Mnemonic

—encode the dead—

– Tomb of Sixtus IV,

Antonio del Pollaiuolo

How can we best encode the dead?

The business of memory is mostly to forget. It proceeds by dereliction. It generalises and discards, leaving us only the indigestible teeth and jewellery, so to speak, of people or places or times we have known, so much disjunct cannibal ornament.

How then, can we best encode a living person, such that after their death and with the passage of time we are not left with a hotchpotch voodoo scarecrow, stitched together from ill-matched anecdote, floating in a vague non-landscape?

I am talking of the dead, but the dead are only a case study. To repeat my question in more general terms: how can we better encode a current set of variables, whether that set of variables be a person, an experience of love, a place, a time, a period in our lives, such that, at a later date, we can not only make useful enquiries of it, understand it better; but, on demand, to some limited extent, reconstitute it?

How can we in other words remember well?

![]()

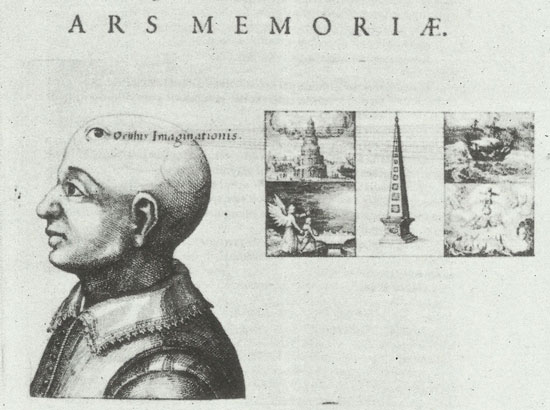

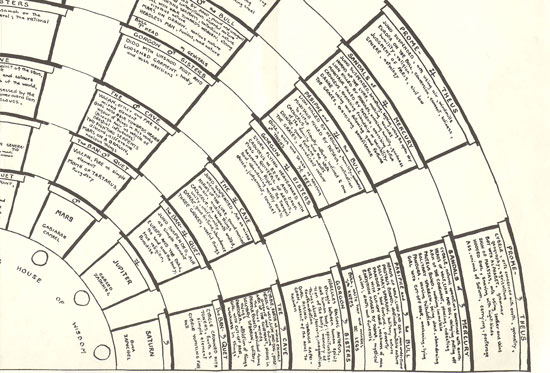

The well-ordered memory as described by classical rhetoricians is an imagined architectural space furnished with strange objects and incongruous tableaux.

—incongruous tableaux—

– Title Page of Ars Memoriae,

Robert Fludd

We are for instance to imagine that we are lawyers, tasked to recall that a man is accused of poisoning in order to gain an inheritance, and that there are many witnesses in the case; we should imagine the victim an invalid in bed, the accused standing before him holding a cup (the poison), tablets (the Will, or inheritance), and a pair of ram's testicles (testes = witnesses)1.

The real and mundane is represented by the arcane, the ludicrous, the peppery, the strange. And in this way the unmemorable—your life, your experience, the totality of all knowable objects—can, against the cosmic odds, be made to stick in the mind2.

![]()

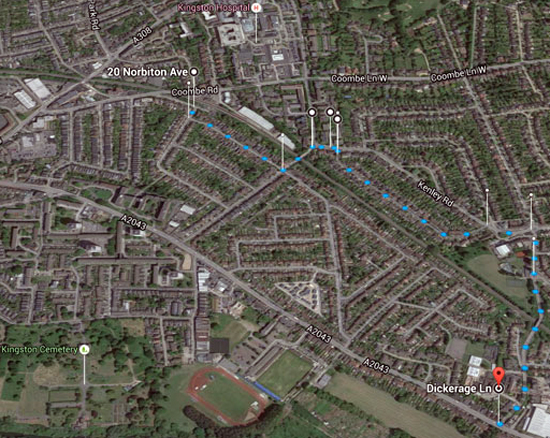

We complete our boundary walk of Norbiton: Ideal City some weeks after Hunter Sidney’s death.

This is no mere continuation of the first, aborted circumambulation. That was a foundation gesture; this is not. This is commemorative, and commemoration ravels time back up, for a spell. Thus our second route runs contrary to our first, and makes a retrograde (albeit clockwise) progress. Life, says the route we etch on to the map, does not go on.

Clarke in this connection relates that in Ancient Egypt the tombs of the early Pharaohs were laid out in labyrinthine form, a form translated in later dynasties to the mortuary temples which stood alongside the tombs and did much of their ritual work3.

