Taxonomical

—opened up to science—

– display of birds in the Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt

Norbiton: Ideal City is a binomial place: a place opened up to science.

But whether the generic name be Norbiton and the specific epithet Ideal, or the reverse—whether, in other words, Norbiton be one of a class of Ideal Cities, or the Ideal City one of a class of Norbitons— is not susceptible to logic.

Norbiton is an elusive creature, a shy scuttling phenomenon of the urban forest. It goes its own way. To capture it, pin it down, study it, trace its antecedents and family resemblances, its morphological distinctness, and in the end, to name it, has proved a labour of dizzying, entomological proportions.

And a city, once you have it spatchcocked in your specimen cabinet, turns out to be a singular object. It can be broken down into a range of familial characteristics, but, assembled, and named, it will sprawl stubbornly across an ever-extending range of categories, as for instance, those that are:

- called Norbiton

- Failed

- on a Hill

- Open

- Periglacial

- Lost

- Invisible

- Sacked

- of God

- as depicted in art, from a distance

- as depicted in art, from within

- Ideal

- Chinese

- & etc.;

We can at best give our object a name, a name that will loosely point to some shared Idea, some Norbiton, as it flutters by; a name which will allow us to consider it, together, in its various metamorphic states.

But to repeat: that initial naming will be, not a product of analysis, but an act of conjuration.

![]()

Everyone, whether they know it or not, has seen the photographs of Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov chasing butterflies. They are everywhere, fluttering and settling over the internet like a constant rolling migration of the blues which he described in Pnin1.

Nabokov made a serious study of butterflies, was for a time in the 1940s de facto curator of butterflies at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology; in various institutions around the world they still reverentially carry trays of butterflies prepared by the hand of the master, and value his taxonomic work, which included naming the Karner blue as a separate species and theorising wave arrivals of the Polyommatus blues from Asia to North America, a theory which in the light of more recent genetic sequencing look likely to have been correct.

—correct—

– Karner Blue (Lycaeides melissa samuelis)

By USGS Native Bee Inventory and Monitoring Laboratory [Public domain or CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Nabokov was a completist. In a 1970 interview, when asked what, if anything, he hated, he included in an appropriately detailed list “concise” dictionaries, and “abridged” manuals. But he was also a double exile (from Russia in 1919, and then from Europe in 1940), and a nostalgist. His art—whether of literature or of lepidopterology—represented a sifting of phenomena for their genealogical connection with his lost, pre-Revolutionary childhood, the childhood of a privileged boy in "knickerbockers and sailor cap", chasing butterflies. The Revolution was his metamorphic event; ever after, like a mature butterfly recalling the digested caterpillar, Nabokov acted and wrote as though he might reconstitute for a moment—always in memory—that whole lost creature, that child, poring over the pages of butterfly books in the long Russian winter, dreaming of the short season of warmth and flight.

![]()

I found it and I named it, being versed

in taxonomic Latin; thus became

godfather to an insect and its first

describer — and I want no other fame.

Vladimir Nabokov, On Discovering a Butterfly (1943)

![]()

Taxonomy not only brackets its objects for the convenience of nostalgic novelists: it also distinguishes them. It holds them apart. Thing bleeds not into thing. The variability of the cosmos becomes not only manageable, but clear2. Each object is hived off, held in the pool of a microscope’s light; one eye closed. And the taxonomical mind does all this, in the first instance, by accurately naming.

From the 1730s Carl Linnaeus set about new-modelling the settled but sprawly nomenclature of the World. His goal was in the first instance not to understand, but rather to name the objects of the cosmos unambiguously. His was a growing, commercial, intertrafficked world, one rapidly acquiring new objects of scientific enquiry, and it required an appropriate bureaucracy. If he, in Sweden, could refer to a plant with sufficient clarity that a correspondent in London, or Paris, or Cape Town, or Surinam, might call to the mind’s eye the precise plant intended, then the international network of rational enquiry would gain in rapidity and accuracy of transmission. To name well is to take a grip on the fuzziness of the world and its arcane interactions.

