notes to the Ideal City: pt iii

...made no hypothesis about what he was seeing...

Which is not to say that his observations did not in some sense conform to his prior beliefs regarding microstructure and sense perception. He was, after Descartes, a mechanist, who believed that properties of substances could be traced to the shape of their smallest parts. His entire microscopy could therefore be said to spring from the hypothesis that the characteristics of being might be seen through a magnifying lens. Lisa Jardine relates, for example, how his discovery of protozoa in water (his animalcules) was a by-product of his researches into the pungency of pepper.

![]()

...testify to the artist’s microscopical eye...

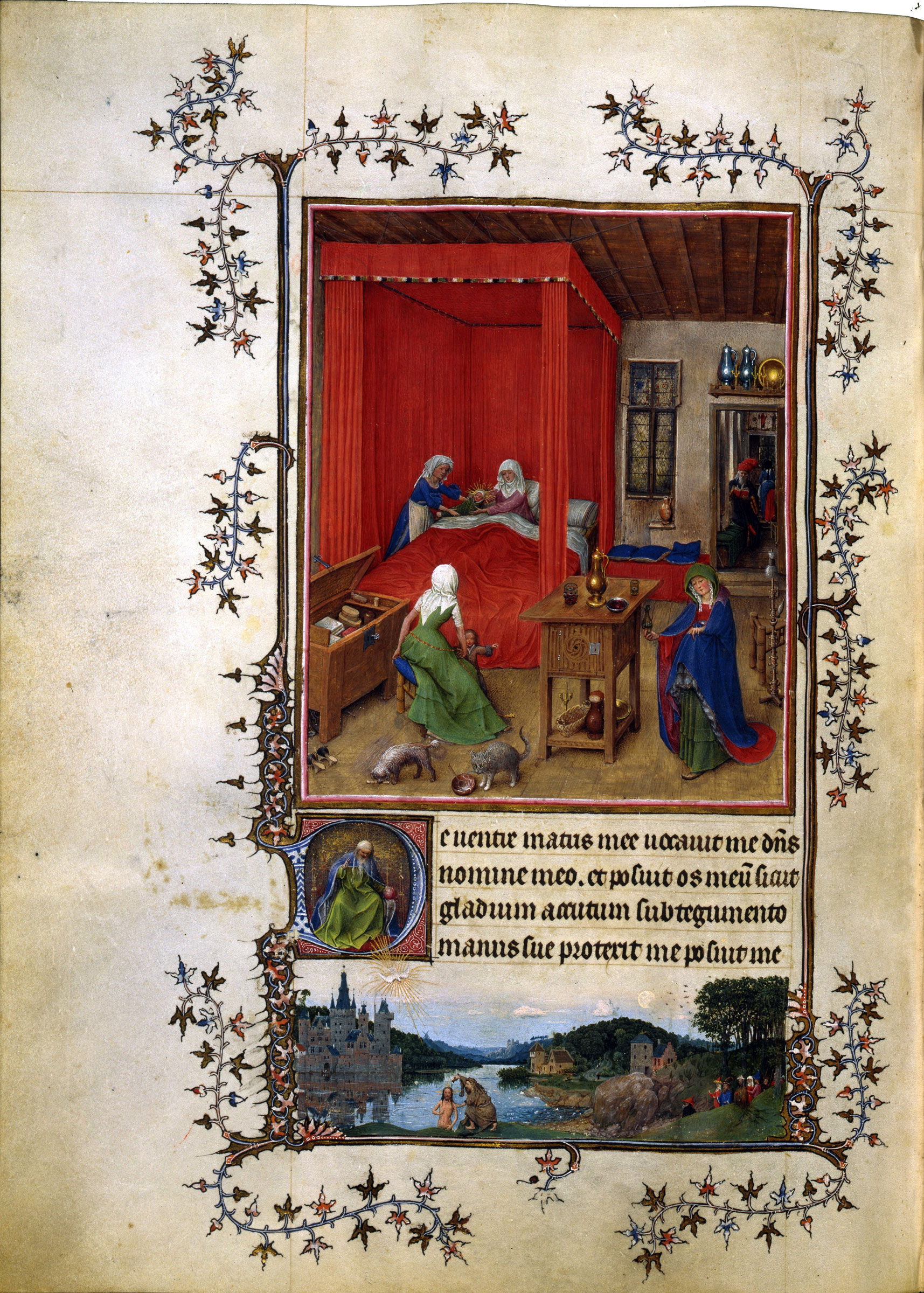

Van Eyck was an illuminator by training. It seems that his is Hand G in the Milan-Turin book of hours.