Hunter Sidney, he implies, is still treading out his passage to the afterlife; our sombre sarabande or allemande up here on the surface of the earth, dancing across the outermost shell of Norbiton, criss-crosses our friend's own kinked path as it evolves somewhere down below.

Clarke is right. It is our clearly our subconscious hope that, in so crossing paths, we might generate an imperceptible but cosmically significant ampere of current, might yet keep our friend flickering for a few moments more in life of a sort; and thus by the operation of some bizarre cosmic physics at once aid his passage to the underworld and simultaneously, perhaps for our own sakes, retard it.

That Hunter Sidney would have scoffed at all that rich mysticism is irrelevant: ritual and communion with the dead mark out our purpose today, so we embrace it, the eternal entanglement of upper and lower, electron and proton, modern and ancient, Clarke and Sidney, Norbiton and Egypt, the quick and the dead. Here we are for all time: treading out the precincts and involutions of Norbiton: Mortuary Temple.

—Norbiton: Mortuary Temple—

![]()

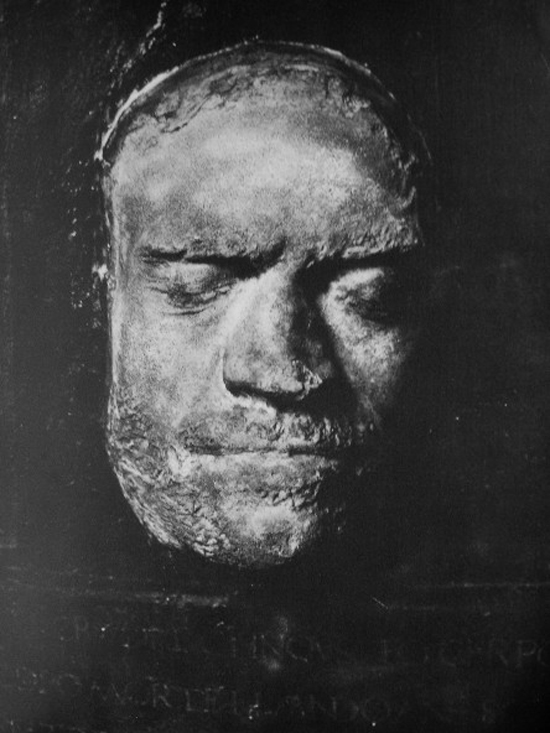

I recall, perhaps imprecisely, that in the room of quattrocento sculpture in the Louvre, lined up with the portrait busts of Filippo Strozzi and Dietisalvi Neroni and the rest, there is an odd relic of Florentine interior design: a terracotta death mask of a woman in a scalloped decorative niche (perhaps Battista Sforza, perhaps not).

—Florentine interior design—

It is a rare survival. From a remark by Vasari, it seems that Florentine palazzi were filled with such objects, typically set high-up over doorways, cornices and windows, not unlike the elevated portrait elements on tombs in Florentine churches. You would glance up and see the illustrious dead of the family not only commemorated but virtually present, contributing to the weight and consequence of a family’s current estate.

The placement of the Louvre death mask among the portrait busts is not accidental. A death mask is a portrait made without the agency of human hands, and vouchsafes a quasi-miraculous transmission of detail4. Even to us they have something of the photographic about them, a greater fidelity than the intervention of human sensibilities can guarantee, as here for instance, in the death masks of Lorenzo de’Medici and Brunelleschi:

—Lorenzo de'Medici—

—Brunelleschi—

Conversely, Florentine portrait busts, while often done from the life, were frequently also done from the death, using death masks as sketches. The death mask is a portrait bust in the raw, it guarantees a certain verisimilitude. These are no longer mere objects of stone, but real, petrified humans.

—petrified—

– Portrait Bust of Niccolò Strozzi,

Mino da Fiesole

![]()

For all that his house was a vivid mausoleum, it is unlikely that the Florentine grandee going about his business took much notice. His furniture—for all we know, like his memory5—was a formal and functional system, not a source of anxiety and regret.

And this is true also for us. Your own house, while it is most likely supplied with a useful sub-structure of rooms, furniture, and incongruous knick-knacks, makes for a poor memory palace.

We move through it as through a palace of forgetfulness, and regard its ever-shifting multiple surfaces of dishes unwashed, clothes unlaundered, dust undisturbed, its cyclical litter and toil, its scurvy tide line of unmemorable endeavour, with unseeing eyes.