—take a grip on the fuzziness of the world—

– Adam Naming the Beasts

William Blake

But Linnaeus unwittingly had between his teeth a rich philosophical nut, a nut he would spend the rest of his life chewing on3. Taxonomical categories, he was to discover, can be said to represent the Ideas of the phenomenal world. In establishing a category, you allow individual instances to refine the category, as much as the reverse. The intertraffic which Linnaeus had pictured, would now play over an unexpected threshold: that between what is (the object) and what is not (the name, the category). The category allows us to pick up and rotate and inspect the instance; the instance, in return, allows us better to inspect our ideas.

Linnaeus had stumbled into a Platonic realm.

![]()

We, on the other hand, have stumbled out of one. Clarke, Emmet Lloyd and I are walking in Richmond Park. Richmond Park is contiguous to, but is not, Norbiton. In Norbiton there are paths, paths which bifurcate and converge and simultaneously describe the city and our experience of it. But we have roved off that map.

We have been drinking in the Albert on the corner of Queen’s Road and Kingston Hill, a winter lunchtime around Christmas, and now Clarke wants to walk off his beer, as he puts it; he is going out again tonight, and lunchtime drinking and evening drinking are distinct creatures, what drinking lies between them a soggy, dismal, mixed pleasure at best. So, on this preternaturally mild winter afternoon, we walk up Queen’s Road and into Richmond Park at the Kingston Gate, and then follow the fork which leads up Dark Hill.

A park—Richmond Park—is a wide-open space; a space criss-crossed with paths, perhaps, but one where the paths are habits easily broken. Within its ample and safe compass you are comparatively free to roam.

We strike therefore off the path and head for a tree which stands prominent on a ridge.

Clarke wheezes up the mild slope until at a certain point he says that he needs to pee. And so we veer again, this time for a fallen tree. As we approach, the ground grows boggy. This is a winter hill: in winter the water wells up from the land, as though in the weakened gravity of the sun the land had slipped a quarter-inch and the waters which underlie the earth were all seeping through matted vegetation.

As Lloyd and I stand and watch Clarke lumber toward the purely nominal privacy of a fat branch, the brown water creeps up over our boots; if we stand here long enough, I tell Lloyd, in this warm soup, the flesh and bones of our feet will spiral away in strands of vegetative matter, tendrils of undistinguished DNA; we will in short order be loose-wired to all of sludgy creation, and lost to ourselves.

But Clarke finishes peeing before Lloyd can properly digest what I am telling him, and we are free to separate ourselves and move on and up to the solitary tree.

We cannot identify it. It is at the best of times an effort for me to distinguish trees, one from the other. I need to see a leaf to have a chance: oak or ash or chestnut; or, more of a punt, hornbeam or alder or service. Underneath the leaves it is just all wood, so much interchangeable root, bole, branch, twig. I might as soon know an animal from a scrap of cartilage and bone.

—interchangeable root, bole, branch, twig—

– Development of the Bauplan

Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt

Emmet Lloyd should know better than me. He works in a nursery, plants are his business. But without his database, his barcodes and barcode scanner, he, like me, is helpless.

Clarke, wondering, lays his hand against the trunk and murmurs meditatively, animule, vegtebule, minerule.

![]()

The business of taxonomy is both to name—to attach free-floating objects (a butterfly, a flower, a moss, a proboscoid odd-toed ungulate, a primate, a tree) to names fixed in the superlunary realm of Academic Latin—and in so naming, to locate.

And as though alive to the fact that he himself, Carl Linnaeus, was a taxonomical object of enquiry, and ever the completist, the Swede swept himself up into his own system, docketing himself with the Latin binomial Karolus Linnæus. Thus, we assume, he came to know himself more exactly, and to a lesser degree of variance.

Taxonomical names have an interlaced precision: they should be handled deftly, with sensitivity. This, for example, is how Nabokov knew his butterflies. And it is how we know ourselves, in sum. We have our taxonomical personalities, the names and identities registered in the census, in the map of births and deaths; we are a part of the statistical understanding of our time, in numerous ways we will conform to a pattern.

