Ornamental

—matted jungle of ornament—

– Orange Tree,

Matthew Roy Coleman

The ruins of Norbiton: Ideal City are overgrown now with a matted jungle of ornament. The ornament, if anything, holds the crumbling structure in place. The ornament is the city.

Perhaps that was all it ever was, all that rational superstructure—a framework for life to take hold, an invitation to fecund irrationality.

A city, after all, is nothing but a prosperous and inventive shanty town.

![]()

Were I to design a city from scratch—and I have tried and failed once before, so I know what I am about—I would begin by planting orange trees.

Perhaps I would only plant orange trees. Presumably a city in the form of an orange grove would in time generate its own internal structure—tool sheds, propagating greenhouses, benches, walks, box, borders, lawn. I do not know if you can pleach orange trees, but the trees might be encouraged to entwine in natural or crafted bowers, offering shelter to the city’s inhabitants in heavy fragrant festoons and swags.

Approaching the city from the country you would know that you were close, that you had entered it, in part by its scent, its airborne opulence; but in part by an almost imperceptible ratcheting of geometrical order. You would see spherical oranges suspended within managed—and perhaps at the city centre, topiary—foliage.

—ratcheting of geometrical order—

– Orange trees at the Villa Doria Pamphilj

You might however, out of season, pass through its entire length as though through a half-dream of urban space, a city caught out of the corner of your eye, going on behind your back. A city manifesting itself as a subtle change in the reflectivity of green, in the density of certain hues. Perhaps you would conclude, there is no city here. And arguably you would be right. After all, it would be a seasonal city, a city that was only truly a city when in fruit.

Welcome to Norbiton: Citrus City.

![]()

Needless to say I would not really begin by planting orange trees—that would be insane—but I would, I think, always be working around them. They would be, in my mind’s eye, the ornamental fulcrum of the finished city.

—ornamental fulcrum—

– Allegoria Sacra,

Giovanni Bellini

By ornament I mean something more than mere decoration. Decoration is applied to a structure or a surface—thus a body is tattooed, or the top of a cake is iced and sprinkled.

With ornament by contrast there is no distinction between surface and decorative motif, say, or between structure and adornment of that structure: a painting is not a decoration of a canvas so much as a fully-realised ornamental object.

Further, while a painting can be thought of in non-ornamental terms as a system of masses, volumes and implied space—a composition, in other words—such structural elements are not in some sense coded in the painting, concealed and revealed by the layers of paint; we do not begin with the painted surface and read through it as though it were mere decoration, penetrating to more profound structural depths. Rather, the two are knotted together, each emerges from and controls the other.

![]()

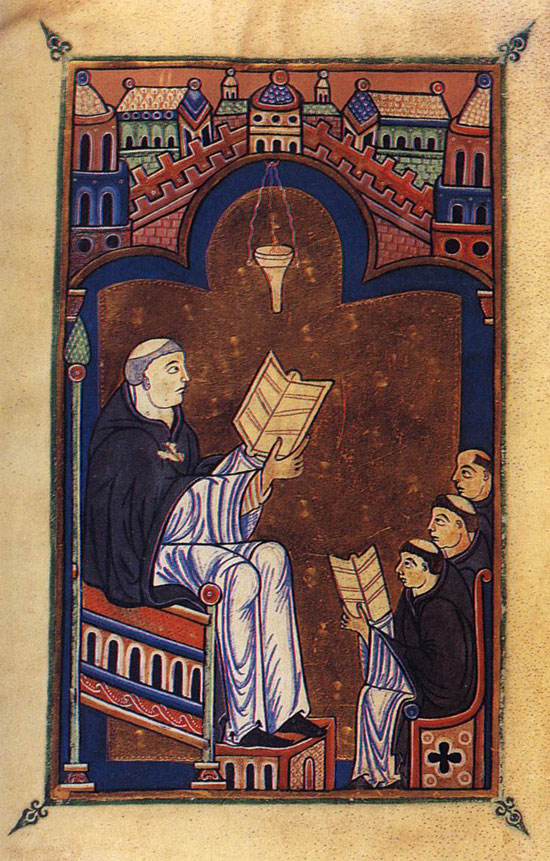

Ornament, to the old philosophers—Hugh of St. Victor, St. Basil, Bernard Sylvester—is a sort of helix of information floating through the cell-space of the cosmos.

—helix of information—

– Works of Hugh of St. Victor,

Unknown Miniaturist, French (active 1190s Paris)

They understood creation to have happened in two stages: first, the generation of inform matter; then, a clothing or adornment of that informness, which they called exornation.

