Priapic

—magesterial control—

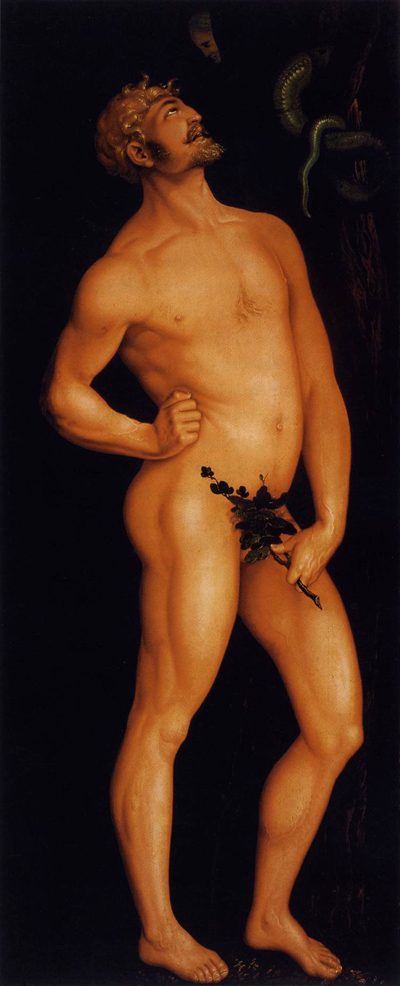

– Adam and Eve (detail)

Hans Baldung

Adam, before the Fall, exercised magisterial control over his penis. He could ready it for procreation as an act of Will, in the same way that he could lift his arm over his head. There was nothing to it.

This was the finding which Saint Augustine, after a great deal of muddled introspection, announced in his encyclopaedic City of God Against the Pagans. It was the only logical answer to the problem of involuntary causation.

That I know of, Augustine had no comparable theory regarding the physiology of female arousal, but this is hardly surprising: here was a man whose understanding of the sexual impulse was directly indexed to personal emotional pain. It was impossible for him to abstract himself from the circuit of his own desire because his desire, like his God, was formless, inscrutable, everywhere.

![]()

Hunter Sidney (decd.) wrote a story (unpublished) in which Adam, striding naked one day around the garden, finds his way into one of its shady corners, somewhere dank, mossy, overgrown; and pushing back the branches discovers not a snake, not an apple, not an inexplicable female, but a hidden antiquity, a statue of Priapus, god of the huge penis, of gardens and fecundity.

—not a snake—

– Priapus, or Bes

Ephesus

Eden, in Hunter Sidney’s odd vision, is built over a substratum of unknown and ancient desires, tell-tale fragments of which occasionally reveal themselves, relics of an older, more knowing, people.

Adam, having as yet no historical sense, would have made nothing of it. The statue to his incurious eyes would have been no more than a representation of an anatomical outlier, a man idly flexing his giant penis.

I do not recall how the story concluded, but I do remember Hunter Sidney glossing it for me. Priapus, he said, is an ancient god, much older than Adam, cogate with the Egyptian Bes, among others. Adam’s penile acrobatics were not evidence of a clean physiological and psychological slate, but a form of monkish control. And the near perfect fit between inclination and reciprocation was nothing more than a streak of luck, as he was about to find out.

![]()

Hunter Sidney understood that the garden of desire is a garbled, unreadable tangle1, periodically illuminated by lurid flashbacks.

—lurid flashbacks—

Take Tony dell’Aquila, in whose garden in Richmond I now stand. Tony’s garden, laid out to my specification, is a model of quiet order, a geometrician’s modest delight. But it turns out that it is part of a larger and more troubled system. Tony has built it—and his summer house, now erected in time for winter—as a deliberate counterpoise to the garden (and summer house) of the woman he loves, my patroness, Mrs Isobel Easter. It is a winter garden of solifluctions and tumid damp earth to her (in his atrophied imagination) early summer garden of sweet air and fresh flowers.

He is excited, because he had always supposed she would never again venture out.

Now he knows, from me, that she has come out and is abroad in the World. What had been one part of an imaginary tribute, an invisible cosmic wiring—his garden—has from one day to the next become a place she might see, in which she might be seen. To see and be seen is to act, like it or not, in the Theatre of Desire. And so Tony is organising a stage for her arrival. She has made no suggestion of coming to visit, but he is adolescent with excitement.

