Accidental

—let us fall—

– The Tower of Babel

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Let us fall, like a mason of Babel losing his footing, toward Norbiton, out of the blue and unresisting sky.

We grab at the scaffold, and are gone. Our trowel and our hawk, a handful of tumbling bricks, keep us company. It is a long way down. We bounce against projecting masonry, are set moving in eccentric spirals. Our descent is a rapid unravelling.

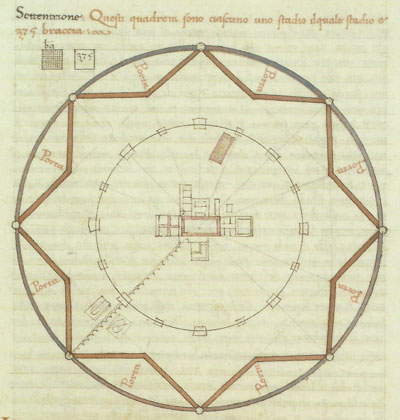

What do we see, spread there below us, as we rotate thus giddily earthward? On what yard of soil will we elect to land? Because, if we remain true to our downward trajectory, a more interesting reality awaits us. Down there, barely visible against the confusion of streets and houses, drawn with a finger by some idle deity in the chalks and brick dusts shaken off by the great tower, are the lineaments of a clear and beautiful plan: the groundplan, no less, of the Ideal City. The Ideal City of the Failed Life. Norbiton.

—rotate giddily earthward—

– Plan of Sforzinda

Filarete

![]()

We come to earth, then, with little a flex of the knees, and look around. Not much to see, from the ground. Norbiton is an undistinguished place. Perhaps not a place at all. The stones of Norbiton resound neither with history nor promise. No one stands on the brink of Norbiton Avenue, Norbiton station at his back, and feels excitement, curiosity, trepidation. No one will ever tell you either with pride or as mere matter of fact that she lives in Norbiton. Or that he or she comes from Norbiton or is on his or her way to Norbiton. We will say Kingston, or London. Never Norbiton. Norbiton is a cloaked city.

Mostly cloaked. Some fragments protrude. There is the station, after all, and Norbiton Avenue. There is a pub called the Norbiton (not actually in Norbiton but over the border in Canbury), which was once the Norbiton & Dragon, and in living memory there used to be a kebab house, the Norbition Charcoal Grill. But you will not, in the normal course of things, notice Norbiton, not even if you live here.

—not actually in Norbiton—

If you ask any resident of Norbiton (can you find one?) where it starts and ends, what it is, they will not know. Back when I had a job, a man once stopped his car on the London Road to ask me the way to Norbiton. I was bewildered. This is it, I said.

What was he thinking? What could he possibly want? (I would add now: How could he see me? How did he know we existed?) You cannot go there, I should in full honesty have shouted after his disappearing (dematerialising?) car, because there is no there.

And yet it has a name, a name this driver knew and was able to use. It is called Norbiton. A name is something to work with, something to hang your concepts on, if also a way of generalising, of forgetting. Give something a name and you seem to know what it is, it is no longer strange, it is a portable mental object, so much loose change jangling comfortably in the pockets of your mind.

To keep the name useful, however, to keep it sharp and unaccommodating, it needs to be treated as a term in our understanding of the world. It needs to be anatomised. At any rate that is what we have done, and in the process, we have learnt to distinguish between three Norbitons: Accidental Norbiton, Empirically Real Norbiton and Norbiton: Ideal City.

And so this Norbiton which has grown like moss or nettles in the interstices of more substantial, more purposeful places—Kingston, Wimbledon, Surbiton—we call Accidental Norbiton. Accidental Norbiton is a non-rationalised space; it is a space, that is, conceived as a bucket or other receptacle filled with a cluster of objects.

Those objects are destinations of one sort or another. Norbiton, like any place, is criss-crossed by vectors representing small and automatic journeys, journeys to and from, or between destinations. But none of these separate journeys would induce you to link the destinations together as some coherent mental whole. You have no object-specific neuron which fires consistently at the idea of Norbiton, as you do, for instance, for Jennifer Aniston1.

