his approach. No wall could survive the assault for more than a few hours—thickening them would only delay the inevitable, and not by much. Charles could allow himself to stand, unsullied, unsweated, in the gardens of Poggio Reale and breathe the perfumed air in enlightened peace.

Slowly the cinquecento came to grips with the problem. The key, as Alberti had also realised, lay in the geometry. If a wall could not stand an assault, then it became necessary to work on the assumption that it would fall, and place defensive bastions sufficiently close together than any attempt to enter at a breach would be destroyed by enfilading fire. The profile of both walls and bastions could also be lowered to increase the effectiveness of artillery fire (a flatter trajectory would carry more before it), and sunk behind earthworks, counterscarps. Enemy gunners would be able to target only a useless fraction of the wall depth.

The walls between the bastions, clearly, had to be straight, so that their whole length could be protected by both bastions. The best shape for a bastion was triangular, so that flanking bastions could protect their whole front (round bastions created a dead space which could be sapped or assaulted).

Thus as the circumference expanded, and the distance between the bastions remained constant (governed by effective artillery range), the shape of the ideal fortress or fortified town, always regular, would approach, but never attain, the perfection of the circle (perfect, argued Alberti, if nothing else because the circle enclosed the greatest area for a given circumference).

A city, or a fortress, could still be successfully besieged. But the besieger would know he was in a fight, not only with stone fortification and counter-battery fire, but with the impossible weightlessness of Ideal Geometry itself.

—impossible weightlessness—

– Design for a Fortress,

Galasso Alghisi

![]()

The logic of Italian geometry was indeed formidable, and by the middle of the century Italian engineers had not only caught up with but surpassed their Northern counterparts.

The curtain wall was so skilfully protected by its flanking bastions that the bastions themselves necessarily became the focus of any attack. The defensive priority was now, therefore, to use the advantage of internal lines of communication (maximised by the radial street plans so beloved of the designers of Ideal Cities) to swing defensive resource rapidly to whichever bastion most needed it. Those radial street plans of the Ideal Cities of the quattrocento now took a clockwise click and no longer linked the central square and the civic buildings with the gates, but with the bastions.

In every treatise on fortification from the second half of the cinquecento, the convenience of the inhabitants of the city is subordinated to the demands of defence.

—clockwise click—

– Design for a Port Fortress,

Francesco de Marchi

![]()

In the Atomic Age, the modern city—including Norbiton, that most modern of all cities—became largely defenceless against actual attack. As with the defensive reappraisal consequent on the iron cannonball, so with the advent of atomic weapons planners were forced to work to a different paradigm, abandoning Euclidean geometry in favour of models of distributed networks.

Broadly, the key to defence was now one of target dispersal and redundancy. Important facilities were duplicated, moved out of population centres, and buried under mock bungalows; plans for mass evacuation along radial highways were drawn up, populations were tutored in the drills of civil defence, in part against the blast patterns of nuclear strikes, and in part against the invisible floating malaise of radioactive fallout.

—mock bungalows—

– Kelvedon Hatch Nuclear Bunker, entrance,

Photo: Genesisman26 at English Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

With time, however, and the multiplication in both power and number of nuclear warheads, the priority shifted: what really concerned the defence planners of the post war was not the survival of civilian populations but the integrity of the command and control structures, the proper functioning of missile silos and counterstrike capability. And so the ideal 20th century fortress becomes an encrypted map of dispersed military resource, resource tending not to the Albertian perfection of the circle but to the hyper-modern perfection of the dimensionless point.

Except where it proliferated underground. While silos poke the merest tip of a nose into the air, and command and control centres only venture the odd aerial above the surface, beneath, it is different—from miniture warrens of back-garden and public fallout shelters, to subterranean cathedrals glorying in an international gothic of ducts, coils, tunnels, and bunkers; cavernous spaces dripping or piled with Bakelite-knobbed and multi-dialled engineering, so many stalactites and stalagmites, so much ornamental encrustation, bewildering self-generative tech-grottos served by a shaven-headed, pink-eyed and uniformed priestly caste—the architecture of what Clarke is pleased to call the whole psycho-military mental object.

—tech grotto—

– Kelvedon Hatch Nuclear Bunker, interior,

Photo: Scott Wylie from UK (Nuclear Bunker) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

And so, by extension, the Ideal City reaches its greatest perfection (or at any rate the greatest perfection of one of its facets) in the erased surface, the vanished apparatus of state, no one left up here on the surface but us, sitting in the middle of an endless blasted plain in the oasis city, marked by its gardens and running water, its tea and abstinence, its contemplative resignation. City of anchorites, visionaries, living out the Failed Life, awaiting, always tending towards, but never attaining, the point of vaporisation.

![]()

To the citizens of the Ideal City all of this is as irrelevant as the shadows which pass over the face of the earth. Nations, we know, are insane, and we neither have nor demand protection against them.

We observe, however, that we too, through species memory, habits of seclusion, or reasoned pragmatism, remain in a state of vigilance, of defensive readiness.

Clarke and our newest citizen, Veronica de Viggiani, are sitting at lunchtime in the Albert, the pub which, as I note elsewhere, guards the borders of Norbiton against the encroaching blank arboreal wildness of Richmond Park.