Common names, by contrast, are used by people who know the plant or the animal in question, who know its habits and its habitats. By what name, we might wonder, did Linnaeus's wife know him? And his parents, when he was a child?4 Little Karl, toddling around, what nicknames did he grow into and out of, stored up like a history of himself, concealed from him in the pre-history of his infancy or recalled like the names of forgotten friends? Our names are legion, mutable, circling their objects—their taxonomical barycentres—in eccentric orbits, adumbrating highly particular individuals, at particular moments, past, or passing: a genealogy of species.

![]()

Linnaeus's practice was in keeping with the long if by now dying tradition of humanist scholars and Renaissance magi going by Latin appellations5.

But there were exceptions. The English botanist John Ray (1627 - 1705), the first to give biological definition to the term species and an early theorist of sex in plants, renamed himself Ray from Wray when he understood that this was the age-old practice of his family. Precision, for Ray, or I suppose Wray, lay not in distinguishing, but in connecting: in placing himself on a genealogical tree.

Bifurcation is a fundamental tool of the mind. We observe that things divide as they progress or grow: the branches of trees, the channels of great rivers, the blood vessels, artery and vein, road and path; families have their collateral branches, religions their schisms, ideas their antitheses. The whole world bifurcates.

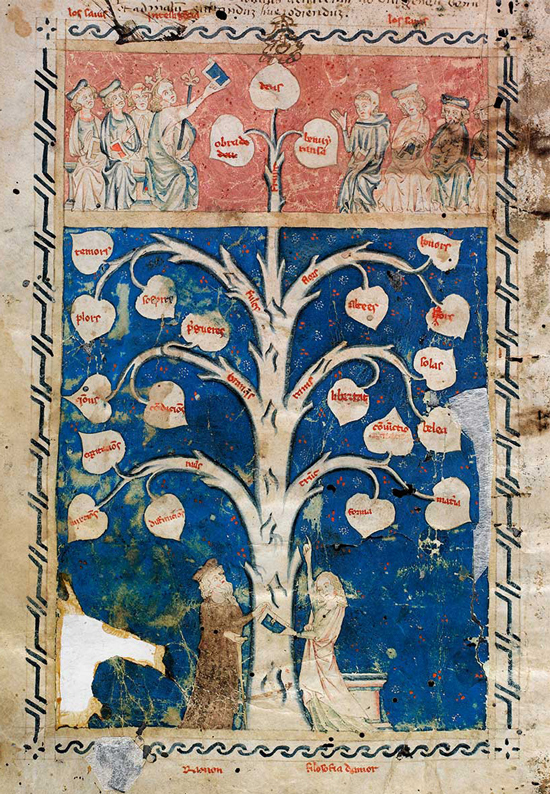

But bifurcation suggests also another, antithetical possibility: convergence, a common origin. It suggests that you can read your tree backwards, from the tip of the branches down; or trace your capillaries up by vein to the dark beating heart of the matter. Thus for the Catalan philosopher Ramon Llull (1232-1316), all knowledge of the cosmos could be not only laid out on the page like a tree, or held in the mind like a tree, but also climbed like a tree.

—climbed like a tree—

– Arbor Scientiae (1295) of Ramon Llull

Llull's God sits at the arboreal crown, like a fairy at Christmas; the roots (added in subsequent iterations of the arbor scientiae) represent the various emotions and drives, the moral structure upon which you must draw if you are to ascend securely; if the whole burgeoning cosmos of your mind is not to topple over under the weight of its own grandiloquent vision.