—object-specific neuron—

– photo: Angela George

We have no paradigm for this kind of place. Accidental Norbiton is contingent, marginal, superfluous, an ugly necessity: it is the wires coiled under your desk, behind your bookcases; it is the suitcases gathering dust under your bed, or on top of your wardrobe. It is an adjunct to living, part of the logistics, the bureaucracy, never what you might call life itself, the movement and centre and focus of which seem to prevail elsewhere.

Perfect, then, for a life of well-judged failure. You can fail anywhere. There is no end of ways to fail. But you can fail more rapidly and more expertly, with superior clarity and precision, in Norbiton.

![]()

Empirically Real Norbiton is merely Accidental Norbiton reconstituted as a coherent whole. Those points and destinations and fragments are no longer bits of other places: they coalesce, become a sort of entity, a small pocket of space in which you can live your life, self-sufficient and (not very) productive.

The empirically real city was there all along; all that was necessary was to notice it. However, since all noticing must battle a perceptual inertia which prevents us seeing anything not automatically conforming to our modes of cognition2, the only way anyone is likely to look properly at Norbiton and to understand it as a coherent location in its own right is to be forced by circumstances to look at nothing else—and losing your job is a good way to start.

![]()

But I did more than lose my job. I abandoned my career – as a lecturer in and scholar of Renaissance Studies – beyond any hope of retrieval. I resolved never to go to work again. To jack it in. To dump the entirety of my life and see what happened. That more or less did it.

The abandonment was a true failure – true because it did not compromise, did not stuff its pockets with phone and keys and wallet before it fled the burning house. It embraced, and in embracing, scorched to cinders my professional, personal, social, and communal life. I had some modest savings, a bit of credit, belongings I could sell; enough to stretch a reduced and spare existence over the span of eighteen months, perhaps two years if I did nothing, went nowhere.

I regarded it as an experiment with no control, one which would provide data at once interesting and useless. An experiment in wholesale, purposeful, quitting.

In that curious state, I started to walk the midweek streets of Norbiton, and in this way I began to see that there was a place here, an invisible place, and that its residents were camouflaged, stealthy, anonymous.

And it is more than mere anonymity. Go out, walk the streets, buy a paper, get a pint. No one will be able to retain a memory of you that outlasts the exchange. Finish your pint, leave your paper on the table in front of you, nod to the barman, walk out of the pub, and in a few minutes the memory of your face will be no more vivid to anyone who encountered you than the impression of your arse on the chair you have vacated, and perhaps less so.

—impression of your arse—

– Study for the Birth of the Virgin

Domenico Ghirlandaio

Taken the right way, this is an intoxicating freedom, not unlike, it must be supposed, the religious ecstasies of hermits. You have slipped under the World’s radar. Stop moving and you do not, shark-like, die. You float down, down, down, and then find that there is, in fact, a bottom, peopled by odd cartilaginous creatures of the deep compressed into strange shapes by the pressure, and going about their business.

These are people for whom the world of work intersects only obliquely and intermittently with their own, and a world in which poverty, or indigence, or impecuniousness, are remorselessly local. Impecuniousness ought to lead to a lightness of spirit, a weightlessness; but it doesn’t: it drags us slowly earthward, locks us into a few narrow streets.

I viewed all this slow deep sea life not with the detachment of a diver but with the bemusement of a drowned man who finds that he can breathe. Whatever else, the lineaments of this new place were substantial if hard to make out, like the traces of some sunken wreck attracting crabs and urchins and bloated blind fish, and growing coral.

It turns out that Empirically Real Norbiton has a centre and a shape, then, and an intricacy and complexity perhaps in advance of that of Accidental Norbiton, determined as it is by more marginal but more consequential issues of survival, subsistence, resourcefulness, suspicion and occasionally a remnant solidarity.

A perilous world, then, long on suffering, but a world where the vectors of Accidental Norbiton join into something coherent, if, admittedly, shit—a place, in other words, that you could hope to escape from, not an ontologically indeterminate region of space.

![]()

In trying to describe the arcane geography of the Ideal City, I realise that I am providing not a map but an assortment of transparent overlays to a mess of maps. Frankly, it is not an easy place to visit.3 It hangs improbably in unstable suspension between eerie gravitational masses – Accidental Norbiton and Empirically Real Norbiton among them.