Ornament and order after all, like cosmetics and cosmos, have the same root. The plasmator god does not finger-click the world into existence; he is perpetually squidging it, shaping it, moulding the undifferentiated clay of the universe into patterns, forms, entities, doodling round its margins, stretching it out like gum in an automatic but directed and repetitive process.

![]()

To repeat, there will be no orange city. I am done with founding cities. If a city should one day emerge around me so be it, but my ambitions now run in other directions.

I am standing to one side of Tony dell’Aquila’s garden, surrounded by small orange trees, considering their placement and arrangement within the ramshackle structure which I have designated the orangery—a semi-greenhouse leaning against the north wall. Dell’Aquila’s garden is to be finished at this side by a cluster of ornamental trees.

In the appropriate season, four of these trees will be dragged out and positioned at and embedded within the four corners of the parterre mazes of the garden, or around the flat pond, trimmed to neat globes of topiary foliage, echoing the form of their globular orange fruit.

—around the flat pond—

– Orange trees at the Villa Doria Pamphilj

The remainder of the trees will stay in the orangery with their foliage left naturally to straggle, a contemplative drift of leaves. The intended effect—of controlled and projected ornament (single ornamental objects) spilling from a reservoir of footloose horticulture (the orangery)—will perhaps be lost on the casual viewer. Even dell’Aquila looked blank and to a degree impatient when I talked him through it.

But it will feel right, because it will be a diagram of ornamental order.

![]()

A garden, like the universe or an individual’s life, needs time freely to ornament itself. Sufficient time for the patterns of slow work to assert themselves.

Slow work is work that has no end—distinct from the job, the task—or at least no end in sight. You are occupied with a thing not because it relates to an end, but for itself. Your work has no horizons.

Not that it does not have shape, or direction, or history. It will be unmanaged, but not ungoverned. Your progress, the change unfolding around you as a result of your work, is real: but it is also imperceptible. It is as near as you will ever come to what I suppose must be the temporal rhythms of paradise, where logical sequences of actions bob around on oceans of possibility.

And it is worth remarking that creation, under the terms laid out by medieval philosophers, was a slow and everlasting work.

![]()

Hymn-singing in isolated communities is a version of slow work: congregations singing hymns unaccompanied will tend over time gratuitously to ornament those hymns.

It is an emergent property of communal hymn-singing. Some singers get left behind, are never up with the pulse; abler singers have to linger on a note, kick their heels as their peers catch up; and so they start to make their approaches stepwise, interpolating new notes, or they vary the note they are lingering on, make little arabesques, little aural doodles on it. These ornaments might in turn resemble to the ears of the weaker singers still other hymns (since all hymns sound alike), so that, over generations, hymn will be grafted to parallel hymn. Community singing breeds ornament like foliage around the written notes, ornament that in time becomes standard, displaces the tune.

In some traditions, bold young singers—known in the Mennonite tradition as vorsänger—are appointed to take the lead in the congregation and transmit the accreted ornaments down the generations, so many Rococo fractal oddities spinning through aural-history-space.

The result is a style of singing known variously as the Old Way or Oole Wies, a florid take on traditional chorale or hymn tunes particularly prevalent in isolated communities of Anabaptists and Mennonites in Germany, Poland, Silesia, and in many parts of the United States. Valued ornament emerges from the undifferentiated chaos of bad singing.

![]()

In Nocturnal (here), I suggested that early monasteries at night were places of specifically aural contemplation:

"The darkness of night, to the sleep-deprived early monk, was an analogue of the pre-creational chaos; their psalmody—the settings of the psalms of David—was in consequence spun from that chaos, a songlines of melismatic creation. The night was articulated, given shape, through the hypnotic and endless, but not self-same repetition of the Psalms."

It seems in fact to be the case that a process analogous to the Oole Wies of the Mennonites was at work in those cold monastical centuries, the monks making slow work of their psalmodic vigils. It is a dragging business, intoning endless psalms in the cold night watch. And so the antiphons and responsories of the chants were characterised by melismatic ornamentation—a prolonged wandering on a single syllable.

In time there was a firming of purpose; musical minds like those of the vorsänger saw to it that the most evolved melismas developed a life of their own, had words set to them as mnemonic aids which in turn became distinct songs, calved like icebergs from cold continents of chant, free-floating melodic units set loose in music-space, becoming hymns, anthems, seedbeds in turn for new ornamentation, new calvings. Music slowly proliferates itself.

![]()

I began by noticing that the tumble-down ruins of Norbiton: Ideal City are now overgrown with ornament, and that the ornament holds the crumbling structure in place. I was thinking in part of the stories, and you might say the proliferating myth-cycles, which have accumulated around it.

Stories are not bricks in a city’s substructure; they are told, forgotten, retold, embellished, purified; they are ongoing ornaments of the city. And in the case of that most diaphanous of places, Norbiton: Ideal City, they are to all intents the city itself.