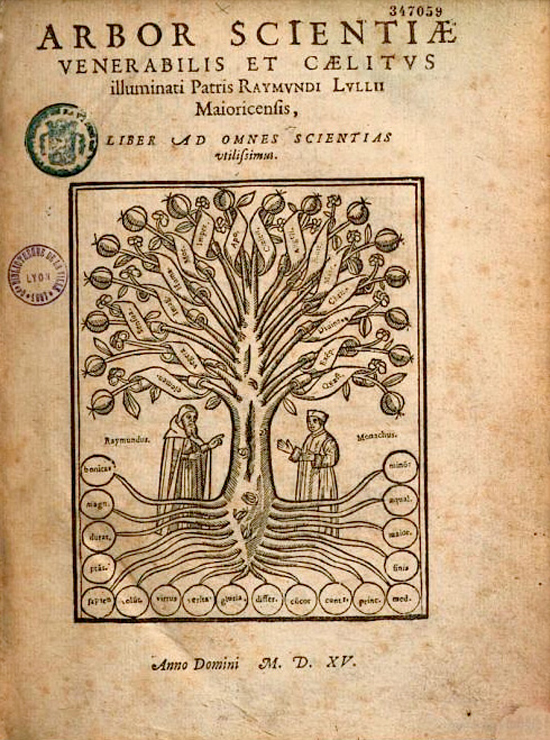

—climbed like a tree—

– Arbor Scientiae (edition of 1515) of Ramon Llull

The moment you break knowledge up into discrete elements you imply bifurcation, nesting, articulation; you allow for movement between objects. So for Llull and his followers, to know was to move.

The Cosmos, you would come to see in the course of your ascent, did not dangle unhung from the sky like Aquinas’s silver chain; it was rooted in a place and proliferated down, and out, to where we, in the darkness or the light, at the tip or root of it all (a pardonable confusion, in the circumstances) sustained by leaf or burrowing rhizoid the whole radiating complex of creation.

The tree of knowledge was a literal structure, if by tree you understood something skeletal, a necessary patterning of nature, rather than something contingent, living, hence patterned6. There it stood, not a litter of possible elements but a graspable, if chimerical, whole, as though you might ascend an alphabet.

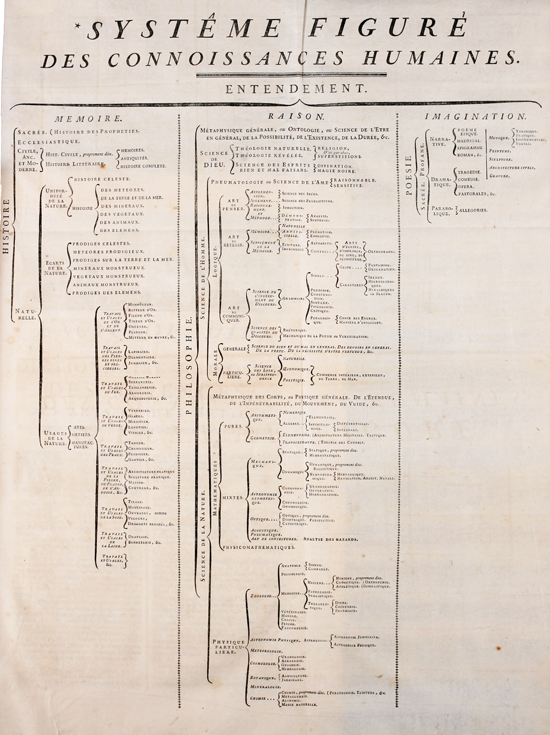

And while, by the time of Linnaeus and the Encyclopédie, the tree of knowledge would be deracinated, all knowledge still available, still interconnected, but isolated for examination in a pool of light; nevertheless, the tree retained its coy challenge: climb me.

—climb me—

– Figurative System of the Organisation of Human Knowledge

Encyclopédie (1752)

![]()

In the same way, microcosmically, we know that our psychic worlds are peopled by various species: fear, for example, or apprehension, or the night terrors; or love, affection, obsession; so many taxa which will themselves be refined, conflated, split over time as they are read against actual instances and occurrences.

Or, if we prefer to proceed not rationally but empirically, we can individuate specific reactions to specific events and by a reading and parsing of pattern and variation we can build up a database which will show how, theoretically and over time, our emotional and intellectual and behavioural responses trace up to common origins, small furtive proto-placental mammalia of psychological damage and trauma swollen now in the absence of scaly thunderous monstrous stalking parents and teachers and assorted authority figures to dominant species, ecological vermin, the rodential destroyers of worlds.

![]()

A keen eye can presumably read the signature of a tree—an actual tree, such as the one Clarke and Lloyd and I are standing under—in the pattern and frequency and nature of its bifurcations. The bifurcating habits of a tree are specific qualities.

At some point in the 1620s the keen-eyed painter Pieter Saenredam had bifurcation and specificity on his mind. A sheet drawn in pen and ink and wash, and dated 1617 and 1625, shows two bare trees, and two views of towns.