But this is not the case in someone else's house. The burglar or the cat-sitter will confirm the paradox that a house stripped of its genius loci, its owner or customary inhabitant, while it may be inert, is nonetheless curious, memorable, spectral; the objects left lying around seem purposefully, even symbolically rooted, subject to a double-gravity, a thrilling, petrified object of memory.

![]()

We are set to do a little zig-zagging today, crossing and recrossing the northern Norbiton threshold. We will pass in by the station, then out, then in again, crossing the railway each time, first under, then over, then over again.

But first we will take a coffee at Neville's station coffee shack.

—rituals—

The station entrance is a thicket of gates and fences, there are rituals of touching in and touching out to be observed; but these apotropaic gestures relate to an axis of movement (i.e. getting on a train) wholly discontinuous with our own; so we just stand on the platform and drink our coffee unmolested in the mild and slanting equinoctial sunshine, dispose of the paper cups and their plastic lids, nod to Neville, and begin to walk.

We are five: Clarke, Veronica di Viggiani, Solomon, Emmet Lloyd and me. Solomon was not with us on our first circumambulation. Neither was Veronica. They take the place of Hunter Sidney, of course, and of Kelley, whom we did not think it appropriate to invite.

![]()

I have been spending a lot of time in Hunter Sidney's house. Veronica de Viggiani, his friend and confidante, with whom I shared his death watch, is staying at the house, hanging on. And we are conducting a love affair in it.

For some weeks we have been gliding between Hunter Sidney’s belongings, leaving them for the most part untouched, as though they were totems of an actual memory palace. It is our mnemonic refuge.

In 1558 Pieter Bruegel produced a drawing, subsequently realised as an engraving by Pieter van der Heyden6, of Everyman, or (Elck). Like a quattrocento Jesus, Everyman is doubled and redoubled across the insane narrative, searching, like senility in an attic, for he knows not what.

—he knows not what—

– Elck,

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

It is a memorable image. The objects which he inspects and by which he is surrounded—a lantern lit in the day (emblem of folly), cards and chessboards, sieves, scales, an orbis terrarum cracked like an egg, another lantern, again the lantern—tell him nothing useful, relinquish nothing of value. He returns to them over and over, it is not a search but a reflex searching. Properly inventoried, this pile might make a good mnemonic system; as it is, it is like the rubble of some memory place, a Ciceronian dementia made visible.

—Ciceronian dementia—

– Elck,

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, engraved Pieter van der Heyden

In time, Everyman’s inspecting will become sifting, sifting will become sorting; these defunct objects will take on associative meaning, will find their use and their place. His search will yield a pattern of sorts. It is inevitable.

Just so, Veronica and I, as we move around in Hunter Sidney's inert house, start to generate a little gravitational flow of our own. We use dishes and wash them up, find corkscrews and glasses, water orchids, puff cushions. And we know that in time all of this will be woven into the broader patterns of our life, normal space-time will reassert itself.

It is as if the handling and the use and the arrangement of familiar objects on the one hand, and the workings of the memory on the other, are linked. And Veronica and I have stumbled into a neutral space, spared for a time this sifting, sorting, this truck with objects; we are dissociated from the current and flow of our own life, hence from memory, hence from the knowledge of consequence. We are cut off from the past and touch only lightly on the present. No wonder we seem to ourselves to be in love.

![]()

Classical and medieval memory was conceived of as an ambulatory space in which direction was immaterial. Once the order was fixed, information could be read off both ways without any ramping of difficulty.

Thus the elder Seneca could repeat two hundred lines of verse that had been given to him at random by his students either backwards or forwards—it made no difference to him once he had them properly stored.

He could not, however, marshal all his information simultaneously; he could not compare like with like and make intuitive leaps and connections, except against the grain of his system.

And this was a limitation. The memory, after all, was not merely a handmaid of rhetorical delivery: it was the seat of invention.

Thus it was that Giulio Camillo Delminio (c.1480 -1544) built his once-celebrated, now-forgotten, memory theatre.

—now-forgotten memory theatre—

– section of the theatre, reconstructed by Francis Yates

Camillo was a conventionally bumbling magus—he spoke Latin very poorly, and stammered, and he must have been very fat since a story is related of a visit he paid to a menagerie in Paris in the company of the Cardinal of Lorraine during which a lion escaped, and everyone ran away except Camillo, who stood rooted to the spot 'because of the weight of his body which made him slower in his movements that the others'7.