—Hand G—

– Milan-Turin Book of Hours

It is hard to believe that he did not do all of his painting with his eyes an inch from the panel, swimming behind pebble lenses. That is certainly how I prefer to look at them.

![]()

...once a touchstone of truth...

This is, strictly speaking, an unjustified assertion.

As Paul Feyerabend notes in Against Method, "[t]he ‘illusions of direct vision’, whose role in scientific research is slowly being rediscovered, were well known to mediaeval writers on optics, who treated them in special chapters of their textbooks." (p.86-87 note 17)

Feyerabend mentions this in an aside on the work of physicist S. Tolansky, whose routine microscopical inspection of crystals and metals were distracted, on his own account, by "one optical illusion after another".

It is fair to say that I paint with a broad and sloppy brush.

![]()

...did not think it appropriate to invite.

No labyrinth walk is complete without its monster.

Kelley—doubtless away with his dogs somewhere—is no monster, strictly speaking, but he stands in for us today as our Anubis-Minotaur, displaced by the absence of a properly navigable underworld in Norbiton to mourn and bellow (not literally) around the streets, harrow this upper Hell, set challenges, pitfalls, obstacles, locks, snares, decoys for the soul of Hunter Sidney, for us, for himself quite possibly.

To repeat, there is nothing monstrous about Kelley. He is more a black box of intent, a bit of a mystery, a necessary mental smutch on our smooth pale day. What did he ever know, or intuit, about Hunter Sidney and his wife? Do the recent dead need to appease the intricate souls of the living if they are to make progress away from the world? Or is it the inverse?

—inverse—

– Theseus Slaying the Minotaur,

Cima da Conegliano

![]()

...It is our mnemonic refuge.

I should explain this phrase by noting that I have never been particularly good at understanding myself to be in love. In effect, I never really feel myself to be in love with a person, but with what I suppose you could call that person’s hinterland—the place that they have constructed for themselves, expressive of their interests, but also of the accidents of their being. Their bedroom, their flat. I experience their places with a peculiar intensity.

—peculiar intensity—

– Self-Portrait, Between the Clock and the Bed

Edvard Munch

The apartment of the Venetian architect was a special case. She had rented it furnished, and, implausible though it must seem, she had not moved a stick of furniture since she moved in—a period of some four years. It was her books on the shelves, her pans in the cupboards, her clothes in the wardrobe, her toothbrush in the bathroom; but she had not, to note a peculiar example, taken down any of the paintings on the walls, nor put up any of her own. It was as though her personal space were made out in scrip.

I nevertheless registered an unusually penetrating (and as it turned out, delusional) sense of calm there. Perhaps I felt—as I did now in Hunter Sidney’s house—that I was a passenger, in transit, that we were cut off from the world together. Perhaps she stood out more conspicuously against that otherwise neutral foil.

Or perhaps I have just never got the knack of understanding things in terms of themselves. Readings must always be taken on an instrument of some sort.

It should be noted for accuracy that all the while I was with Veronica de Viggiani, Clarke was alternately drowsing and fretting on my sofa; so my sense of escape and refuge had a tangible, not to say rational, origin.

![]()

...It might fool the king of France...

The King of France was eager to retain the services of Camillo, and paid him a handsome retainer to that end. Camillo was eager in return that his secrets should be fully revealed only to the King in person.

Unfortunately for both, the need to have the entire arcane system of the universe translated into French threw the project and Camillo into fatal confusion.

Why this should be so, given that the hieroglyph is a universally obscure language, can only relate to the storage system of the theatre—it seems that behind each image were sheefs of printed and handwritten matter; presumably in remembering—seeing—where a particular tid-bit of knowledge was stored was also to know why; and that would act as a mnemonic prompt.