—bifurcation and specificity—

– Profile Views of Leiden and Haarlem and Two Trees

Pieter Saenredam

The towns are Leyden and Haarlem, this we know from the tiny precise writing above them; there is a flourish of the pen above the town of Haarlem, as if the repetitious self-same code of the writing were suddenly spinning out a new species, an incorrigible will to draw, to shape, to illustrate; as though Haarlem could be designated better by a highly specific dynamism of the pen than by any conventional lettering.

Or, indeed, better designated by a profile skyline. Netherlandish art is full of views of towns, mostly generic. In the fifteenth century no group of saints, no iteration of holy writ, was complete without its miniature townscape, its fantasy Burgundian castle, punctuating, perhaps identifying and signing, the land. There is an impulse to locate events against a civic context. This happened, beyond the walls, there. But which walls is not relevant. The relation—town to country, heaven to earth—is what counts. The existential categories are broad.

By the seventeenth century, Dutch artists, the inheritors of those early Netherlandish miniaturists, were paying closer attention to the actual configuration of the world. Taxonomy, the assigning of individual instances to characteristic and interrelated groups, must begin with a firm identification of the individual phenomenon and its structure; its generative code is implied in the actualisation.

Thus Vermeer painted Delft as though it were swimming under a microscope; Ruisdael recorded towns like calciferous encrustations of species of coral, hard stone growths in the soft land.

—hard stone growths—

– View of Haarlem with the Bleaching Fields (Mauritshuis, The Hague)

Jacob van Ruisdael

Saenredam too, seems to be reading his little town profiles as precise and characteristic bifurcations of the ideal impulse of town; Leyden and Haarlem belong to the genus "town", species "Dutch town", or "prosperous town"; town spirals away from town in a system of bifurcating streets and citizens and economies and histories; no town can follow any other; each has its own coded pattern of growth. They will continue to proliferate in ways which are characteristically and unconfuseably Leyden, or Haarlem. A tree does not grow into another tree; a town does not grow into another town.

![]()

Except when it does. Norbiton would once have been a farmstead7, a discrete object of civic knowledge. But it is long since sucked under the tow of the Great City.

I would turn my head now, if I could, and see, laid out beneath us with its characteristic profile of roofs and gables and towers and spires, here in the midst of this little Dutch-like economy of managed land, the Ideal, Open, Periglacial, Invisible Failed City on a Hill, complete and prosperous burgh, my Norbiton.

But Norbiton is harder to read than that. Even if we start from the premise that all cities are in some sense ideal—each city a name or gazetteer of names (streets, citizens, institutions, shops, schools) to which loosely and shiftingly attach the myriad of overlapping perceptions and histories and stories of their inhabitants and visitors and historians and geographers8—Norbiton does not so much clearly instantiate itself, as precipitate slowly from a salt sea of town-elements, which we call, for convenience, London.

![]()

Towns and trees were rhymed for Saenredam also in the paintings for which he is best known: his sepulchral white church interiors with their colossal arborescent columns.

—arborescent—

– Interior of the Church of St. Bavo, Haarlem

Pieter Saenredam

The interior of a Dutch church is the innermost space of the public city. It is here, in the seventeenth century, that the community consults its own transience. Assembled at any given service, the citizens, scions of families bifurcated down the ages and resident here, represent one possible state of the city. In their shuffling arrangement in the nave we see a city always on the very the brink of extinction and reconfiguration. A city constantly rewriting itself in the register of births and deaths, here played out in metamorphic ritual in an edifice with a characteristic signature. Churches may bear a family resemblance one to another; but they are also particular each to its place. In the multiplication of sliced samples of the world which Dutch art, from one perspective, represents, Saenredam’s churches are so many readable sliced tree trunks, their rings speaking to a specific time and place, not to a generic structure.

—specific time and place—

– Assendelft Church, with gravestone of the painter's father in the foreground

Pieter Saenredam

![]()

Norbiton, too, is constantly re-writing itself in the register of births and deaths.

We stand up here, by our forlorn and patient tree, in the lurid light of a winter sunset. Low yellow light is working on the green-black bark of the tree, on the reflective, troubled dome of Clarke’s head. We do not talk much. We only look around. From here, the city—Great City, Ideal City, what you will—is invisible. Wiped from the earth, it might be, in an apocalypse of known forms.