I regret now the absence of a statue of Priapus.

![]()

Priapus was a local god, a household god, from Asia minor2. Not for him a mountain-top remove. He stood scarecrow or guardian of the house, or in your garden, his ithyphallic presence an entertaining burlesque on your own fading, patchy desire. Something to hang your hat on.

Because your fumbling lust is funny. Priapus himself was a victim of his own foolish desire. Ovid tells in the Fasti how, at the feast of the gods, when everyone had nodded off, the vigilant Priapus stole up to the object of his lust, Hestia, meaning to rape her; but the ass of Silenus brayed, everyone woke up and laughed because, well, there stood Priapus.

—there stood Priapus—

– Feast of the Gods (detail)

Giovanni Bellini

Priapus does not have an erection: he suffers from one. He may in this instance have lighted on the available (because unconscious) Hestia, but it could have been any other. His lusts are quaquaversal, it matters little what their direct is. He is subject not to yearning, but to craving.

So you set him in your garden, part of the flotsam furnishing you acquire over a lifetime. His version of desire mirrors our own, because our desires and lusts are for the most part no more than passing moods which may or may not leave a (humiliating) trace in our history. Desire somehow just happens to you. It has no meaning, and no shape. Meaning is reserved for the sated, slumbering gods, whose transient fancies inspire songs, bring down city walls.

![]()

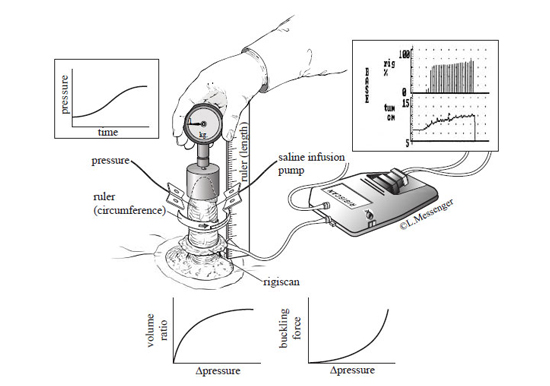

The erect member, in other words, is an unreliable index.

What can we say then about the biomechanics of the male, rather than the deific, erectile function?

We know, at a level of detail beyond St. Augustine, that the success or failure of the male erectile function depends on the timely organisation of mechanical forces—both fluid and structural—rather than the summoning of some psycho-spiritual effluvium.

There is a chain of (non-intentional) causation. The brain sends a signal stimulating the release of nitrous oxide, a neurotransmitter, which in turn relaxes various tissues (I forget which), allowing increased inflow and restricted outflow into the two lacunar spaces of the corpora carvarnosa of the penis.

Thereafter, the penile column must resist a tendency to buckle in the presence of an axial force (e.g. fucking).

—resist a tendency to buckle—

This much is clear.

But this simple mechanical procedure is fired by a sparking, sputtering, smoking circuit board. The outward signs of male desire correlate weakly to the presence (mental or material) of the object of desire. If Priapus and Adam, strongman and gymnast respectively of the penis, stand at the extremes of such a correlation (0 and 1), then actual human males veer freely between the two.

Just as the flaccid penis is not an indication of the absence, so the erect member is not a reliable pointer to the presence, of desire. For this we have the evidence of Priapus, certainly, and of Christ, whose tumescent member in rigour mortis some critics3 have taken as an emblem of the incipient triumph of life, since putrefaction was thought to begin in that region.

And there is also the evidence offered by experience. Clarke claims he was once slapped by a girlfriend for patiently explaining in the midst of an embrace that just because he happened to have an erection, it didn’t mean he wanted to have sex. Less perversely, all males of the species periodically experience a matudinal hard-on, where some imbroglio of trapped limbs and the smoke of dreams has caused best-guess diversion of blood flow. And so on.

The erection, then, is a temperamental performer. It requires a stage. Flattery. Costumes and greasepaint, perhaps. But above all it requires you to clear your throat, throw on some bombast, and get in character.

When all that is in place, the erection can makes its grand insouciant entrance like a general on a horse, rallying and marshalling your hitherto scatterbrained desire. We can expect skirmishing, oratory, discomfiture, a turning tide, and, if we are lucky in the end, a little catharsis.

