Restorational

—marked for life—

– Legend of the True Cross, Death of Adam (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

In the late 1970s, my brother’s chemistry teacher—ex-ICI, white-coated, old, cynical, impenetrable—drank gin and smoked in class. So my brother says. The fumes of gin and smoke would swirl directionless, mixed with the acrid generational stench of ammoniums and hydroxides and sulphates.

On one occasion, my brother relates, the old man rolled up his sleeve, an Ahab of industrial chemistry, to amaze his class with a sight of the yellowing acid scar that ran down to his elbow. In his professional days he had, he said, poured his acid too slowly, and it trickled down the jar and along the wrist and dripped off his elbow, and there he was, marked for life.

I was never in his class. I never saw him in the flesh, never saw his excoriated arm. He retired—or was retired—for good and all before I started. He was a mythical, acid-bitten presence in the pre-cosmos of my schooling. One of the old gods.

![]()

Let us examine the scars of the old gods.

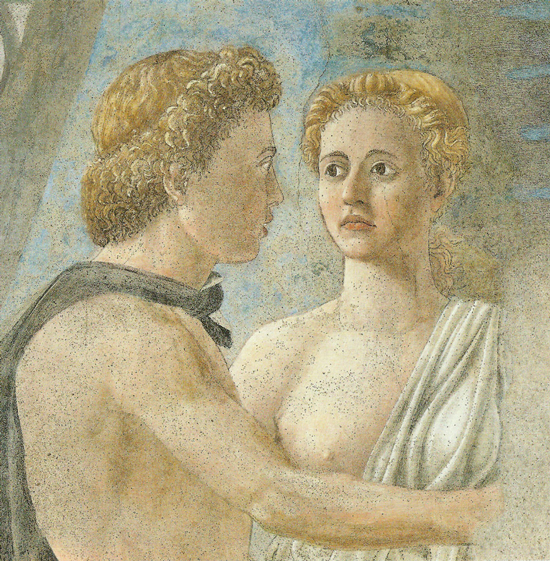

In the 1450s, Piero della Francesca, picking up a commission left dangling by the sickness and death of Bicci di Lorenzo, painted the apse chapel in the church of San Francesco in Arezzo with scenes depicting the Legend of the True Cross.

Among the various tableaux are representations of old men awaiting death. On the right of the first lunette, a failing Adam, scared to die, dispatches his son Seth to the Gates of Heaven in search of a remedy, a miraculous ointment.

—in search of a remedy—

– Legend of the True Cross, Death of Adam (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

There is no ointment. There is no remedy. Or rather, the remedy is of such a prodigiously convoluted nature that it will take all of history in the unfolding.

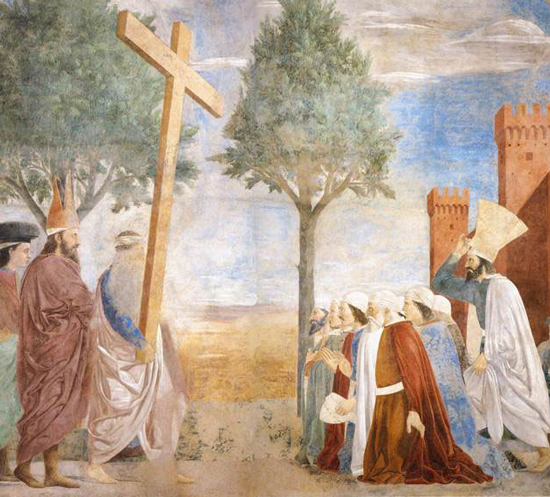

On the opposite wall the youthful Emperor Heraclitus, in a distant and obscure ramification of the same story, is overthrowing the Persian despot Chosroes in battle, and, to the right of that scene, Chosroes is resigning himself to execution by beheading.