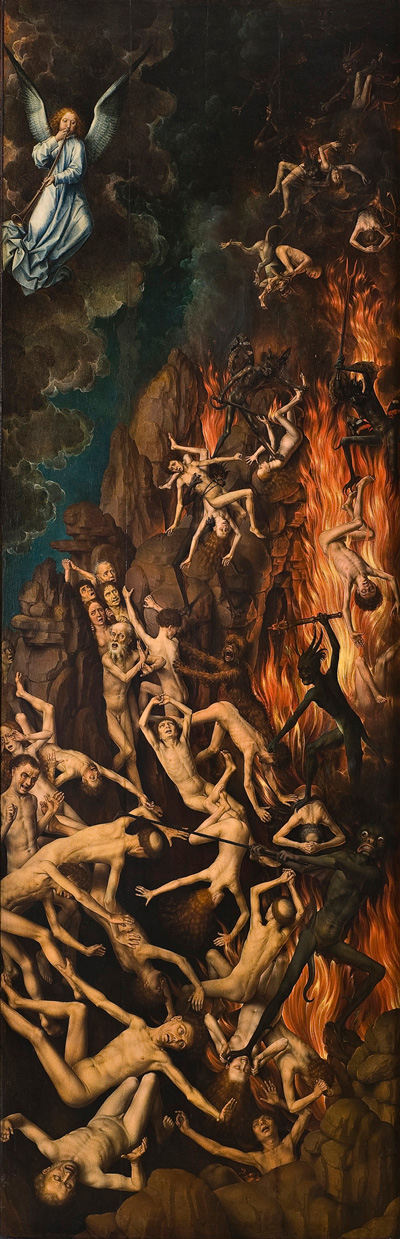

There is a painting in Danzig/Gdansk in Pomerania/Poland, a Last Judgement by Hans Memling, in which souls are weighing in the balance. On the horizon, where in other compositions a small city, a confabulation of turrets, might be expected, there is nothing; only more horizon, a field full of folk, of spiritual wheat and chaff, sheep and goats, ones and zeros. Here, at the extreme end of history from Adam's naming of the creatures, all terrestrial taxa—nested hierarchies, branching institutions, all geographies, cities, trees—are now irrelevant.

—irrelevant—

– Last Judgement

Hans Memling

There is only one city now, the City of God, a place of ramparts and battlements, of civic order and unidirectional, unbifurcating streets, into which the elect are absorbed, fresh-clothed and docketed for salvation. The reprobate, meanwhile, are consigned to a wilderness, a self-similar omnidirectionality of fire and rock.

Non-existence also has its taxonomy.

—elect—

– Last Judgement

Hans Memling

—reprobate—

– Last Judgement

Hans Memling

Broad taxa are the least forgiving, the least escapable. Exist or do not. There is very little shading, very little in-between. Ghosts, perhaps; perhaps dryads; all those half-creatures of the imagination, the homunculi, the myriad foetal clusters of amniotic cells suspended, unlocated, so many miniature, gravely formal gestures towards life; all those sprites, artefacts, gods, ideal cities, fables, myths of childhood, the current memories of what was not and the lost memories of what was, the endless forking paths never walked or glimpsed, the infinite unreal contiguous lives never lived. All this, perhaps, but nothing substantial. No: exist or do not. There is nowhere to hide.

![]()

Trees and butterflies have common names—oaks and blues, ashes and red admirals—a serviceable oral system which indicates a known entity, draws on a shared experience.

Linnaean and, still more, phylogenetic taxonomies are by contrast a scriptural practice: phylogenetics works on the written DNA, the written and re-written code, traces the minute scribal error of our helical libraries9, our signatures, and pieces us—all of creation—back together, like a mosaic; we are all born of the same one primal filament, some wriggling proteinous ur-worm of chemicals, we are all derived from a trauma to the peace of insensate matter, a significant rent in non-existence.