According to Viglius Zuichemus, writing to Erasmus an account of his visit to the theatre,'The King is said to be urging that he should return to France with the magnificent work. but since the King wished that all the writing should be translated into French, for which he has tried an interpreter and scribe, he said that he thought that he would defer his journey rather than exhibit an imperfect work.'

A familiar predicament.

—predicament—

–Portrait of Francis I

Jean Clouet

![]()

...Clarke is awake and restless...

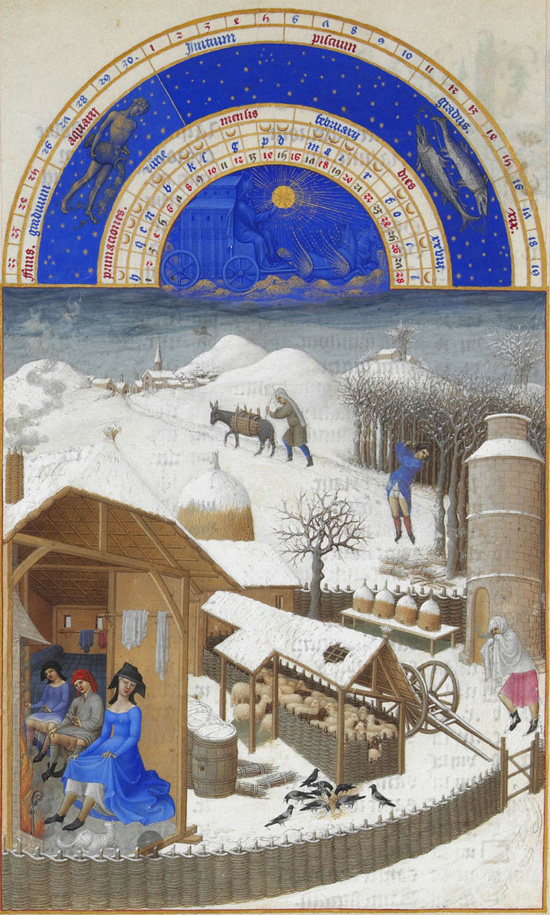

Clarke complains that he sleeps badly at the junction of late autumn and winter because the hours are 'out of shape'.

Before the standardisation of unit time, he argues, a night and a day were equally divided into twelve, regardless of their actual length. He is gifted, he further notes, with an ancient soul, and the hours at night in winter are in consequence to him lengthening and cracking; and since he also prides himself on being what he calls a 'brisk sleeper', it takes him some time to adjust to the sluggish night rhythm.

This is clearly nonsense so far as Clarke's broken sleep is concerned, but it is reasonable to wonder if those psalmodizing monks, for example, were alive to the slow stretched hours of a winter's night, or the corresponding briskness of the daily hours.

—briskness of the daily hours—

–Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, Folio 2, verso: February

Limbourg Brothers

![]()

Darkness is a thing...

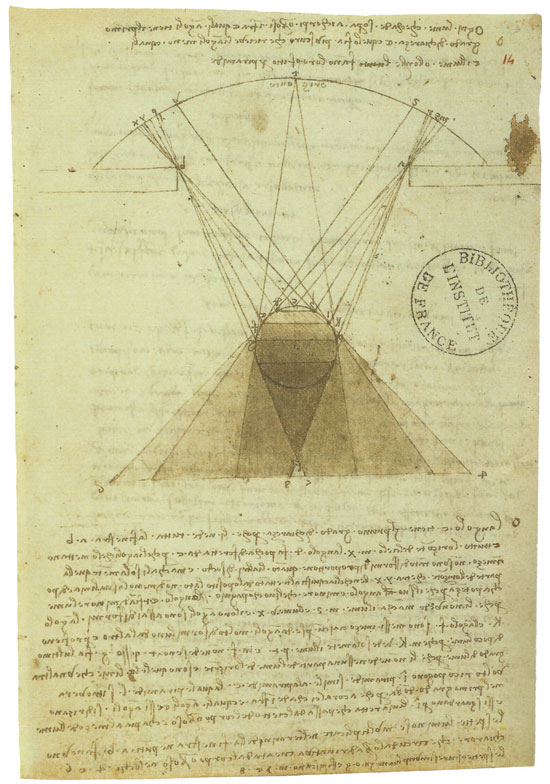

This, at any rate, is what Leonardo believed—that darkness or shadow is projected from certain dense and umbrous bodies, just as light is projected from certain other, lighter bodies—the sun or the moon, candles, halos, and so on.