He was, however, immensely famous in his life time and for a while after his death, on account of his extraordinary Theatre. It is not very clear whether the memory theatre was an actual structure you could enter, and if so what it looked like—descriptions vary from a building in the form of a classical amphitheatre to an elaborate chest-of-drawers; but either way, great quantities of knowledge of every sort were visible at a glance and centrally organised around a complex mnemonic scheme radiating from a conflation of the Sephiroth, the Pillars of Wisdom, and the Planets.

The knowledge was visible at a glance because it was represented not in words but in peculiar and memorable images.

The image, and in particular the hieroglyphic, was to the sixteenth century nearer to the truth of what it represented than any description. Thus the theatre not only showed you where any given bit of knowledge was and how it related to all knowledge in the cosmos; but actually showed you that bit of knowledge. The order and its representation were proper to one another: the one was, in a sense, the other. To memorise was to understand. To see with the mind’s eye (once this vast structure had been internalised, digested) was really to see.

![]()

And yet the theatre remained a shabby material object animated only by the yearning of its creator. Every magus must sooner or later accept that the world does not conform to his knowledge or alter to his spells. Camillo’s system of universal knowledge, memory and understanding was mumbo-jumbo. It might fool the King of France, but it would not fool the cosmos.

Camillo spent his life working on it, tinkering with the arrangement of its little drawers, always promising its completion, and the completion of a book that would lay out its operations. But the theatre was never perfected, never fully laid out to Camillo’s satisfaction; the book was never written. Just a few years after his death the theatre was a thing of legend—had it ever existed? Camillo rapidly became an object of ridicule, his theatre, his ramshackle splintery prototype of universal data storage, a mirage constructed by a mountebank; and then both were utterly forgotten.

![]()

To be sure, we know our way around knowledge and memory better than Camillo.

We know for example that knowledge is a network, that it has its nodes which are variously connected, and that it is the number and variety of connections which is interesting, not their static location.

We represent our knowledge accordingly, and our memory theatres encode networks, not taxonomies.

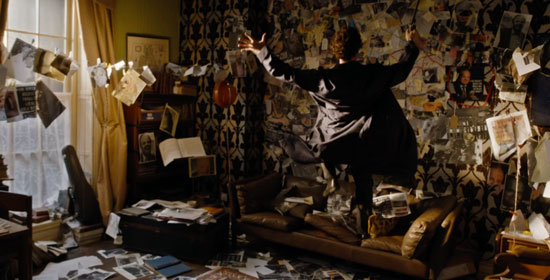

Thus our paradigm of knowledge and understanding is not a Roman or Palladian theatre, but an incident board.

—incident board—

– Now You See Me 2

To map and understand human activity is to construct a spidergraph, a genealogy of crime. We sit and look, and each picture concentrates our knowledge of a given node. Like an orator, we could if we wished expand each node extempore (and actors in detective shows occasionally do), but we do not need to, because we understand the interconnectedness at a glance, we see the connections immediately.

—at a glance—

– Rules of Engagement

The beauty of the incident board and its cognates is that we can and must move pictures or visual objects around, we can and must annotate, the better to model the growth of our knowledge, its beard-scratching mobility.

At the point where the truth behind an incident board is sufficiently well known that, say, a prosecution holds water, the agent of detection—the detective, the writer, the actor—dismantles it, takes down the photographs, files them away out of sight and out of mind.

The photographs on the wall were never a representation of the facts; they were a contemplative field, an aid to meditation. They represented not what we knew, but how we were thinking about what we thought we knew.

—how we were thinking—

– Sherlock Season 4 episode 2

![]()

To strike and follow the boundary of Norbiton we must first dip under the railway tracks by means of the subway.

—subway—

In certain seasons the subway is ankle deep in waters. Not today. We emerge, powers of recollection undiluted, on the far side of the station, where Norbiton Avenue kinks into Norbiton proper. Just beyond the day nursery, the little play-limbo, we see looming before us the towers of the Cambridge Estate, smoking (figuratively, but also for Clarke, in memory) and Tartarean.

We enter Homersham Road. Homersham Road is not a road. None of these 'roads' are roads. They are streets. Roads are thoroughfares: step into a road and you are swept along with migrating whales, off to cold and dark arctic seas. Streets are mere stacks of residence, the open shelving of the civic data-retrieval system, people and cars stored here in semi-stasis.