—beheading—

– Legend of the True Cross, Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

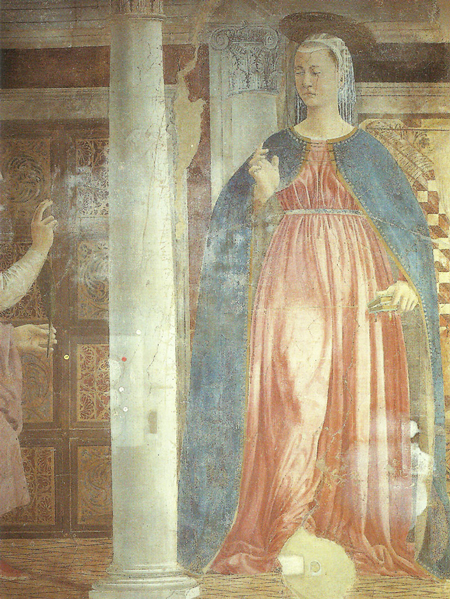

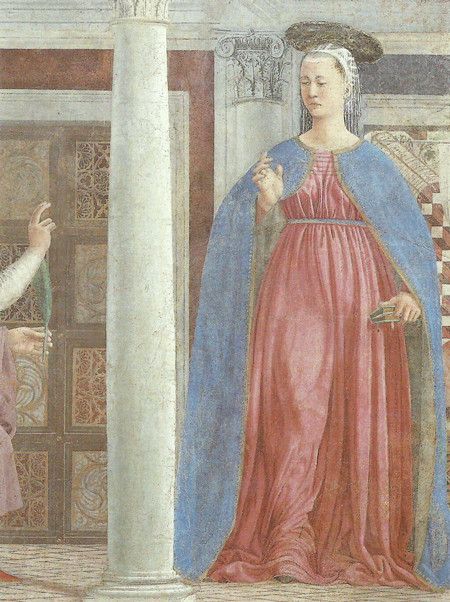

And on the rear wall, God the Father is presiding over the Annunciation. It is at the moment of annunciation that the incarnation occurs, the incarnation of the son who will overthrow his hoary old father’s covenant.

—hoary—

– Legend of the True Cross, Annunciation (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

God the Father and Chosroes are in Piero's fresco one and the same man, pounced from one and the same cartoon. Is Chosroes an avatar of the old god? Or is the old god just another pagan king, long in the tooth and ripe for usurpation?

It is a tortuous cycle, hard to follow, full of sacrifice. When Seth returns from the Gates of Heaven, it is not with an elixir of life, or a pardon, or a remedy. It is with a splinter of the tree of knowledge that he is to plant under the tongue of his dead father, from which will grow the tree which will provide the wood of the cross.

Centre stage in this cosmic drama will be not the father but the son, crying his virile tears in Gethsemane. The old gods will have only their scars, telling them they once lived, directed empires, walked in paradise, separated light from dark.

If there is to be a recovery, in other words, it will be by a hill and asperous way1. And it will not involve the restoration of kings.

![]()

A fine double crack runs up God the Father’s right shoulder in Piero’s fresco, the two tributaries joining at about the level of his mouth and running up towards the halo.

—fine double crack—

– Legend of the True Cross, Annunciation (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

Fresco is a fragile medium. What is painted fast in youth will dry, the fabric will crack with age; fixed in position, it will be subject to the agues of climate and the neglect of centuries.

And this is a fresco that has suffered more than most. Piero himself was called back to undertake restoration after an earthquake in 1483 damaged his work. Three other major seismic shocks are on record in the fifteenth century—in 1427, 1448 and 1456, causing shifting and settling in walls which had anyway been constructed (1366) on irregular ancient foundations.

In the sixteenth century the small domed campanile was replaced with a large tower, which promptly slumped against the wall of the chapel, causing much of Adam’s tree to fall in. Economic difficulties in the centuries that followed led to neglect of the fabric of the church, and in particular of the roof. Leaking caused colours to leach, plaster to swell, and ultimately the great plague of fresco, sulphation, where various soluble salts in the walls rise in damp conditions to the surface and interact with the calcium carbonate to form calcium sulphate, and so the painted image suffers spectral whitening, pulverescence, vanishing.

—spectral whitening, pulverescence, vanishing—

– Legend of the True Cross, Death of Adam (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

Further foundation shifts in the 18th century cracked the walls still further. In 1785 a bolt of lightning struck the heavy old campanile and various fresco pieces in the top right corner were lost. By this time the church had been deconsecrated and Piero’s work was largely forgotten. French troops billeted in the building during the Revolutionary Wars fired musket balls at the figures and scratched graffiti in the soft surface; they also suspended a huge wooden beam across the chapel mouth from which they hung curtains for a makeshift theatre, embedding the beam directly in the plaster.

In 1858 monks called in a painter to ‘restore’ the frescos, and between 1901 and about 1915 extensive restoration work both on the walls and the frescoes saw large quantities of cement pumped into various cracks and gulfs in order to stabilise the structure, but this only accelerated the suphation. By the time Kenneth Clark published his monograph on Piero in 1969, the vast lacunae in the fresco had been filled with neutral bands of plaster, making it almost impossible to read the jumbled and broken narrative.

A fresco, then, of sorrows, and afflicted with care.