—like a general on a horse—

– Gattamelata

Donatello

![]()

In Norbiton: Ideal City, as in Eden, there was never much question of galloping appetite. The streets were broad and empty, fit for monks and melancholics, not for prowling lovers. Clarity of mind was substituted (in our imagination) for the humiliation of unrequited desire.

But desire, in its confused way, is now reasserting itself. Clarke feels it. Clarke of late has been a sort of anti-Priapus, a slothful pudgy unstirred being, a Silenus perhaps, who has lain semi-snoring on my sofa since his flat in Madingley Tower was gutted by fire, as though that consuming element had oxidised also the wood of his virility.

But now he is moving. Mandy, his girlfriend, who has been in Liverpool with her family since the fire, is coming back. So Clarke is sitting up on my sofa, sniffing the air, scratching his intellectual armpits.

I live in hope that he might yet be fully dislodged.

![]()

For now, Clarke has accompanied me to Tony’s house, to do a bit of devotional tidying around the summer house.

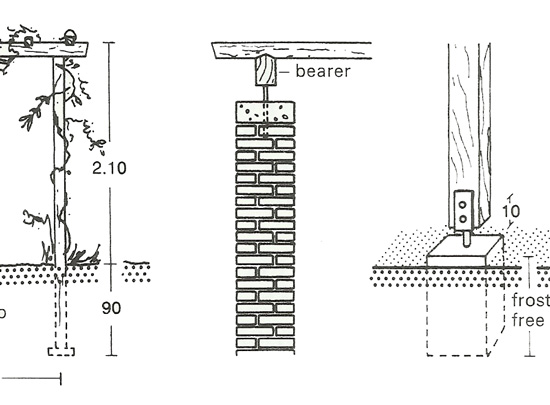

Tony dell’Aquila's summer house—really, not much more than a roofed pergola—is a series of eight brick columns on a concrete dais with wooden deck (which Tony, on his knees, is varnishing while we work), supporting a flat or very slightly inclined tile roof on wooden crossbeams which overhangs the dais. Inside there are benches and a stone table.

—not much more than a roofed pergola...

We are to work on clearing a space that is intended as a grassy precinct around the structure, but is currently a mess of spilt building materials and spattered tarpaulins.

Before we can do that, however, Clarke has to walk up on to the dais, peer around the structure, and tap one of the columns with his knuckle approvingly.

![]()

I am confident that Clarke knows nothing of column buckling theory. And to judge from the number and thickness of columns dell’Aquila has used, neither does dell’Aquila.

Column buckling theory is based on the work of Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler (1727-83). Prior to his intervention, supporting transverse beams on columns was, in engineering terms, guesswork. The Greek temple, or the Egyptian, with their forests of columns, represent an over-engineered solution, much like their cosmology.

In an ideal world—a world informed by practical understanding—you would be able to thin the columns, winnow them, support the building on an exact calculation; there would be an accurate and fully discriminated balance of materials, weight, opposing forces. Brunelleschi, you feel, had an intuition of this, with his slender mousebone columns.

But dell’Aquila is all belt and braces. No mousebone calculation here. Just bricks piled up, bricks and more bricks. If this is a theatre of desire, then in its small way it is one of Egyptian ambition.

![]()

While we work, Clarke talks me though his theory of Egyptological Desire in the city of Rome. Renaissance Rome, he says, the Rome of the Popes, was a great Theatre of Egyptological Desire. And the engineer of that desire was Bramante.

Bramante conceived of Rome, says Clarke, as a linear city, a hieratic procession along a single line running from the Tempietto down the Janiculum, through St. Peter’s and the (re-positioned) Vatican obelisk, into the courtyards and gardens of the Belvedere.

This is largely incorrect, but I give Clarke his head.