But on Homersham Road we are nevertheless worming our way inside the body of Norbiton. The road [sic] is lined with small municipal trees. Clarke relates that the streets of certain Mediterranean towns are similarly lined, but with citrus trees. You could if you wished pluck an orange as you strolled. But this is Norbiton: Mortuary Temple; nothing grows here that was not planned and brought and planted by the council; there is no volition of nature.

Homersham Road leads to Gloucester Road where again we turn left, over the railway bridge and out of Norbiton. A representation of a roundabout in brilliant white paint impels us on our vorticose path down Kenley Road.

On Kenley Road we pass the entrance to the dead-end of Lambourne Grove, and immediately dip into Orme Road. Orme Road stays closer to the railway line, invisible but controlling away to our right.

Orme Road is a bewilderment of half-timber. Mock Tudor, in its zany conservatism, characterises the street, but generalises the houses. There is, however, a progression: at the Kenley Road/Gloucester Road end the half-timbering is only suggested, a mere inclination to half-timber; as you make your increasingly epileptic progress down the street the black-and-white timbering proliferates, spreads, dominates; by the end, a sort of spectral phase-locking has occurred: all is a rhythmic humming juddering resonant patterning; timber echoes timber in harmonious, if unreadable, hieroglyph; if Hunter Sidney is passing beneath us at this moment, we surmise, his passage will have been cosmically smoothed and accelerated.

—spectral phase-locking—

![]()

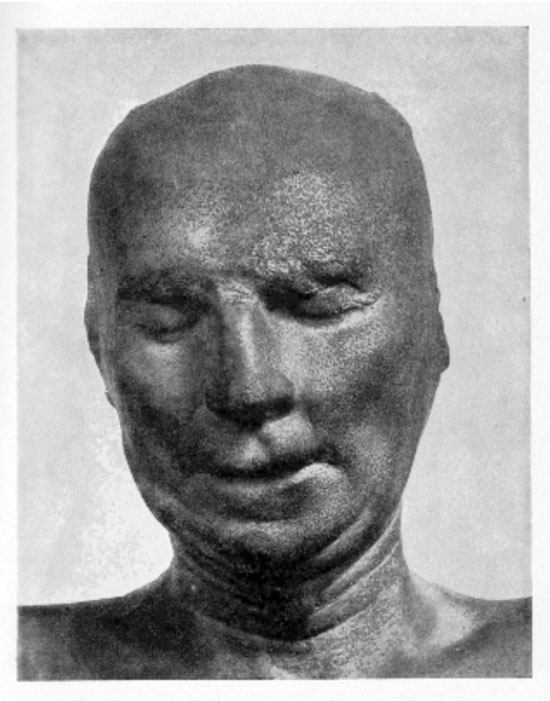

If anyone knows how to unperplex the crooked paths of death, it is Hunter Sidney. Unriddling was, after all, his life’s work.

Hunter Sidney was a writer, or more precisely an administrator, of a meta-detective novel buried in the deep net which he knew as the Love Filter (see Bureaucratic starting roughly here). He once told me that he had a map of it, but never showed me that map.

After his death I discovered that it was not a map at all but an incident board, or a miniature memory palace, located in one of the rooms on the first floor of his house.

The artefact ran along three sides of the room. There were cork boards densely pinned with sheets and half-sheets and scraps of paper, both printed and hand-written, matted in deep layers which entirely obscured the bottommost sheets.

Black marker pen zoned off the boards into irregular provinces. There was evidence of colour-coding, spot stickers of different colours with numbers written in them in biro, and variegated post-it notes, festoons of ribbons and twine of different colours interlinking the various elements, as though the structure of the work were its ornamentation, its decorative element.

Here and there on the wall Hunter Sidney had stapled printed images, in various categories of my own derivation, as follows:

animals extant (dolphin, leopard, greyhound, fluttering blackbird, elephant) imaginary (minotaur, cyclops, mystic lamb, beast of El-Adrel IV) and extinct (auroch, glytodon, megatherium)

places real (Venice, Jerusalem, etc.) and imagined (Dis, Jericho, Norbiton)

photographs of people living (Viv Richards, Monty Don, Roy Hodgson) and mostly dead (Francis I of France, Scott of the Antarctic, Gene Kelly, Pope Pius II)

objects useful (spade, lamp), and less useful (a lyre, a sextant, backgammon board, winged helmet, a loom)

Some of these images were part-smothered by layers of sheets of paper, pinned in place I suppose by events; others not obviously bound into the system of ribbons and pins, but able to move freely over the strange surface of their world.