![]()

Down here in Norbiton, far removed from all those tales of cosmic restoration, we bob about on our own undramatic tides.

Solomon—not the patriarch, but the custodian of our Ideal Library—is shutting up shop and going out to see the world. His re-reading project is incomplete or suspended, his proof-reading project shucked off2. Time, he says, to let in a little light, see something new.

—see something new—

– Legend of the True Cross, Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba

Piero della Franscesca

We are in the garden of Mrs Isobel Easter, which he has asked me to show him before he leaves on his various trips. I have talked to him about Mrs Isobel Easter and about the garden a good deal. I do not know if this is part of his project of getting out into the world. If so, I am happy to oblige. And so is Mrs Isobel Easter who, if nothing else, takes a vicarious pleasure in seeing one of our most unwinkleable Cyclopes emerged into the light.

She has made us gin-and-tonics, a timbre-altering chemical infusion, and we are examining our world under their lights. Solomon tells us that his first port of call will be Cochin, now Kochi, in Kerala. It is the town of his birth: he is descended from Cochin Jews. His family moved to Tel Aviv after the war, and he was subsequently sent to school in England, where he stayed. He still has a sister in Tel Aviv, he says, and plans to visit her after seeing Kochi. And then, who knows. Arezzo?

He laughs. He is, he says, an incurable solitary. No wonder that he is planning to return to the world in a place of strangers, a place where none of his people, none of the descendants of his ancestors, still live.

What will he find there? The wind, the rustling bushes, perhaps, the desert emptiness of his defunct Old Testament God, peaceably lodged with his ancient brethren, Shiva and Vishnu and Shakti and their innumerable avatars, all those welcoming old Hindu deities, temple abutting temple.

![]()

Solomon tells us something of the history of the Cochin Jews.

Jews started to arrive in Kerala no one knows precisely when, perhaps as early as the sixth century BC following the siege of Jerusalem and the destruction of the First Temple, more certainly after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70AD.

That first wave, which had settled in Cranganore a little further north but moved to Cochin after the fourteenth century, was followed by a second in the sixteenth century, after the expulsion from Spain. The two groups, the so-called Malabari and Paradesi (or Black and White) Jews, never fully integrated with one another. They spoke different languages and the Paradesi Jews, having trade connections in Europe and some European languages, gave themselves airs and got rich. Both groups kept slaves descended from the union of Jews and Indians, or manumitted slaves brought by the Sephardim, who constituted a third distinct group, the Meshuchrarim.

Cochin Jews were a distinct community, with traditions derived from the Hindus and Muslims amongst whom they resided. They entered the temple barefoot, wore different colours on different festivals, and on occasion distributed grape-soaked myrtle leaves to the congregation.

This proliferation (never great in numbers) came to an end in 1947-8, after Indian independence coincided with the creation of the state of Israel. The Cochin Jews departed, leaving the temple and perhaps 100 individuals. One hundred individuals in a population of a billion. No more than a trace element of humanity. An irrecoverable, fragmentary cultural code.

![]()

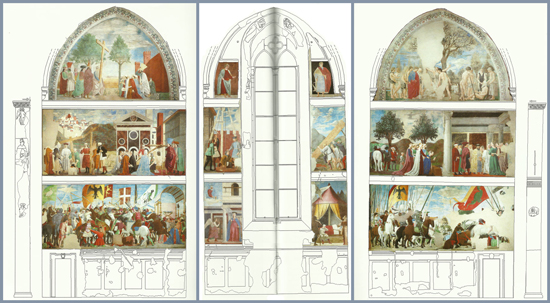

Piero took pains to make clear (if necessarily skewed) spatial sense of the grail-like romance of the True Cross.

—necessarily skewed—

– Legend of the True Cross, Chapel Plan

Piero della Franscesca

A frescoed chapel, in despite of the demands of linear perspective, requires the viewer to move up and down and back and forth. It cannot be properly read from a given spot.

You have to piece the story together for yourself. The conventions for laying out narratives in chapels or churches in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were complex if not arbitrary; in some you would read up and down from one wall to the next; in others it was necessary to read across, zigzag this way and that. Chronologies might or might not be respected, the fall of natural light might or might not come into play, as too might the theatre of the liturgy.

Painters faced scene to scene in typologically meaningful patterns across the painted space—so, in Arezzo, Piero has paired the battle scenes (of Constantine and Heraclitus), the vision scenes (Annunciation and Dream of Constantine), the female intuition scenes (Queen of Sheba, Helena) and so on.