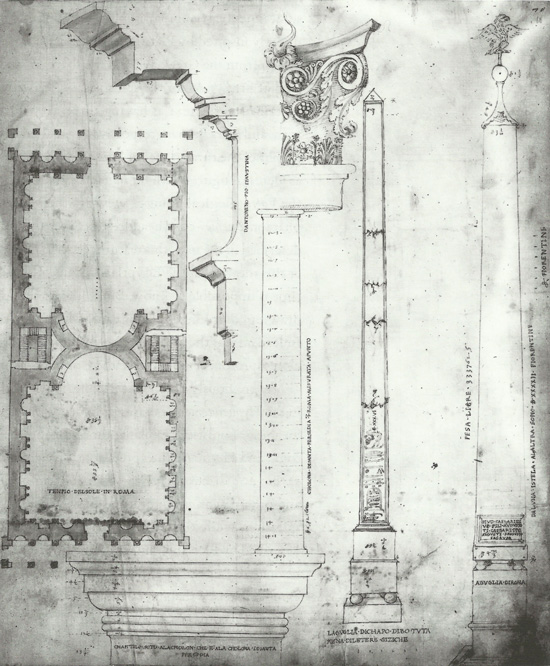

It is well known, he says, that Bramante wished to spin the new St. Peter's, for which he was the commissioned architect, on its axis, bringing it into alignment with the obelisk which at the time stood to the south of the old basilica and which, according to the mid-twelfth century Mirabilia urbis Romae and subsequent legend, contained the ashes of Julius Caesar in the brass ball at the summit; or failing that, to move the obelisk itself—there is a sketch by Giuliano da Sangallo, which measures the dimensions of the obelisk and estimates its weight at 333762.5 pese libre.

—333762.5 pese libre—

– Vatican and Capo di Bove Obelisks

Giuliano da Sangallo

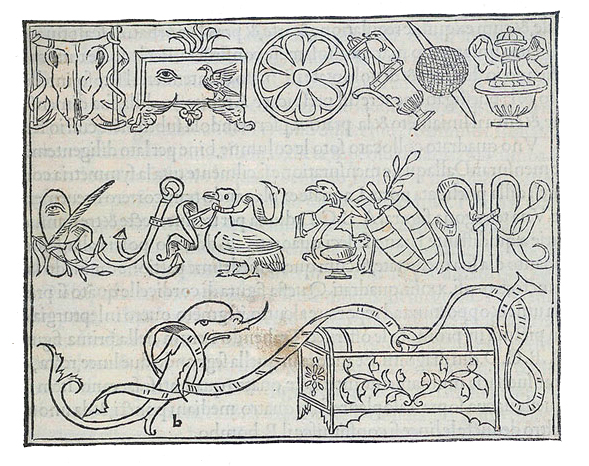

It is also well-known (if you have read your Gombrich4) that Bramante wished to carve a hieroglyphic rebus of his own devising into the frieze of the Belvedere, analogous to that in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili of Francesco Colonna (1499).

Julius II, not wholly insane, vetoed both proposals.

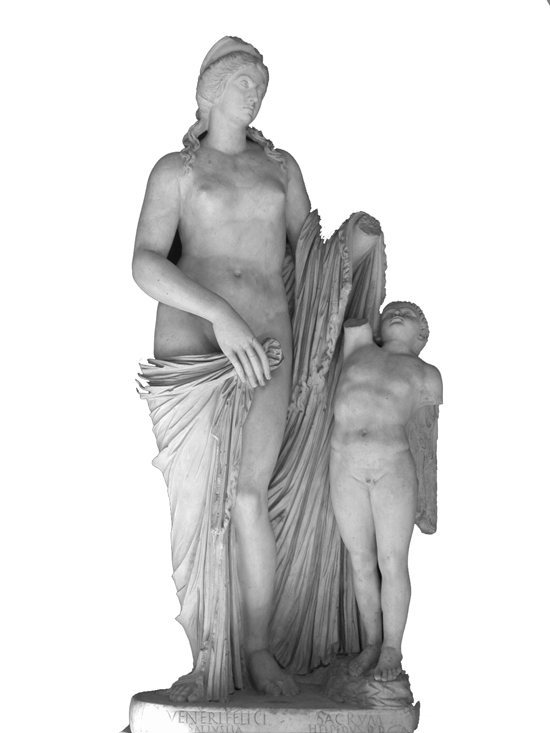

The analogy with the Hypnerotomachia suggested to Gombrich that Bramante was intent on creating a complex of buildings through which the neophyte would make a labyrinthine progression to St. Peter’s, via the obelisk (divine tuning fork), from the gardens of the Belvedere (a pagan grove to Venus according to Gombrich5, whose classical statue groups culminated in the Venus Felix).

Profane to sacred. Or the other way around, depending on your mood.

—depending on your mood—

– Venus Felix

![]()

All this, to repeat, is well known. But Clarke has a refinement. He brings the argument back to the Tempietto, the martyrium built on one of the two supposed spots of Peter’s inverse crucifixion.