A case in point is the story of the building of the Palladian North End—a sort of macro-ornament (which is mostly how I understand architecture) in the form of the celebrated football stand which graced Norbiton FC’s Kingsmeadow football ground for a single season towards the end of the 1980s.

Clarke, sitting on a low wall in dell’Aquila’s garden and eating his lunch—he has brought a compartmentalised sandwich box with a ham sandwich, a hard-boiled egg (the salt wrapped in an envelope of greaseproof paper), and some salad; I take these shoots of organisation to be a sign that his six-month depression, triggered by the destruction of his apartment and belongings in a fire and exacerbated by the death of several close friends, is finally lifting—tells me between hippopotamean mouthfuls what he remembers of the ornamental system of the Palladian North End.

It was a classical—or classically inspired—structure, modelled, as I have related at elaborate length elsewhere, on the Pazzi chapel in Florence (hence not Palladian in the least).

The logic of the classical style is that it strips away gothic accretions: animals on capitals, vines creeping around columns, all that jungle ripeness, feline overgrowth.

But the classical is not an enemy of the ornamental: classical ornamentation under the Vitruvian system encodes the building; the various proportions of the capital or the column width or the increments of the spiral of the volute will determine the spacing and the number of columns, the dimensions and volumes and masses of the building.

The classical moulding on the Palladian North End might not have been sculptural, pleasing, even competent—Clarke recalls some ham-fisted volutes on what I have described as the 'fuckwitted capitals of the Norbic order'; and it cannot be said to have generated the building as a whole; but neither was it gratuitous.

If the Palladian North End emerged from the mud and confusion of a bankrupt and abandoned building site, then it emerged as a bubble of order. The plaster of the moulding was fresh white, and seen from a distance—across the ground—it looked clean and impressive, it had an organising clarity of purpose.

A clarity, says Clarke in parenthesis, cracking his egg and unsplintering its shell, which masked some knottiness in its genesis, the precise multi-dimensional geometries of which he could not follow, but which in some way involved Kelley’s illegitimate child, Veronica de Viggiani, who returned to Kelley's life at about this time.

![]()

Whatever else it might be or become, a child is an ornamental knot of its parents’ hitherto indefinite existence, a whorl of pre-existing material and fresh potential, a minor but vigorous reconfiguration of the cosmos1. Little wonder, then, that it solicits chiming energies from its parents; parents suddenly hurry to make things, shape an environment.

That Kelley only met his child when she was a grown woman made a difference, certainly, but not a fundamental one. And if she made a chaos of his world for a short time as all children do, then it was an opportunity for him to build something with a purpose. He dressed the universe—his diminutive universe—with a structured and structuring ornamentation.

![]()

There are in the world ornamental objects (dwarf orange trees, for instance) and there are systems of ornamentation (orangeries).

A Bach fugue is a system of ornamentation: specifically, it is the elaboration (elaboratio) of an invention (inventio). The invention is the fugal subject, the information, as it were; the elaboration is the working out of that fugue2.

Given a sufficiently promising invention (fugal theme), the process of elaboration will appear potentially infinite: as long as the player has hands with which to play, the piece may continue to unfold like a fractally self-similar Rococo tendril.

—continue to unfold—

– detail of stucco in the Weißer Saal, Würzburg,

Antonio Bossi

The elaboration of the invention is not arbitrary or whimsical; it is governed by the logic of the invention itself and by broad respect for the rules of counterpoint.

Thus what is agreeable or consonant is partly a function of the social, of the general fugal environment; not of the inherently (organically) aesthetic. Invention and elaboration are terms derived from rhetoric—speech has its ornaments, and what are ideas if not the ornaments of thought?—and rhetoric is a social practice, the rhetorician speaks to a gathering.

And I suppose it is for this reason—if I have followed my own argument—that I am moved to imagine my orangery not as a retreat (this lime-tree bower my prison!) but as an elaboration of a city where each day lived is a permutation of some original felicitous invention: logical but not determined; unmanaged, but not ungoverned.

![]()

“I am a topiarist at heart, and my love for clipping things sometimes amounts to a mania.”

Igor Stravinsky, on Cocteau’s libretto for Oedipus Rex

![]()

In performance that Bach fugue would not be ornamented as such3: the learned style, of which the fugue is an instance, does not require it. But in keyboard music of the galant style (dance suites, for example) the performer would enliven his playing with the appropriate graces and mordents and decorations, so many interstitial tendrils of sound.

These ornamental devices were not structurally rooted; that is, they do not emerge by some structural logic from the piece being played; rather they were agreed by convention (and sometimes explicitly codified) within national school—the French school of ornamentation, the German, the English, and so on.