We are discussing fortification. More precisely, I am discussing fortification.

I point out that Norbiton is, from a certain perspective, already a chain of forts, a sort of Hanseatic league of the paranoid, stretching from the troglodyte lock-ups of Cannoner, to Old Sol’s hedgehog library; blind Nestor in his tower, Clarke cracking cans on his Isolarium and watching as the class war ebbs and flows across the broad floodplain of the Hogsmill River, or skulking in the unmapped subterranean chambers and dungeons of Kingston Hospital; Hunter Sidney in the top room of his dummy house, the empty rooms and closed doors and covered furniture so many traps and lures and spiked-pits imperilling the ascent; and Mrs Isobel Easter, privileged and inaccessible Erda in her lair.

Veronica de Viggiani not unnaturally asks, what is it that you are defending yourselves—and Norbiton—against? And, while my answer elaborates an analogy of Hannah Arendt, who compares the world to a table at which its participants sit, at one and the same time linked to and held separate from one another, (and I indicate as though to a simpleton the round wobble-legged table over which our beer has been slopping) what I am thinking is, I don't remember.

![]()

The Ideal City as depicted by artists in the quattrocento was an open city which extended itself in the infinite homogenous space of linear perspective.

There were Medieval precedents for representing the Ideal City—the City of God, say, or Jerusalem—as open. City gates were typically painted as emblems of porosity, nothing more than civic conveniences, guiding, perhaps lightly accentuating, the spiritual to-and-fro of citizens.

—spiritual to-and-fro—

– The Temptation of Christ

Duccio di Buoninsegna

In the empirically real world of the Italian trecento gates were in fact formidable barriers to entry, with an extensive apparatus of defensive supplements (barbicans, moats), fiscal filters (gates were typically the first element of city walls to be built, a testament to their economic rather than their defensive function, and had a total staff sometimes in excess of one hundred, including guards, inspectors of goods and cashiers), and sculptural or painted apotropaia (Virgins with child, Saint George, etc.). They were, in other words, boundaries that had become spaces in their own right, which had to be dwelt in, endured, escaped from.

And while the open gate represented by artists was a synecdoche for the pleasant welcoming openness of the city as a whole (and still now, being able to leave your front door unlocked stands as an emblem of an ordered society), in reality the gates of medieval cities gave access to an unplanned and uncontainable confusion of streets and buildings. Where free movement was concerned, this was a turgid, if not wholly unorganised, space.

In the city as imagined by the quattrocento Renaissance, the gates are still open and welcoming, but the internal organisation of the city is now additionally uncoiled, relaxed; architecture is encouraged to disport in infinite, but not infinitely jumbled, space; the visiting eye can move through colonnades and open doors, up stairways, look over balconies and out into the well-ordered hinterland beyond (no disgruntled pitchfork-toting contado here).

—well-ordered hinterland—

– The Visitation

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Capella Tornabuoni, Santa Maria Novella

Unlike those Medieval labyrinths in which you would become mired or at best lost in the crowd, or for that matter the crystalline geometrical hardness of a Palmanova which you were not invited to enter so much as bounce off, the imagined space of the quattrocento city was one you could ghost through, like a neutrino, without alerting anyone to your presence, your trajectory, your destination.

—ghost through—

– The Presentation of the Virgin

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Capella Tornabuoni, Santa Maria Novella

![]()

I have, on this particular morning—before meeting Veronica de Viggiani and Clarke in the Albert—been sitting with the woman I call Mrs Isobel Easter, in the room I think of as her grotto. This house is not a fortress, but is nevertheless hard to access. She is showing me again the Etruscan lamp which Hunter Sidney stole for her twenty years ago in Rome, from the museum of the Villa Giulia. I now know the story of that escapade, variously from Mrs Isobel Easter and Hunter Sidney. Mrs Isobel Easter wants me to see to it that the lamp is returned to the museum of the Villa Giulia, and I have it in my pocket as we sit in the Albert.

—I have it in my pocket—

– Sketch of an Etruscan Lamp of the Villa Giulia,

Anna Keen

Veronica de Viggiani, who is keen to reconcile Hunter Sidney with Mrs Isobel Easter before he dies, interprets the emergence of this story from both sides as a softening of their mutual defensive system, and the lamp as a counter to be deployed. She is eager to take advantage somehow, although she does not have a clear plan. Their common sadness, she says, is a tension that should be resolved.

I disagree. Fortresses, I argue, perform their function in many ways, both actual and symbolical. They persist in time, but are only occasionally called upon to do the business of resisting attack, sometimes in circumstances which could never have been conceived at their building.

And so perhaps, to put it bluntly, Hunter Sidney needs all the benefit of his historic fortifications as he approaches his hour of death. We do not know, and should not meddle. If we spring her on him, force the reunion, he might be thrown into confusion; he might, one minute, be looking out over the plain at the ant-like and harmless preparations of his adversary, and then the next find his wall has been sapped, the enemy are behind him, within the walls, furiously rubbing up malignant genii from lamps.