—martyrium—

– Tempietto

Bramante

The two sites of crucifixion were complementary, not rival, the one located at the source of the masculine Church power, the ithyphallic St. Peter’s with its obelisks; the other in the Franciscan complex of St. Pietro in Montorio.

Francis was always marshalled on the feminine side of the church, and the Tempietto, affirms Clarke, is a female space6, a system of complex, tightly-nested interiors within crepuscular precincts, and damp inward-leading volutes; in effect, a formalised, classicised grotto, which in the Renaissance meant a generative space, a space where things transformed, came spontaneously into being.

And then, Clarke says, a single road leads from the Tempietto7 down the Janiculum to St. Peter’s Square and the great phallus. This road is, he says, a blood-hyphen written on the city, a ritual cursus of sacrifice and desire.

—ritual cursus—

– Map of Rome, 1652

Matthus Merian (with additions by Civ Clarke)

![]()

It is fair to say that this is not how I have experienced Rome, or the Vatican, or the Tempietto, on the few occasions I have visited them; nor for that matter does it resemble how I (nor, I strongly suspect, anyone, including and perhaps especially Bramante) experience space in general.

So in the interests both of refining and subduing Clarke’s reading of the Roman stones a little, I will notice that a hankering for Antiquity always represents a subconscious desire. Those stones and potsherds are suggestive of more coherent systems of thought lying beneath and behind us.

But this is an illusion. Wisdom has no roots; there is only more of the same (stones, pots, daggers) wherever you dig, and however deep you dig, until eventually the trail thins to nothing in the wastes of pre-history.

Even if Clarke and his sources are right, therefore, Bramante was building not a ritual cursus leading to Egyptian enlightenment, but a foolish rebus, a game of signs. There is no God, no martyrdom, no blood-hyphen, no order, no tapped ancient wisdom. Just this theatre for the puppetry of psychic objects, invisible to most Romans, then and now.

—foolish rebus—

– Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

Francesco Colonna

Having said that much, there remains the fact, if not of the path, then of a sequence of objects, a sequence more temporal than spatial: the Tempietto is followed by the Belvedere, by the plans for the obelisk, by the plans for St. Peter's, and so on, like so many stones thrown into the pond of Bramante's life, of Rome and its history.

The path or at any rate the idea of the path is a lure. The object of another's desire—Bramante’s desire, or Julius's desire, or Clarke's desire—if it is set at the end of tunnels, labyrinths, Egyptological paths, with their reverses, blind alleys, hidden alignments, will become, in treading the path, an object of your desire also8.

This is how we, neophytes in the arts of love, subject to the contagion of greatness, learn what it is we are supposed to want: Venus, Antiquity, martyrdom, abnegation, art, architecture, history. Or, indeed, unrequitedness.

But unlike following the path, clarifying the sequence can be a ritual of discrimination. The stones of Rome taken en masse are a mess of noisy data. Understanding sequences of precise objects is an exercise in quelling the noise, and seeing the structure.

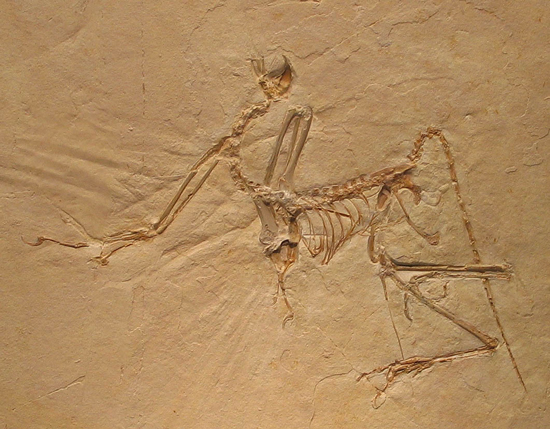

![]()

And so it is with our own desires, if they can be said to be properly our own. We find them buried deep in sedimented strata of miscellaneous other desire—whether learnt, borrowed, instinctual. They are compressed and malformed, barely visible, like fossils in twisted sandstone courses.