—dense and umbrous bodies—

–light from a window on an umbrous sphere

Leonardo da Vinci

As Michael Baxandall notes:

"Being dense is the opponent of being luminous. Leonardo, at this time, [between 1490 and 1493] is even prepared to say shadow is stronger than light because it can entirely extinguish it, whereas light cannot entirely extinguish the shadow caused by dense bodies."

Shadows and Enlightment (1995) p. 152

It is doubtful whether Bruegel thought along these lines, but it is always worth remembering that dark, like cold, was a thing in the Renaissance, not an absence or a mere variant of light or heat.

![]()

...Citrus City

There is in fact already a Citrus City, located in Hidalgo County, South Texas. It had a population of 2321 in the census of 2010.

Citrus City was founded in 1943 by Howard Moffitt, a builder and architect and progenitor of the eponymous Moffitt style of house-building. A Moffitt house is essentially a cottage thrown together from salvaged materials—railway sleepers, for example, are used as beams, chair backs as scalloped eaves. Concrete is aggregated with found stones and broken glass. Stylistically the buildings are eclectic, homey, somewhat between an English cottage and a pairie adobe.

—thrown together—

–Moffitt Cottages, Iowa City

Billwhittaker at English Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

Howard Moffitt built most of his houses in Iowa City between 1924 and 1943, at which point he moved to Texas and founded Citrus City in response to a regional drive to grow commercial citrus crops—grapefruit and oranges.

Unfortunately, local irrigation proved too saline to grow citrus trees. There are no orange groves in Citrus City, in spite of the mournful litany of its street names—Lemon Lane, Tangerine Lane, Grapefruit Lane, Valencia Lane, Navel Lane—and the odd ornamental throwback.

![]()

...feel right.

A secondary, but equally exciting point is that this will be a mobile orange garden. The heavy clay pots of the orange trees will have to be placed on pallets with concealed castors and a braking mechanism, requiring of me a tiny feat of engineering. Engineering, I note with pleasure, is squeezed like oil from the compressed strata of necessity—of the accumulating populations of cities, for example, or in this case the multiplication of orange trees. Engineering is an ornamental practice (probably! I haven't given it much thought in my excitement).

Thus the garden will be not an emblem so much as an emblematic machine, rolled out on its wood and rope like some old Renaissance tableau of the Assumption of the Virgin or the Annunciation, all Angels Gabriel on wires and pulleys, gates of heaven shuddering open on iron hinges up in the apse, lanterns and costumes, hidden mechanism.

—wires and pulleys—

Angel Gabriel

Francisco de Zurbarán

![]()

...with a structured and structuring ornamentation.

For all Clarke’s rhetorical skill, which I have both preserved in spirit and improved in detail, I am forced to admit that I have the emphasis here somewhat wrong: the Palladian North End was not conceived as a bauble or toy to his new found daughter, but as a placatory gesture to his wife.

Veronica de Viggiani, the daughter in question, has told me something about her involvement with the Palladian North End.

She said that Kelley was already standing in the building site in atonement for various sins of omission—chiefly, failing to give his wife a child of her own, and failing to acknowledge his prior fatherhood—and was puzzling over blueprints, laying foundations, as though in this jigsaw of builder's materials some combination might be found to the conundrums of his life, when she confronted him for the first time.

They had been in touch by letter so it was not a complete surprise. Veronica was a student of architecture in Dublin, and she took her errant father now in hand: in her own words, she guided his builder's hand over the smooth logic of classical ornament, showing him mouldings and capitals in books, impressing on him the need for a certain bald simplicity and monumental directness, all to be derived from the most volatile-seeming decorative elements.

—guided his builder's hand—

St. Matthew and the Angel

Caravaggio (enhanced colour image, painting destroyed 1945)

And so the Palladian North End took shape. Veronica stayed with Kelley and his wife, unaware of any friction. And if the stand became hers, rather than Mrs Isobel Easter's, it was anyway never clear that Mrs Easter had ever wanted it.

![]()

...that is South London.