We should leave him to spin out the logic of his own geometrical scheme, however sad that might be.

Veronica de Viggiani just shakes her head.

![]()

Clarke accuses me of constructing a parable, of sharpening up the historical drift in the interests of my metaphor.

Elaborating, he says there is no necessary or logical progression from Ideal City to Ideal Fortress: there is only a general historical growth in mathematical competence, and a concomitant reapplication of relevant ideas. There is no necessity at work, he repeats, only pragmatism.

I counter by fully accepting that there is a pragmatism at work in the implementation of ideal designs. And I give him, as my conciliatory for-instance, Palmanova itself. Palmanova was an exercise, not or not only in rational or geometrical logic, but in pragmatic adaptation.

Take the orientation of the radial streets. According to the logic of the fortress, these should supply not the gates but the bastions. In Palmanova there is no consistency in destination—some run to gates, others to bastions. Then, there is an incongruity between the form of the outworks—a nine-sided polygon—and the central square—a hexagon1. There is no rational principle at work here, only a sort of base mimicry.

—base mimicry—

– Plan of Palmanova, c.1600,

Civitates Orbis Terrarum, Georg Braun

And finally, it is worth remembering that Palmanova was a failure. It failed to draw inhabitants (its outworks still more or less define the extent of the city). By the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Venetians were already commuting prison sentences and exiling convicts to Palmanova.

There is a pragmatism in application, then. But that does not undermine the paradox I have outlined: that openness, the logic of a harmonious geometry, is an invitation to tyranny as much as to the free converse of citizens.

Clarke doesn’t bother to counter directly anything I say (perhaps because I appear to be agreeing with him). But as he stands up to get in a round, he points out, reasonably enough, that Palmanova is not a city that defends itself; it is a fortress city that defends a plain and the domain of a distant tyranny, Venice, a power now sunk to a mere curiosity. Power, tyranny, come and go, and will wash through your city regardless of its formal properties.

![]()

When, later, and contrary to the position I have maintained against Veronica de Viggiani, I give Hunter Sidney the lamp (and he in return gives me the drawing of the lamp that Isobel had prepared for him), he talks for a moment about geometry.

Or rather, he talks about objects—the lamp, in this case, and the drawing—funnelling down towards each other. As he nears death, he muses, he feels that his entire life is within touching distance, objects and people spiralling towards one another, whether in fact or in memory (and he admits to not being very clear, sometimes, which is which).

Life, he says, is collapsing in on itself. But now that he knows that he is dying, his acceleration towards oblivion seems to have crossed some critical threshold of turbulence, and the rattling shivering spacecraft of his body has suddenly sailed out into smooth flight, and all is quiet around him, and he is passing through a more saturated, less reflective version of space-time; as though the gravitational sheer were such that light, here, has been compressed, grown liquid, material; everything he looks at seems slowed in an amber distillate of light, a form of chemical thought.

In geometrical terms, Hunter Sidney is describing life in a funnel.

A funnel is not so far as I can see a defensive geometry. It is merely descriptive of a sort of underlying (non-Euclidean) shape of life. It implies an acceleration, a rotation; it is associated with critical deformations in the fabric of space-time, such as black holes, the impending non-existence of Hunter Sidney, and the empirically real city.

![]()

A planned space—an Ideal City, say—will tend to stall the energy of those who are asked to use it. The radiant cities beautiful of the imagination become sink estates.

The Medieval city, by contrast, largely owed its eccentricities to the multi-centric nature of its social space, the clutter of its constituent and overlapping social objects: the church, the monastic and lay orders, trade and craft guilds and confraternities, the money of merchants, the patterns and flow of international trade, and the desperate energy of the urban, and the continual influx of the rural, poor. Everything funnelled in at the gates, accelerated hilariously, often fatally, all those souls crammed in, jostling towards a higgledy death.

As it happens, this confusion was a guarantor of the liberty of the citizen. A labyrinth is harder to penetrate, to subdue. It is a source of lawlessness, but also a place of freedom. And although these labyrinths provided only a rough and ready liberty for the inhabitants, and a liberty at the expense of what we would recognise as civil order, nevertheless the reality of the Medieval city permitted the growth of a more fecund order, protected from the feudal tyrannies of princes or bishops.

The Ideal City of the Renaissance, by contrast, was unified, in fact or imagination, by the growth of tyrannising oligarchies; communal government and guild republicanism were vanished dreams in fifteenth century Italy, where the powerful men, families, and merchant oligarchs—Montefeltro, Malatesta, Sforza, Medici—had, taken all in all, established a largely unchecked tyrannical rule.

It is no longer the louring castle that speaks of tyranny, but the sunny boulevard. Only a tyrant of the thunderous power of a Montefeltro, to take an instance, could generate a vision of Ideal City, emptied of citizens, as chilling (so the argument concludes) as this:

—chilling—

Perhaps in our end—the end of Hunter Sidney, the end of Norbiton—lies our salvation. Objects break free of their coordinate anchors and flow free in a whirlwind of destruction. We will be, at our end, like Dorothy spirited to Oz, the whole fabric of our world dizzyingly present in the strange final geometries which will there pertain.