These days they provide you with laminated cards parsing the order of the panels for you, and while the science of lamination was wholly unknown to Piero and his contemporaries, the stories were not; by hunting up and down for known markers—the cross, the dream, visit of Seth to the Gates of Heaven—you would be able to gather together the various strands, recover the story from the welter of images.

And as you worked to the end, placing the objects of contemplation not only in a chronological but also a meaningful order, you would experience the satisfaction, even mild exultation, of having cracked a conundrum; and cracking a sacred conundrum in the fifteenth century was akin to having trodden out a meditative labyrinth.

—mild exultation—

– Legend of the True Cross, Exaltation of the Cross (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

We no longer exult in the labyrinth. We might enjoy the conundrum, but this is not our personal salvation laid out here; we will not emerge from this process ourselves restored.

Which is not to say we do not have labyrinths of our own devising.

![]()

For thirty years, Solomon, deep in the recesses of his shop and we must suppose his various emotional or psychological predicaments, worked on his re-reading and his proof-reading projects, tracing the invisible hairline fractures of a culture, while simultaneously, unconsciously, searching for his own name, writ in error into the literatures of the world.

Thirty years of Talmudic meditation that was never, in fact, a reading or re-reading project at all, but an overwriting project: overwriting the reams of code that make a life by daily repetition of a simple but absorbing task. In this way, retracing, reordering his steps, writing around the bad sectors, the lacunae, the corruption, he recovered himself.

It was a long standing-by of the soul.

![]()

He sits here now in front of us, a functioning individual. He is an avatar of himself, he tells us, a fresh configuration.

He relates that the synagogue in Kochi stands next to the Mattancherry Palace, which has sixteenth century tempera murals depicting scenes from the Ramayana, the saga of Rama, the blue-skinned god, seventh avatar of Vishnu.

—Mattancherry Palace—

– Photo: Ranjith Siji (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The palace, built by the Portuguese in traditional Keralan style, has recently been restored, with some re-wiring and replastering, the cement floor torn up and new teak boards put down3.

Memory, says Solomon, does not inhere in the material form; it is merely represented by it. In Mattancherry there is no anxious drive to conserve bits of the true cross, so to speak, the original materials. In restoring it you cast around for what lies to hand, is sound, useful; and you go with that. You create something new: an avatar.

The old, the authentic, lingers like a powerful idea, the originary ship of Theseus, a ghost-shape.

![]()

The restorers of the Arezzo frescos in the 1990s chose to attack the problem of suphation with the application of barium hydroxide, the so-called Ferroni-Dini method4, which not only stabilises the painted surface and the intonaco substrate, but re-coheres the paint layer, pulling the colour free of the sulphurous impurity. The fresco as we know it today is a chemically re-engineered artefact.

—sulphurous impurity—

– Legend of the True Cross, Death of Adam (detail, pre-restoration)

Piero della Franscesca

—chemically engineered—

– Legend of the True Cross, Death of Adam (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

A fresco, however, is a complex and layered object. Piero in fact used many substances not compatible with fresco—verdigris, lacquers, oily temperas and white lead—so that it is not sufficient merely to dab the surface with a magic swab; there is a micro-landscape to know and respect.

Thus the restoration became a fifteen-year standing-on-scaffolds, a learning-to-read of surfaces5, a painstaking navigation of layers: routines and practices that for better or worse themselves became part of the fresco; the fresco that now exists, the new speculative, composite, contested object, avatar of Piero's original.

—original—

– Legend of the True Cross, Death of Adam (detail, pre-restoration)

Piero della Franscesca

—avatar—

– Legend of the True Cross, Death of Adam (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

![]()

Barium Hydroxide could recover but not restore. Gaps remained (and remain).

The restoration carried out by Tintori in 1960-64 had declined to fill the cracks and gaps, the great lacunae, with anything other than monochrome plaster (lime, in fact, mixed with acrylics—bright, showy and compact); the directors of the new restoration elected to bridge them here and there with speculative but reversible watercolour overpainting—touch-ups which could be sponged away.

—great lacunae—

– Legend of the True Cross, Annunciation (detail, pre-restoration)

Piero della Franscesca

—speculative, reversible—

– Legend of the True Cross, Annunciation (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

What is generated on the wall of the chapel, then, is a hypothesis: a speculative assembly of elements and parts that is known to be new, but is thought to correlate better to the underlying truth of the matter (the original state of the object) than other more austere assemblies.

These assemblies are not only dictated by a desire to approximate the truth; they are also shaped by a need to preserve what remains. They represent a continual, if erratic, sometimes misguided, always provisional, making-good.