To put it another way, you will not find Norbiton: Ideal City in Empirically Real Norbiton any more than you will find it in Accidental Norbiton, but at least something is now in play. I have a romantic notion that it is in, or more precisely, from such ancillary culverts as Empirically Real Norbiton that new things emerge, and that, if there is any sort of critical mass in our civilisation, any sort of louring or inarticulate determination that things—what things I hardly know—but things, can be, for a spell, different, then this is where it will break out first. This is where the vortex will start to spin.

I do not know if what we have in the Ideal City is a forming vortex, or just a coincidental but resonant impatience on the part of a slack handful of individuals with the incoherence of this life, and a conviction of its (provisional, temporary) perfectibility.

I am groping for clarity and coming up with something else, as if the object I wished to grasp, to hold up, rotate, study, understand is not after all susceptible of direct observation. The big things never are. You deduce them, see them askance, by inference.

But let us anyway postulate that object and give it a name, and let us call it The Failed Life.

![]()

It please the Norbiton academicians to distinguish between success, failure, and the Failed Life. Norbiton: Ideal City is the City of the Failed Life.

But in making that distinction, in saying that the Failed Life is something beyond mere success or failure, we do not deny its provenance. The Failed Life is a pragmatic and coherent, if somewhat oblique, answer to a series of linked questions thrown up by catastrophic personal failure—specifically, our own.

—questions thrown up—

– Phaeton, 1533

Michelangelo Buonarroti

How, we ask, can an individual survive acute and systematic failure? How can you expect to organise a meaningful life for yourself when the organ of Ambition, or Purpose—that by which, perhaps unconsciously, you had been accustomed to grade and sort and filter every aspect of your life—has been lobotomised?

Can total failure be a form of fulfilment? Or is such failure nothing more, in the end, than a crisis of reorganisation, a point of maximal stress in a life of complex torsion? Inevitable, in other words, and therefore banal?

Our answer to all of these questions lies in the Failed Life (a practical and not merely philosophical response, note), and by extension in the whole polity of the Ideal City; and it is laid out in the Anatomy which describes that city. But in making that slightly evasive deferral, it is perhaps also worth stating the plainly obvious: that, whatever else, the answer to the problem of failure is most assuredly not success.

![]()

So when I quit my job I watched not just my career but the whole complex of society and its ambitions and goals recede into the past, the distance. I was not unemployed, not resting, not breaking down. I was properly and thoroughly disoccupied, an indecipherable fragment of the lost civilisation that had been my life.

The Anatomy of Norbiton is partly a description of the new order and the new structures [Norbiton: Ideal City] which eventually emerged from the rubble of the old [both Accidental and Empirically Real Norbiton]. But I had no inkling of any of this when I quit my job, or in the months following. And so to provide myself with some new co-ordinates by which I could situate myself, I found myself using the Classical distinction between otium and negotium (disengagement from and engagement with the world, respectively) to rough out the zones of my life, give it some sort of broad form: like scratching out the perimeter of a new city in the dry earth with a pair of oxen and a plough.

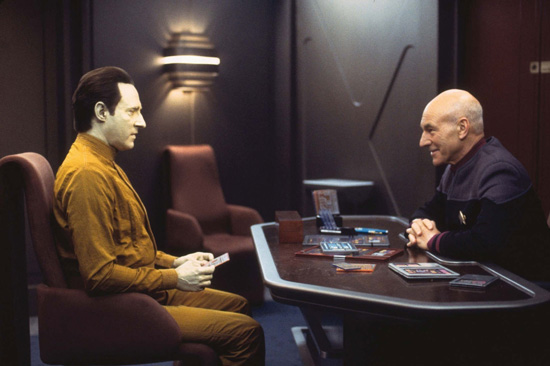

I should also note, however, that, day to day and less grandiloquently, I gave my life structure and order by watching a lot of Star Trek. Or rather, watching all if it. The Original Series (TOS), The Next Generation (TNG), Deep Space Nine (DS9), Voyager, Enterprise. All of it, in order, episode 1 to episode 727.

Sometimes you just find structure lying around.

—structure—

![]()

The Star Trek months were, psychically speaking, a necessary idleness, an uncoiling, not unlike sitting motionless in the woods, waiting for woodland life to reassert itself, one squirrel at a time. I set no limits and had no expectations.