Other than the boards, there was a table under the window on the fourth wall, one swivel chair with steel castors, and on the table an Anglepoise lamp. There was no computer; this was an analogue space.

In the days leading up to Hunter Sidney's death and at his request, Veronica de Viggiani had started to dismantle the room. The Love Filter was her inheritance and she would need all this material. Her vision was to start by reconstructing it at her own home in Italy, and to this end she had taken dozens of photographs, and was removing the various elements layer by layer, like an anatomist or restorer, and placing them in cardboard boxes she had bought for the purpose.

It was slow going for her. She been contributing to The Love Filter for almost as long as Hunter Sidney, so peeling back the layers was like reading back through twenty years of her own life, prismatically. She would stop and read for hours as she went; uncover buried photographs of characters long dead, subterranean ribbons which she would trace in their obscurity around the room, noting their points of connection or deviation; then return to photographing, and stripping, and placing, recording the stratification of stationery, how the printed images gave way to pictures cut from magazines, or to polaroid snaps, as an archaeologist might note alterations in pottery types.

If this is a mnemonic system, she said to me as she leafed helplessly through a particularly thick bundle of notes, and in response to something or other I had said, then so is my entire life.

![]()

Would Hunter Sidney have found this wall hard to explain, like Camillo in his memory theatre, stuttering at the attempted transition from clear mental picture to clear verbal form?

I did not ask Veronica to make the attempt, just watched her at work from time to time. But I did ask if she was not in fact missing an opportunity to do something extraordinary, and unwrite The Love Filter, reversing the order in which it had been written with the aid of the mnemonic wall.

I reasoned it thus: the whole thing could be said to have reached a point of maximal expansion, so that it should now gradually collapse under its own weight, as though Hunter Sidney’s death were some sort of catastrophic singularity in the space-time of his creation; characters should retrace their steps, be reborn in memory, wander off the spectrum of the narrative, working their way from the high-water mark of ordered relations as expressed by the final state of the wall, to their disordered starting point, where they did not yet know anybody, had not yet done anything.

It would take on now the form of an hourglass. A reader coming to it fresh would not only set the hourglass in motion, but would at some invisible point pass through the neck of the glass herself. It would be like the Divine Comedy with its inverted Hell and Heaven.

It would be, in the end, properly remembered. It would be, for a reader, like Veronica's own careful and wistful unmaking of the memory wall. We could only dream of such an act of remembrance of our own life.

For a moment a flicker of the old Ideal City animated me; I glimpsed The Love Filter as a failed object, an egregious bubble of order and activity deep within the World Wide Web, that would be perfected in its own serene and logical destruction, would find its ideal form in its own pre-existence; but Veronica I knew was content just to push on in search of a conclusion, if one could be found, and only tutted lightly to herself at my panicky and irresolute nostalgia.

![]()

Hunter Sidney cannot make his underworld journey alone. There are knots only we can untie. The knots of memory. Our circumambulation, like any commemoration, is how we will dismantle our memory theatre. Set him free.

At the top of Dickerage Road, Clarke pauses us all for a moment to admire the sub-monumental roundabout, built up in layers, he notes, like a compressed Ziggurat or enlarged clockwise dial of some sort, or, conflating his ideas, a dial to open an inverted subterranean Ziggurat; turned in combination it might, says Clarke, lead down, down, down, geometrically destining us, should we succeed in unpicking it, for the sharp end of creation; note for example, he adds chthonically, how the bottommost layer is a saddle-shaped flexing of square cobbles, a representation of the cosmos.

—dial—

Clarke wanders over to it before anyone can think of anything at all to say, not, as it turns out, so that he can operate the Stygian dial and release our friend from his nether-cursus, but so that he can prop his immense flat white trainer on it while he ties up an errant lace.

No one, yet, has mentioned Hunter Sidney, but Solomon now wonders aloud for us if Hunter Sidney ever made it up this far. Perhaps, he says, remarking on our previous failed navigation, the First Circumambulation was the only circumstance in a lifetime living on the fringe of Norbiton under which he might have ventured to the roundabout on Dickerage Road. What else could have led him here, to this lost confluence of wholly interchangeable streets? His ghost, Solomon, concludes, is not with us. We have somehow tacked out beyond him. We need to swing back into Norbiton proper now, and pick up him along the way.