![]()

You do not merely recover, you recover from—from a trauma, a failing, an undermining. You navigate away, by a fixed star.

In the same way, an avatar is an avatar of something; it is not just a new random configuration, but conformable to a known pattern.

There is a fidelity at stake. You may have no stable and irreducible essence, but you have a system of memory, sub-routines of interest, enthusiasm, knowledge, appetite, which can, with imagination, regain if not their lustre then their place in a meaningful pattern.

I point, mentally, to Mrs Isobel Easter and her garden. I congratulate myself that this is now a healthy garden. It has been freed of its secret projects (the rain-garden guttering, the archaeological trench), and I have confined myself to restoring its health, clearing out here and there to let in light and air and water.

Mrs Isobel Easter, if not cured as such, is herself a thing now of water and air, not earth and fire. I like to think. Her sulphurous husband, one of the old gods bearing his scars, I am not so sure.

And Solomon. I will shortly wave Solomon off. He is leaving me in charge of his shop, his van. But he will be back at some point. He has not, after all, raised the true cross of himself from history.

In Piero's day, it is worth remembering, the true cross was a much-reduced, splintered object, held in cloisonné reliquaries in churches and monasteries across Europe and the near-east.

—reliquaries—

– Mosan Reliquary Cross

c.1160-1170

Or rather, there was no true cross, no pristine item indexed to our own submerged but incorruptible souls; only various degenerate ideas of it. That no object—ourselves included—actually stands outside history only complicates, does not invalidate, the attempt to locate them and arrange them to our satisfaction in the here-and-now.

![]()

If there is no true cross, then there is also no definitive recovery. Your days might be a straightforward if arrhythmic sequence of movement and paralysis, but which is which? Are you really well now? Or are you fatally winged and hurtling earthward, mistaking frictionless movement, freedom from pain, for freedom to move? it is impossible to tell, given that the future, on the shapeless brink of which we always hover, is dimensionless, unrelational.

—fatally winged—

– Legend of the True Cross, Dream of Constantine (detail)

Piero della Franscesca

No. You are never fully restored; you are only at best in restauro, a thing of scaffolding and tattered sheeting, of muttering specialist attention, of rigorously documented ills. How do you shore up or quarantine the persistent damage, the incurable spot? How do you accommodate the history? The chronic decline?

In 1469, Benozzo Gozzoli, chameleon of the quattrocento stylebook, was commissioned to fresco the external walls of the Camposanto in Pisa with scenes from the Old Testament. The work took him and his workshop fifteen years and on its completion the cycle numbered twenty-six frescoes.

But the frescoes, painted on external walls and exposed to the damp sea airs, were subject to immediate and relentless degradation. Gozzoli had prepared his arriccio, the first layer of plaster, on straw mats fixed to the walls; these mats ultimately absorbed moisture, corrupting the fresco from the inside.

And then, on the 27th of July 1944, the Camposanto was bombarded with allied incendiary shells, which set fire to the building and to the straw mats underlying the frescoes (where these had not already been shattered by the impact); the lead roof melted and dripped down over the walls.

What remains now of the frescoes? Almost nothing. There are some highly discoloured remnants, hard to read. There are some black and white photographs. There is a handful of preparatory sketches. A set of sinopie or underdrawings, which emerged after the shelling. And there is a sequence of engravings from the early years of the 19th century, when the frescoes were already in a terminal state of disrepair, which corrupt the style but document the narrative sequence and composition of the scenes.

From these scraps we can construct a complex mental object of a different order of being from the original frescoes: one that on the face of it is an intellectual, ascetic object, but which in fact brims over with information regarding its own fragility and our sense of loss. We built the frescoes of the Camposanto; we destroyed them; we preserve them. It is a cycle of diminishing, ever finer-grained amplitude.

—finer-grained amplitude—

– Tower of Babel, Camposanto

Benozzo Gozzoli

You will never function as you used to, as you used to hope you would. You have adapted to your relish for the world. But you can piece yourself together, collect yourself again and for the time being only; you can step out, again, into the sunlight of Pisa, Arezzo, Kochi, Norbiton.

You can have a coffee, read the paper, sit in the sun, think back over things; or amuse impressionable schoolchildren with the sight of some ancient scar, like a seafaring grandfather, laughing in his beard; some indulgent warty old god, who was never more than an avatar of an avatar, and who never had or cared to have much power anyway, painted anew and probably for the last time in new colours: cobalts, chromes, leads and cadmiums.

—painted anew—