Either way, we seek to grasp the world. Naming is an exercise in power. Oral traditions are mixes of spells, of incantation; the right flowers, plants, stems, roots in the known order will quiet a fever, purge a gut, bring luck or love; plants have their signatures, are written in the great spell book of the cosmos. Or in scientific naming we appropriate all objects of knowledge to our system, exercise our power by means of forceps and gloves, cleanly, from a distance.

But we seek power in this way, in our naming and re-naming of the objects of the world, not for the love of power, but to assuage our fear.

This is why we name and rename a child; we try to find the child's name before the child is born, try to feel it out (Karl, Karolus, Vladimir) then we winnow and shape the name with the child as the child grows (Micheau); we try to get a grip on this thing, this phenomenon; more especially, we try to get a grip on the emotional life which this child provokes in us; not merely anxiety, love, existential distress, proleptic sorrow; but unnameable orders of anxiety, variegated classes of love, ill-distinguished species and sub-species of existential distress, proleptic sorrow.

—proleptic sorrow—

– Virgin and Child

Giovanni Bellini

![]()

We are just gathering ourselves to quit our winter tree when Emmet Lloyd is suddenly struck with wonder. There, past his nose, flies a butterfly.

Clarke and I do not see it at once. Emmet Lloyd shouts something incoherent, non-specific, a generic shout of wonderment, and waves his arms at the world at large. But then we pick it up, first Clarke, then me: a small blue creature dabbing on the winter air—a mild winter, admittedly—doomed by the upcoming frosts, investigating this world anyway in its brief entanglement with light.

Emmet Lloyd, I have only recently discovered, is married with two children, a boy and a girl. Children represent homologous traits: they locate the individual more precisely in hominid space. Knowing Lloyd’s history, in other words, I have rapidly had to reclassify him, as a cladist might reclassify a whale or a bear, most notably as a citizen of the Ideal City. So I turn my attention back to him now as he watches the butterfly disappear down the hill.

Did he for a moment mistake Clarke and I for his own children? Has he internalised a drive to describe the detail of the world in its own singular terms, to point out whatever seems to be caught in the existential half-light between the specific and the general, as, with children, parents are wont to do?

Hard to say. His wonderment, if that is what it was, is inarticulate. He has nothing to say, no way to say it; he says only, butterfly! and smiles. And we nod, and head back down the hill, in the singular butterfly's wake.

![]()

Everyone dreams in his own way, in her own way, of disentangling the objects of the mind, holding them clearly in sight, seeing to which genus they belong, seeing whether they are the basis for action, inaction; seeing whether they qualify for attention, inattention.

We want to understand, not some underlying, unifying principle—after all, whatever we happen to have is merely a sample of how things happen to have turned out—but rather to place the objects of our attention in relation to one another.

And that whole relation changes with the advent of each new object. Each new object refines the categories to which it belongs: each individual object is not merely an instance but a new summation of all available categories. Each node in every figurative tree is a little original sin, which must be accounted, and may just be atoned, for in each actual thing in the world. Because for the thing in question, the singular thing, whatever that thing might be, there is no place on a branching tree; it is, rather, a moment of complete and sublime ignorance, of pure observation. There is just this one thing, in the world, just now; just this one thing happening.

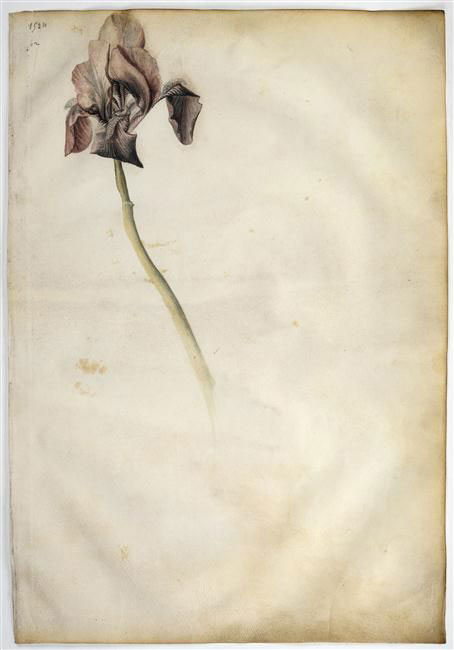

—just this one thing happening—

– Iris Reticulata c.1450

Jacopo Bellini