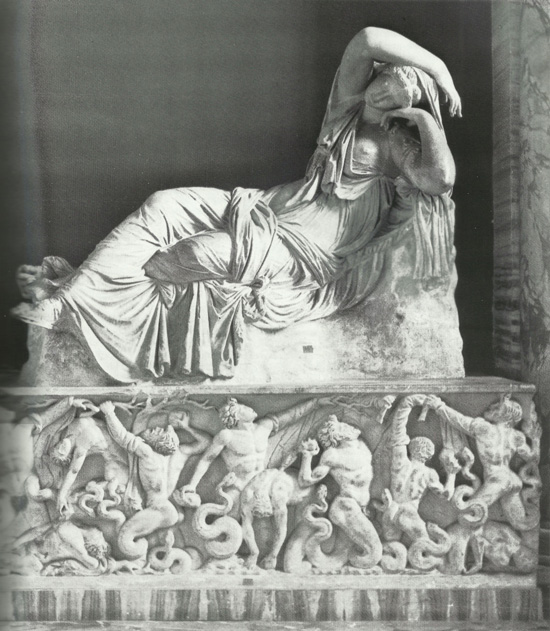

Whichever way you walked Bramante’s invisible linear city (in imagination), you would end by contemplating an emblem of skewed and compressed desire—the memorial to Peter on his upside down cross at one end, or the statue of Ariadne/Cleopatra, which Julius brought into the Belvedere at great expense9 just before his death, at the other.

—skewed—

– Crucifixion of St. Peter

Caravaggio

—compressed—

– Ariadne

The statue of Ariadne was set in a grottified niche and used as a fountain. For a long time it was identified as Cleopatra because of the asp bracelet on the figure’s upper arm. It is likely Julius accepted this identification, since it associated him still further with his great namesake, the first Julius, who had, so to speak, had the pleasure. It is now more generally accepted, however, to be a representation of Ariadne, mistress of the labyrinth, deserted by Theseus on Naxos and awaiting there the arrival of her crazy god.

—crazy god—

– Bacchus and Ariadne

Titian

Either way, it is a mourning, grieving, dying female, immobilised in stone. And what can a colossal stone statue or, for that matter, an empty stone mausoleum, represent but catastrophic absence? Here is nothing but stone, stone so heavy you could not, if you shouldered it till doomsday, shift it by so much as a nanometre. Like that great obelisk, it can be moved only with fabulous engines, straining sweating gangs of workers. Once you set it down, it will not be moved again for generations. No one has the energy. No one has the will.

In the same way, it is not Isobel Easter’s impending (and probably fictitious) return to Tony dell'Aquila's garden that is important. Isobel Easter’s absence, like Stone Ariadne’s presence, is an event horizon beyond which desire is sucked irrevocably, silently, invisibly. No information is returned.

This is the nature of all desire. Energy is torn from us and not returned. Or rather, what is returned, if anything, and only if we are lucky, is someone else's desire. And if we are unsure about our own, what can we know about the springs of someone else's desire, uncertain, as they are, of provenance and attribution?

![]()

You can love something—someone—without desiring it; and you can desire someone—something—without loving her. And love and desire can also coincide. You have to discriminate, and discrimination is alogical: is a function of experience, like that of a palaeontologist or fossil-hunter, who can project familiar lineaments in the dust, tapping and lightly scraping with her pick as though it were a form of thinking, tracing precisely differentiated lines between once living creature and dead earth.

It will not be some huge grappling full-formed Laocoön of desire that explodes from the ground into the light, pure white and dazzling for the satisfaction of popes. It will be hints and suggestions, a smashed half-forgotten mosaic of bones and desire which future generations will forget in the corners of unvisited museums.

—smashed mosaic—

– Archaeopteryx bavarica

Paläontologisches Museum

Still. I look at dell'Aquila and he seems happy enough, varnishing his wooden deck in the weak sun. He has been alive in the world long enough to know that universal fulfilment—the dropping of all the pins of desire and love into place, such that the universe unlocks like a puzzle, with no pieces over—is an impossibility. It is not a matter of improbability, or complexity, but of incompatibility: the solution to desire is not fulfilment, since the object you want and the object you get are not one and the same object. In the act of grasping, the world transforms.

So dell’Aquila conducts his rites of purification in his solar temple, and Clarke and I sweep the precincts, three puzzled old men each on his upside-down cross, learning that unrequited desire is not a failed object, not a degraded form of ideal, that is, requited, desire; rather, it inheres in every cell, every biomass, of Adam's whole Garden, a field of energy that just occasionally, just here and there, knots itself into a graspable object: the beloved.

—in the act of grasping, the world transforms—

– Apollo and Daphne

Antonio del Pollaiuolo