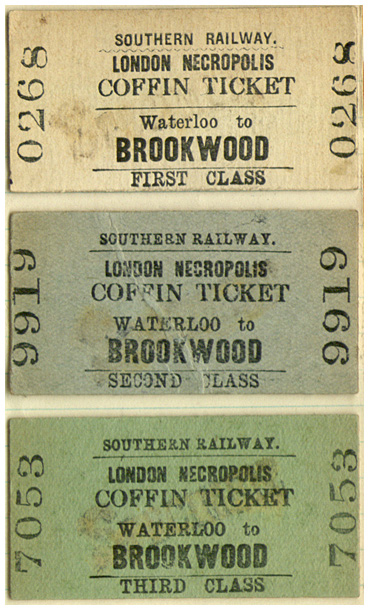

Burial of the dead is not now a mystical or apotropaic business, an appeasement of the ancestors, but a municipal infrastructure problem.

South London is where the city laid that problem to rest, a continuity of the dead rising to the surface here and there like beds of sedimentation: Surbiton to Kingston, to Putney Vale and Putney Old Burial Ground, Wimbledon and Wandsworth, West Norwood and Nunhead, Beckenham and Barnes, Camberwell Old and Camberwell New, Queen's Road and Micham Road.

And then there is the London Necropolis, the world's largest cemetery (once), served by a dedicated railway line and station, coffins become informational quanta in a perpetual and rhythmic shunting of the dead, of the dead, of the dead.

—all aboard!—

![]()

...men enjoying the company of naked women.

As it is, for example, in that direct descendant of the Fête Champêtre, Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe.

—guided his builder's hand—

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe

Édouard Manet

In the Manet the women are real and naked; not ideal and nude. If Giorgione was making a philosophical point, Manet is making a sociological one: men are typically only fully clothed in the presence of smiling naked women in the brothel or artist’s studio.

Both paintings are, however, part of the same managed biome; or, more precisely, Manet is taking a hand at managing with fire and oil, so to speak, a biome over which both he and Giorgione and any future Manet and Giorgione must graze their intellectual and aesthetic flocks.

To the horror of the townsfolk.

![]()

...a ritual cursus of sacrifice and desire.

On the blood-hyphen, Clarke is quoting Leo Steinberg, who discusses the trickle of blood which in various northern crucifixions and depositions joins the final wound in Christ’s side to his groin in contravention of the rules of gravity, making a typological connection between the final wound and the first—the circumcision.

—contravention of the rules of gravity—

Deposition

Hans Pleydenwurff

Clarke has a good deal more to say, about menstrual blood and the milk of the Virgin, but in the interests of cogency, if not of decency, I won’t go into that.

On the ritual cursus, Clarke's route is ahistorical. I very much doubt (from a careful examination of maps I found on the Internet) that the road up the back of the Janiculum was there in the sixteenth century. If such a cursus was in Bramante's mind, it would presumably have followed the route along the Via della Lungara, opened by Julius II. But this would have involved some tricky winding at the Trastevere end, up to San Pietro in Montorio.

—tricky winding—

Map of Rome, 1652

Matthus Merian (with additions by Civ Clarke)

![]()

...complex series of sortings...

Work on the doors had originally fallen on Giotto's recommendation to Andrea Pisano, who had produced one set (now on the south) beginning in around 1330. He had been under commission to produce a second set before financial crisis of the Bardi and Peruzzi banks and the Black Death of 1348 intervened. His doors would remain in the privileged position on the east of the building facing the cathedral until 1452, when they made way for Ghiberti’s second set. They now hang on the south side, gold on charcoal-grey like thermal-imaging of devotional or deific heat.

—thermal imaging—

South Doors, detail

Andrea Pisano

The competition to produce the second set arose in part from a rivalry between the Guild of the Calimala and that of the Lana (responsible for the duomo itself), who were currently decorating the west facade of the Duomo directly opposite the Baptistery, but was also linked in Florentine minds with the deliverance of the city from Giangaleozzo Visconti of Milan in the summer of 1402.

The competition panels (Abraham’s hand stayed by the angel of God) and the first set of doors themselves, with their troubled stories of vengeance and punishment and mercy deferred, may not have been conceived as a votive offering, but they were certainly translated into that mode by history.