There is no answer to any of that. There are corners of Norbiton which even I—cartographer, chronicler, archaeologist and necrologist of the Ideal City—have never seen, and we are anyway not currently in Norbiton. Most of our routes, in space as in life, are repetitions.

As Clarke returns from the roundabout, laced and erect, we are spat off on its centrifuge along Dickerage Road, and into Dickerage Lane. At the entrance to Mount Pleasant Road, Dickerage Road becomes Dickerage Lane, both nominally and qualitatively. Dickerage Road is a residential street; Dickerage Lane, for much of its length, is a narrow shoot of accelerating traffic which runs up and over the railway again by a narrow bridge, rising above residence and railway alike.

Old Sol’s mention of Hunter Sidney has opened the sluice of hyperlinked memory. Emmet Lloyd is excitedly telling us about the game of football we all apparently played on the Fairfield Rec the last time we were circumambulating (as he phrases it). Old Sol says he has arranged the little objects and some of the books which Hunter Sidney contributed to our library into a minor rebus of affection, invisible to anyone who did not know the man but legible to those who did. We should all pass by, he says, and read its runes.

Clarke tells a fabulous story about how he came to meet Hunter Sidney in his place of work, the Shell building at Waterloo; he, Clarke, recalls for us that at the time, just back from Rome, he was doing courier work and was directed up to Hunter Sidney on the umpteenth floor with a package for his signature, and as he went he marvelled at the partitioned labyrinth of the vast open floor spaces, how everyone looked at him but no one challenged him as he passed islands of desks because, in his imagination, they all knew he was going the wrong way, that the centre would always elude him; that eventually, finding Hunter Sidney, they fell to talking about labyrinths, and struck up a friendship which lasted in perpetuity.

By now we are passing the Dickerage Lane Rec. and Adventure Playground. We stop and contemplate the brightly coloured play equipment rising like the castles of fairylond over the rusted embattlement of the railings.

—Fairylond—

As we stand there I produce from my pocket for the company to inspect the Etruscan lamp which Hunter Sidney stole from the Villa Giulia museum in Rome, and which Mrs Isobel Easter gave to me with instructions to repatriate. I am yet to act on those instructions for one reason or another, and Mrs Isobel Easter has asked me to bring the lamp along today so that she could be partially present. When everyone has held the lamp for a moment and turned it over in his hands, in her hands, I wrap it again and replace it in my pocket.

On the far side of the railway bridge the lane is reintegrated into the residential system of Norbiton. We are back once again in the city of men and women. Pre-fab houses and small businesses and a primary school and mature plane trees line the streets. At the corner of Kingston Road, the end of the Circumambulation proper, we file into the Prince of Wales for a pint. We are the only customers this early, and we stand there, over the scrubbed black floorboards, in this bleak spare space, silently libating. Our walk done, life, we silently agree, can now slowly start again.

![]()