Thus, as with the expansion of a figured bass, it was in performance, not on the page, that the piece took form: a layer of conventional ornament (so many rhetorical figures) overlying a structural base which was itself mobile, ornamental. The performed piece is a scintillating and transient presence: a presence of which the notated score is only a sketchy memory.

![]()

A sketchy memory, but also a hobble to the permutational wandering of the oole wies variety. Musical notation both restrains free melismatic wandering and encourages it: elaboratio can only be of a static musical object. The musical object becomes, written down, an object of contemplation, becomes a piece.

Music, like life, is something you do; but then so is a painting, or a piece of writing, or indeed a bridge or a football stand; or for that matter an orangery. An orangery sits immobile in the sun, sweating perfumes, geometricising; but it is a done thing, not the imprint of an action but the considered action itself, laid out in amber.

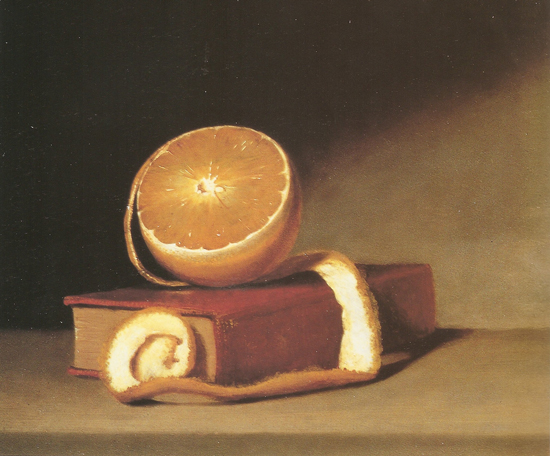

Clarke has finished his sandwich and his egg, and is now peeling an orange—not plucked from my ornamental trees: he had it in his pocket.

There are various ways of eating an orange. You can simply quarter it and suck out the juice (efficient), or you can top it, crush it, and drink the juice as from a coconut; or you can slice vertically through the peel and pull it off with your thumbs; or you can do what Clarke is doing with a sharp penknife—cut rotationally so that you are left with a spiral of peel; then strip back the pith and deposit it in the shallow spiral cup. You can chuck the pips in on top too. The orange has been anatomised, a testament as much to the sharpness of the knife as to the succulence of the fruit. The universal tendency of an eaten orange to entropy has momentarily been arrested in the very instance of its dissolution.

—arrested, momentarily—

– Still Life with Orange,

Raphaelle Peale

Anyway, as he peels and eats, Clarke recalls for me a picture of orange trees he saw painted in Rome by an American artist of his acquaintance, Matthew Roy Coleman, who generally worked in whatever scraps of media he could lay his hands on. He would paste torn out sheets of books found in dumps to old bit of plywood with rabbit skin glue; he would mix collage and drawing and paint. Everything had a scurvy East German industrial sort of feel; it was a world of Heath-Robinson contraptions and perpetual anxiety. This anyway is how Clarke remember it, twenty years on.

On one occasion, when Roy Coleman had been struggling for a while with a sketch for a tripod contraption of some sort which was mutating, in his own words, from a plan into a contrivance—he found himself doodling an orange tree over the top of it. He was thinking, he said, of the orange trees in great terracotta pots which stud the parterre maze at the Villa Doria Pamphili in Rome—alluring, but unattainable, like his fugitive notion of the tripod, perhaps.

Oranges are a carpologically unstable plant, given to mutation or variation of hybrid; in the same way, there is a mutational or permutational relationship between the Coleman tree and its smeary tripod forebear. I do not know how the one springs from the other, but I do know that nothing springs fully formed into being. Every invention is the elaboration of some prior invention. There is no meaning in ornament. Ornament only gives the illusion of meaning because ornament is patterned; cut through it and you find a continuous pattern, and you assume that it is evidence of a fundamental structure. There is no meaning, only a self-interfering structure of knots and whorls; ideas, meaning, belief, the compressed thickness of an entire life: all are ornamental, a function of patterns of repetition and variation, arabesque and acanthus, a repertoire of techniques which over time shifts you from here to there.

It is not meaning you should be groping for, as if it were a root in the soil of your being; not meaning, but permutational possibility. Down among the shivering atoms of daily life there is always the possibility that something felicitous or consolatory might suddenly appear, and appear as if fully sprung, as if something has undergone some sudden change of state. But it will be the product of the infinite number of shuffling permutations, moment to moment: it will be, in some sense, meant.

And so I clip my orange trees, clip them leaf, bud, stem, rotate their pots, position and reposition them; and stand back, just to see if something is emerging; just to see.

—just to see—

– Orange trees at the Villa Doria Pamphilj