Part of the matter which was taking form was a tendency, on my part, to schizoid retreat. It was a tendency to which, in quitting my job, I gave full rein.

Schizoid has nothing to do with schizophrenic, apart from the etymology. As I understand it, it is characterised by a pronounced preference for your own company.

Carl Jung, psychologist and noted schizoid, allowed himself to fantasise a room in a tower on an island (a fantasy he partly realised in his lakeside tower dwelling at Bollingen, his "confession of faith in stone"); you reached the room through a trapdoor in the floor which could only be locked or opened from the inside. You would go up into your study, shut the trapdoor, and enjoy the silence, for days and weeks and months if you remembered to bring enough tins of pemmican with you.

In my own case it was sufficient merely not to answer the door or the phone. No one wanted to bother me anyway. I spent twenty, twenty-one, twenty-two hours a day in my room, and felt wholly unconstrained. If you do not rub up against people or the obligations which people entail, you do not notice your own discontents. It is the shoe that pinches the foot, not the other way around. Allow your life to splay out over a boundless inner space and, assuming you are not troubled by the infinite blandness of being and do not crave or require the presence of others to remind you that you exist, then your life will find its own level.

![]()

It was towards the end of my powerful initiation into Star Trek that I met Civ Clarke, Green Man of Norbiton.

—Green Man of Norbiton—

Clarke says of my Star Trek habit that it was the result of not being allowed to play enough as a child. He said that I had probably had academic parents (not so), that they had probably made me do my homework; all of this confirmed his hypothesis: that the play instinct had become etiolated in me, and quitting my job meant nothing more than playtime.

But there is a bit more to it than that. Or perhaps I mean a bit less. As I understand it, my Star Trek episode was not about escape, but about the imaginative play of the schizoid in my soul.

I think of it like this. You could fit out a ship for a five-year journey, and glide through space, hidden and protected by the whole apparatus of shields and cloaks and sensors and phasers and quantum torpedoes. In the last episode of Star Trek: Voyager the ship clanks around in something called ablative armour—purloined from The Future—which seems to make it impervious to everything. And then there’s an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation which revolves around a Starfleet prototype phased cloaking device, which renders a ship and its contents not merely invisible but fractionally out of phase with normal space-time, enabling it to pass through solid matter4.

I’d have all of that. Imagine the serenity.

![]()

I sat therefore in my apartment drinking tea, reading whatever it occurred to me to read, watching Star Trek, talking to no one. It was an accidental progress of the soul, gently incorporating the stumbles and pratfalls of consistent failure into the idiosyncratic choreography of the Failed Life.

And so when this otium, this prolonged vita contemplativa, came to an end, I was surprised. At a certain point in your life you imagine, for the most part correctly, that all of its key elements are now assembled: you have met all of the important people you will ever know, you will not generally surprise yourself with unknown abilities or character traits, you know yourself professionally and socially, it is too late to learn a new skill such that it will be life-defining and not merely an ornament, a hobby; and so on.

The seismic shocks of experience can strike at any time—someone might die, or a bank fail, or a flood come—and change the balance of elements irrevocably. But these are predominantly negative events, removing blocks and spars from your stock of building material. New constructive elements or principles or technologies do come along from time to time, but any new element that is added will be brought within the powerful gravitational system of what already is. All that remains is to shuffle things around, hoping perhaps for cabalistic penny-dropping if you are an optimist, otherwise merely passing the time and reflecting on what has been.

I see now, however, that my period of otium, in removing the great delirium of work from my life, had not just cleared ground per se but had cleared ground that someone would sooner or later want to build on—perhaps me.

There would came a point, in other words, where I needed to enter the world again. Just that. Enter the world and take my station. Dock with the Enterprise and report to the bridge. Keep my schizoid ship ready to sail in one of the cargo bays, perhaps, in case I required a quick exit, but take my station nonetheless. I allowed myself to harbour a hope that, in the course of whatever time remained to me, I would be able to map some portion of the galactic complexity of my life—no more complex or galactic, I should say, than anyone else’s; that I would be able to lay down, as Yourcenar’s Stoic Hadrian has it, not a philosophy by which to live, but rather a coherent cluster of techniques through which to exist.

That from this cluster I would in short order have assembled the building material of the Ideal City, I could not have guessed.