![]()

...needed saving herself.

This is what Kelley is telling me, in so many words: it is time to choose, and to act.

He does not know, however, that Veronica de Viggiani, with whom all my relations now are mediated down flickering digital clouds, has taken an action of her own, and told her husband about her affair with me. This I have lately learnt down the wires.

To be caught in or to acknowledge an infidelity is one way of resolving uncertainty, on all sides. But it is imperfect. You measure the position of the various bodies, but still can only hazard guesses as to their velocity.

![]()

...whatever it is they seem loaded with.

In one of my first jobs, a summer job on a building site, I spent an afternoon shifting a stack of planks from one point to another, one plank at a time, each plank carried by me and a workmate my own age. The planks were neither heavy nor cumbrous, but I suppose my workmate and I were. Were both plodding and awkward, I mean—hence our foreman’s indifference. Under those planks, in the warmth of the sun, under the nothing weight of that nothing task, we were tidied away in his mind. We could do no harm, require no guidance, cause him no worry. If we were successfully resisting, then so was he.

—nothing weight of that nothing task—

Building of a Palazzo

Piero di Cosimo

![]()

...poring over the pages of butterfly books...

His lepidopterology was, if not exactly a literary, then at root a bookish pursuit. Nabokov recalled for the world that his interest in butterflies had been groomed by his practice of leafing through the pages of Maria Sibylla Merian’s book of illustrations of the naturalia of Surinam (Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, 1705).

—bookish—

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, Plate LX. 1705

Maria Sibella Merian

When he was eight, he brought a butterfly to his father in his prison cell (he had been imprisoned for political activities). Dead, presumably, the butterfly; although the idea of an eight-year old boy in sailor suit bringing a live, tame butterfly, perhaps gently pulsing its wings on the end of his finger, to his imprisoned father is hard to shift once it has occured to you. In the same interview in which he said that he hated concise dictionaries, he also said he did not care what sort of government a government was, as long as it did not encroach on the liberty of mind or body of its subjects.

![]()

...comparatively free to roam.

Just because you cannot see the walls does not mean that you are not banging your head against them, conceptually speaking: the park is a limited space.

The limits are both physical and conceptual. The wall marks the taxonomical divide: Park : non-Park. Inside the park, the deer belong to the Crown; outside the park, there are no deer.

And not just limited: privileged. To set a boundary is begin to sort those with access and those without. The Virgin has her walled garden, a preserve of holiness; as do saints in a sacra conversazione.

—preserve—

Virgin and Child with Saints and Donor

Gerard David

Walled retreats are proleptic of paradise: they are the VIP lounge of holiness. You need a pass to get in. Saintliness may need no protection from the smutched world; but it must be seen to be distinct.

![]()

...constantly re-writing itself, in the register of births and deaths.

In my case, quite literally. I have learnt, and just now divulged to my drinking companions, that Veronica di Viggiani is pregnant with my child.

There is no question of keeping or not keeping the child. This child will come. He, or she, has found him or herself by chance or timing on the right side of a line of demarkation. These things are not susceptible to logic, only to instinct, judgement, circumstance.

This proto-child has thus fallen, for the time being, into one of the two great super-kingdoms of being, overlying even Clarke's Animule, Vegetebule, Minerule: the existing and the mute choirs of the non-existing.

![]()

...contemptible under every point of rational regard.

But I quite like it.

—contemptible—

St. Giorgio Maggiore

The Redentore, also, is a building of idiosyncratic beauty, with its double pedimented facade, and its interior of uninterrupted Corinthian, white marble and pietra serena. Both buildings are intently thought through and worked out, and pious in their way.

Which leads me to wonder, somewhat defensively, what Ruskin would have made of Norbiton.

![]()

...and pacing its streets in person.

Since Euler shuttled in his career between St. Petersburg and Berlin, it is in fact highly likely that he stopped by Königsberg. Perhaps the people of Königsberg accorded him the freedom of the city he had, in essence, solved. The freedom to come and go over its bridges.