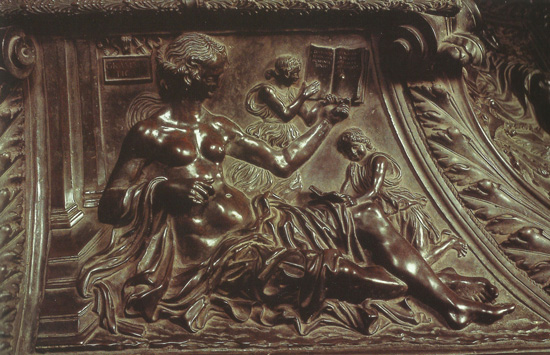

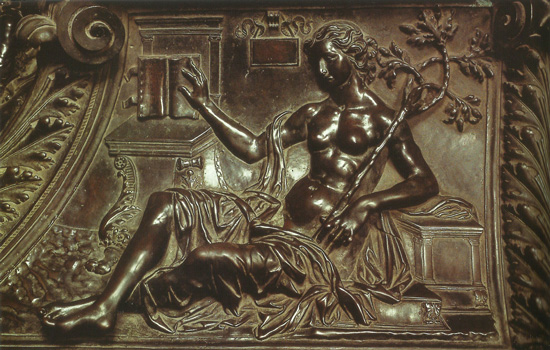

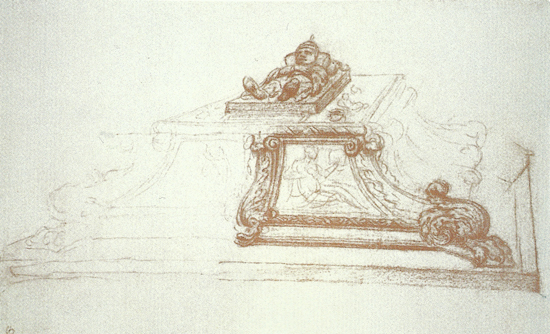

Between 1484 and 1493, Antonio del Pollaiuolo produced a tomb for Pope Sixtus the IV (1471-84). The tomb is a floor-standing high relief, with an effigy of the pope lying on a bier, with panels representing the virtues and the liberal arts—in the words of Giuliano della Rovere, nephew to Sixtus and the future Pope Julius II, who financed and largely conceived the construction of his uncle’s tomb, the tomb is ‘ornamented with the virtues’.

—ornamented with the virtues—

– Tomb of Sixtus IV,

Antonio del Pollaiuolo

Giuliano della Rovere clearly had opinions about funerary monuments. His own would be long in the planning and incomplete in the execution, a vast marble confection ornamented with various drooping slaves and otherwise doleful individuals.

But his conception for Sixtus’s tomb, almost certainly amplified by the ambition of the artist, was altogether nimbler. Rather than the mourning and wonder that he wished to elicit for himself, it presented an array of tools for the reconstruction of the Ideal Sixtus, Sixtus as he might have represented himself to himself: the humanist, the man (quite literally) of parts.

There he lies, toothless old bird, his intellectual attributes and humanist credentials piled beneath him like a hoard of despoiled weapons and trophies.

—credentials—

– Grammatical,

Pollaiuolo

—weapons—

– Geometrical,

Pollaiuolo

—trophies—

– Rhetorical,

Pollaiuolo

It was, in effect, a mnemonic aid. Francis Yates has speculated that Giotto’s iconography of the virtues and vices in the Arena Chapel in Padua was derived at least in part from medieval mnemotechniques—the painted figures were, in other words, examples of the sort of strange images that a trained mind would store away.

So too with Pollaiuolo’s tomb. Both it and the tomb which Julius II originally designed for himself were properly ambulatory memory systems. You had to take a stroll around them, either in fact or in imagination, in order to remember their proper object.

![]()

The question remains what that proper object was. Not the individual whose bones lay within. His memory was cast in terms too conventional to conjure the actual man. Rather it conjures, say, the best of a culture which found itself nearest to accomplishment when it approached and circled for the umpteenth time these odd insoluble iconographies, like strange attractors, hieroglyphs of beauty.

This seems to us now a recipe for loss—the individual is submerged in a welter of conventional gesture. But perhaps it is best to subsume the individual after death into the pattern of the time. When we die, we are accepted into a whole culture and history, no matter what we were in life. There is no desperate clinging to the quiddity of an individual, as though to the last drops of water on earth. What sticks in the mind sticks in the mind, and is sufficient.

As we slip our moorings in the Prince of Wales, we divide. Clarke takes himself over to the allotments (an entrance to the Rec. lies directly opposite the pub), and Old Sol goes with him to pick up some promised vegetables; Emmet Lloyd turns back down the Kingston Road going out of Norbiton, destined who knows where; and Veronica di Viggiani and I walk along the Kingston Road back into Norbiton. And there at the threshold of the invisible burgh, near enough, we run into Kelley and his dogs. He is standing, an unsmiling sulphurean presence, outside Fat Boy’s Cafe and Restaurant, and watches us as we approach. And as we approach, twenty metres short of Kelley, we cross the Norbiton threshold, its boundary stone.

—Norbiton Threshold—

There will be, I am suddenly aware, a test. We were always to be tested at the boundary. It was destined. And Hunter Sidney, I am momentarily sure, is equally being tested in an alternative realm. There is some boundary to pass, some beetle or crocodile to assuage, down there; what we bind up here on the sunlit surface will be bound in Tartarus; and so we approach the smoking demon and his dogs; and he just smiles and nods, at me and his daughter, passing and smiling back in the sun. The dogs are sleepy. No one says anything. Kelley inclines his head to the diner door, and we follow him in, for eggs and bacon and a cup of tea. There are no demons after all all. There are only the quick and the dead, the sunlit and the eternally dark. And in that moment Hunter Sidney’s way is unlocked and he is imperceptibly on his way, in freedom, to his long home.

—ornamented with the virtues—

– Tomb of Sixtus IV,

Pollaiuolo, sketch by Marten van Heemskerck