—coherent cluster—

– città ideale

anon., variously ascribed

![]()

The cities painted by fifteenth and sixteenth century Italians are for the most part stage sets hosting scenes from the great biblical careers—Christ and his saints and their oppressors locked into stories of beheadings and stonings and griddlings and flagellations, conjurations and refutations and annunciations. And on and on, to salvation and apotheosis and all that upward movement of the spectred soul.

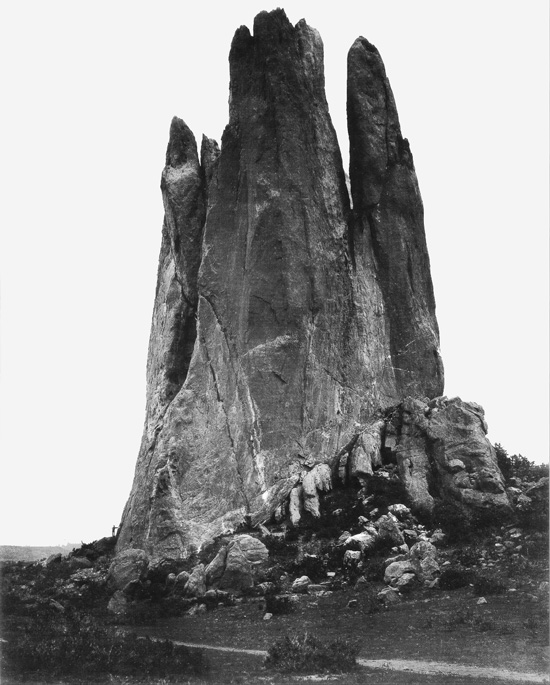

But a city, seen from the air, is empty. Our tumbling mason, in his sublime barrel roll, does not see suffering humans, intolerable chains, dulling routines, the cracks in the pavements and the weeds and tares growing up in the citizens' minds. He sees, only, an idea of a city. Stadt Luft Macht Frei, said the cities of the Hanseatic League. City Air Makes You Free. For our mason, for now, there is nothing but Stadt Luft. The city itself is transfigured to air.

The maker of the città ideale knew this. The town is properly empty. A firm line has been drawn under all that history and meaning. You would walk across that square and there would be only the sound of your own footsteps and perhaps a breath of wind, and there would be the reassuring chill and clarity of a lucid dawn. People will shortly emerge and go about their work (they do not have jobs, just lives and work intertwined like nerves and pumping blood and muscle), under no illusion of salvation, no pretence of fulfilment, intent only on inscribing with their routines a little transient shape on the stone city.

There might even be, from time to time, an emergent sense of purpose. But it would be no more than a form of local sanity, because by eliminating the typological resonance, the pregnant history, the opaque struggle for salvation—the grand narrative frameworks, in other words, of universal success and failure—the city reverts to a comprehensible size.

Just so with Norbiton. Norbiton: Ideal City is a haven for the Failed. There are no tyrants to flee here. And there are no jobs to quit. No one is expected to pitch in, to rub along, to cheer up; no one is ever shouted down, stepped on, chivvied along or shut out. Everyone is afforded the space they need.

We have failed, acknowledged our failure, and moved on.

![]()

Here, then, is our accidental mason, strolling the Ideal City, trowel in pocket. The great dark tower above is gone in a simple cataclysm of the imagination, and the sun shines down on him.

—simple cataclysm of the imagination—

– Tower of Babel rock formation, Colorado

William H. Jackson

His fate is not unique. Arion of Lesbos, a singer credited by Ovid with Orphic powers, won a singing competition in Sicily, and embarked on a ship for Corinth and home. So the story goes. But the sailors envied the rich prizes he carried with him, and resolved to murder and rob him. Arion, in despair, pleaded permission to play one last time. They agreed, but the poet, having sung his song, cast himself into the waves, whence a dolphin emerged to bear him away to safety, Arion still singing and playing upon the creature’s back.

These then will be our emblems of The Failed Life. The mason with the trowel in his pocket, looking for honest work in the sunlit city. The drenched and carolling poet, making good his escape. We have cast ourselves from your crooked prow, oh Accidental City, but the Failed Life, strange and beautiful, bears us on, still singing.

—still singing—

– Arion, Albrecht Dürer