Attentive readers will recognise Euler as the pioneer in the mathematics of column-buckling whom we met in Priapic. He was blind or almost blind in one eye—a malady he blamed on his cartographical work for the Russians in St. Petersburg—and Frederick the Great liked to call him Cyclops, not wholly in affection, since the great mathematician had tried and failed to get up a head of water for a fountain in Sanssouci, as the peevish monarch relates:

I wanted to have a water jet in my garden: Euler calculated the force of the wheels necessary to raise the water to a reservoir, from where it should fall back through channels, finally spurting out in Sanssouci. My mill was carried out geometrically and could not raise a mouthful of water closer than fifty paces to the reservoir. Vanity of vanities! Vanity of geometry!"

Letters of Voltaire and Frederick the Great, Letter H 7434, 25 January 1778

—Cyclops—

Leonhard Euler

Jakob Emanuel Handmann

![]()

...looking for an angle.

As usual with Kant, there is a bit more to it than that. He in fact believed that geometry offered the user a series of synthetic a-priori judgements, and was looking for something similar.

But, understandably enough, he had not accounted for non-Euclidean geometries. So in fact he walked about Königsberg in a great cloud of unknowing, a cloud more dense than he could easily have imagined, surrounded by invisible swarms of the irrational, like an illiterate inhabitant of Borges’ library, so many angles dancing like angels on pins.

—invisible swarms of the irrational—

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (preparatory drawing)

Francisco Goya

It is only natural to wonder, therefore, about Norbiton's own blizzard of unknowables.We have been called dense, thickety, a thorny prickle of words; but we are a balm, a salve, a caress to the unknown elements which lie beyond our ring of fire.

![]()

...a dead child.

Clarke is recalling the words of the artist Christian Boltanski:

"I began to work as an artist when I began to be an adult, when I understood that my childhood was finished, and was dead. I think we all have somebody who is dead inside of us. A dead child. I remember the Little Christian that is dead inside me."

To print a book, after all, to publish something, is to die a little. Like a moribund pope (is there any other sort?), you watch them—the craftsmen, the editors, the graphic people, the printers—building your mausoleum; assembling your impulses and little jolts of feeling into standardised slabs and bricks. Line them up on your shelf, your publications, and see yourself writ there in stone.

![]()

...only at their death.

Linda Donley-Reid, conducting ethnoarchaeological fieldwork between 1979 and 1981 in Kenya, met three Swahili women belonging to a class known as wa-ungwana who had been born and spent the entireity of their lives within the nests of walled courtyards and inner rooms of their houses; they would only leave when they were taken to be buried. The house was a traditional wedding-gift to a bride, and was her property, and could only be inherited by her daughters.

I tell Mrs Isobel Easter this when she stops by the house to supervise our move, and she thought for a moment, and said, "why do they have to take them out of the house when they bury them? Why can’t they bury them under the floor? I would like to be buried here, perhaps not under the floor, but in the garden."

I am forced to explain that in these Swahili houses there is indeed a private ritual space, known as the ndani, where, among other ritual activities, the blood and intestines of the deceased were traditionally strained into a pit before the body was prepared for burial and carried out.

Mrs Easter may be at peace with her agoraphobia, as I have related elsewhere; but there are different ways of making peace, and removing your army from the field of battle is not the only one.

![]()

...perpetually wandering early humans...

This is a summary so swift and efficient it tends inevitably to the incorrect. The humans who preceded these first farmers and settlers were no more perpetually wandering than Cane or the Flying Dutchman. Rather they oscillated in complex but to them anyway rational patterns, between in-camp and out-camp, between summer meadow and winter coast, or between points abreast spring or autumn migratory routes of deer or bird or fish. They moved, in other words, when they moved, over a settled landscape.

They were easy come, easy go with their domesticity. When the resources of a camp dried up, they packed up and moved on; likewise, if the detritus and the midden mounted, or if someone died. That they were easy to dislodge, however, does not mean they were unsettled. They moved on; but they knew where they were going, and with whom, and why.

This, in sum if not in detail, is what Ted Kelly says to me when – he having brought in and deposited a small box of kitchenware on the kitchen floor – I show him our flagstones and the snail on the hosta. What he actually says – "feels solid, doesn't it? Permanent-like. But it is much less solid than your eye tells you; that snail will still be there when you pack up and move on" – is as close as he ever gets to telling me to do right by his daughter.